Northern Territories Alcohol Labels Study

[1] The Association of Canadian Distillers, Beer Canada and the Canadian Vintners Association alleged that the Yukon government had no legislative authority to add the labels, and would be liable for defamation, defacement, damages (including damage to brands), and packaging trademark and copyright infringement, because the labels had been added without their consent.

[12] Erin Hobin of Public Health Ontario, a lead researcher on the study, praised the Yukon for its courage at the project launch.

[16] The Chief Medical Officer of Health said that, in the Yukon, alcohol use probably caused more harm than the use of any other substance,[25] and it had comparatively high rates of alcohol-related violence.

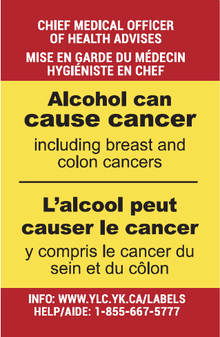

They designed the labels used in the study to have bright, attention-getting colours, clear messages, and a "large enough font size to be actually readable".

[11] Preparatory lab studies with local volunteers were used to choose the content for the labels,[29] so that they would contain the information consumers wanted to know.

[11] Yukon and the Northwest Territories (NWT) had both brought in mandatory small stick-on post-manufacturer labels in 1991, well before the study began (see images).

[8] The messages chosen by alcohol providers as part of voluntary warning label schemes tend to be unhelpful (they are thought to be unlikely to change knowledge, intentions, or behaviour).

[38] Broader awareness campaigns were planned to run during the study: in-store signage and handouts, a website, a toll-free helpline, and radio spots to augment the label messages.

[8] In this case, Beer Canada president Luke Harford wrote that "'Alcohol can cause cancer' is a false and misleading statement"[9] and said that it was "way too complex an issue to be discussed on the label".

[29][49] Westcott later said that the Association of Canadian Distillers was not denying that "excessive" drinking could cause "certain types" of cancer, but "We're just not sure that putting the word 'cancer' on a label is the most effective way to convey that information".

[53] The BC Craft Brewers Guild wrote to the vice-president of research at the University of Victoria, saying the labels bore "false, misleading and potentially dangerous information".

[49] In earlier online studies, exposure to similar labels made drinkers better at estimating how much they'd drunk and how much alcohol would exceed the reduced-risk limits.

[58] Industry lobbyists did not object to the NTAL study standard-drink labels as strongly as they did to the cancer warning, but they wanted to redesign them.

[11] The Association of Canadian Distillers, Beer Canada and the Canadian Vintners Association alleged that the Yukon government had no legislative authority to add the labels, and would be liable for defamation, defacement, damages (including damage to brands), and packaging trademark and copyright infringement, because the labels had been added without their consent.

[12] The minister said that they had had conversations around legislative authority, label placement, trademark infringement, and defamation, and "those terms leave us thinking that litigation is a real risk".

Researchers initially hoped that a third party might offer funding (or just advice and confidence) to allow the Yukon to fight a legal challenge,[58] as the Bloomberg Foundation did when Uruguay faced deeper-pocketed litigation over plain packaging for tobacco.

[65] Jacob Shelley, director of the health ethics, law and policy lab at the University of Western Ontario, agreed, and pointed out that manufacturers can make money by increasing alcohol consumption, an interest that conflicts with their legal duty to warn of its dangers.

[66] Solomon said that the provinces could also sue alcohol manufacturers for not warning, as they had previously sued tobacco companies, and a large class-action lawsuit was only a matter of time.

[40] The researchers also thought the alcohol industry, having actively intervened to conceal the health harms of their products from consumers, were opening themselves up to litigation for both the human suffering and recovery of healthcare costs.

[9] John Streicker, the minister responsible for the Yukon Liquor Corporation, appeared to blame the researchers for not consulting with industry, saying "One of the things to understand first and foremost is that this is a set of researchers that approached us to do a study here in the Yukon and the Northwest Territories and we agreed... We did encourage them to talk directly with the producers and largely I want to say, we left that in their hands".

[21] He thought that industry lobbyists would immediately have gone to all the relevant ministers, and threats would have been made, ending the study before it could get off the drawing board.

[36] He also argued that consultation would be unethical: "We don't want to compromise the accuracy of the information that is put out to consumers because the people who are making a profit from the product are concerned".

[7] He said it would be against research ethics guidelines to discuss warning label design with people who have vested commercial interests in increasing alcohol sales.

[48] An access to information request by freelance journalist James Wilt,[9] later published e-mail correspondence (see § External links, below) between the Liquor Corporation and some lobbyists (see sidebar).

They already know the conclusions they are going to present", citing the researchers' previous support for warning labels, and their opinions that its actions show that "the alcohol industry is itself a threat to public health".

The owner of the Yukon Shine Distillery, Karlo Krauzig, said he did not see why alcohol should have warning labels when other products that harm health do not, such as sugary beverages.

[46] The Irish Cancer Society and the Australian Foundation for Alcohol Research and Education said the NTAL study's halt would not stop their governments' plans to bring in mandatory warning labels.

[59]The Yukon's Chief Medical Officer of Health, Brendan Hanley, felt strongly about the issue, and expressed himself disappointed that the cancer warning had been removed.

[7][14] When the resumption of a reduced version of the study was announced, Tim Stockwell said that the "Alcohol can cause cancer" label was the most effective of the three, and eliminating it "diluted" the experiment.

[78][79] Governments bringing in alcohol warning labels face less expensive legal battles with industry if they have stronger evidence of public health benefits.