Norway Debate

One of the strongest critics of both appeasement and German aggression was Conservative backbencher Winston Churchill who, although he was one of the country's most prominent political figures, had last held government office in 1929.

Before the German invasion, he had pressed the Cabinet to ignore Norway's neutrality, mine its territorial waters and be prepared to seize Narvik, in both cases to disrupt the export of Swedish iron ore to Germany during winter months, when the Baltic Sea was frozen.

[4] When the House of Commons met on Thursday, 2 May, Labour leader Clement Attlee asked: "Is the Prime Minister now able to make a statement on the position in Norway?"

Some of Colville's colleagues including Lord Dunglass, who was Chamberlain's Parliamentary Private Secretary (PPS) at the time, considered the government position to be sound politically, but less so in other respects.

[14] He was eventually forced to defend the original usage of the phrase directly, claiming that he would have expected a German attack on the Allies at the outbreak of war when the difference in armed power was at its greatest.

The First Lord of the Admiralty has great abilities, but it is not fair to him that he should be put into an impossible position like that.Attlee struck a theme here that would recur throughout the debate – that the government was incompetent but not Churchill himself, even though he was part of it, as he had suffered from what Jenkins calls a misdirection of his talents.

Norwegians at Lillehammer for seven days held up with rifles only a German force with tanks, armoured cars, bombing aeroplanes and all the paraphernalia of modern war".

Wedgwood countered that with:[25][30] The British Navy could perfectly well defend this country if it had not gone to the other end of the Mediterranean to keep itself safe from bombing.Moments later, Admiral of the Fleet Sir Roger Keyes, the Conservative Member for Portsmouth North, arrived in the chamber and caused a stir because he was resplendent in his uniform with gold braid and six rows of medal ribbons.

If they had been more courageously and offensively employed they might have done much to prevent these unhappy happenings and much to influence unfriendly neutrals.As the House listened in silence, Keyes finished by quoting Horatio Nelson:[35] There are hundreds of young officers who are waiting eagerly to seize Warburton-Lee's torch, or emulate the deeds of Vian of the "Cossack".

One hundred and forty years ago, Nelson said, "I am of the opinion that the boldest measures are the safest" and that still holds good to-day.It was 19:30 when Keyes sat down to "thunderous applause".

Nicolson wrote that Keyes' speech was the most dramatic he had ever heard,[36] and the debate from that point on was no longer an investigation of the Norwegian campaign but "a criticism of the government's whole war effort".

He gave an analogy from his own experience which illustrated the government's lack of initiative:[42] I remember that many years ago in East Africa a young friend of mine went lion hunting.

That is in brief the story of our initiative over Norway.As tension increased in the House and Amery found himself speaking to a "crescendo of applause",[43] Edward Spears thought he was hurling huge stones at the government glasshouse with "the effect of a series of deafening explosions".

Some 300 years ago, when this House found that its troops were being beaten again and again by the dash and daring of the Cavaliers, by Prince Rupert's Cavalry, Oliver Cromwell spoke to John Hampden.

[47] It is generally understood that Labour did not intend a division before the debate began but Attlee, after hearing the speeches by Keyes and Amery, realised that discontent within Tory ranks was far deeper than they had thought.

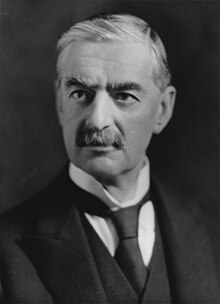

[56] Chamberlain appealed not for national unity but for the support of his friends in the House:[57] The words which the right honourable Gentleman has just uttered make it necessary for me to intervene for a moment or two at this stage.

All the more shame that we should have made fools of them.Emphasising the gravity of the situation, he argued that Britain was in the worst position strategically that it had ever been as a result of foreign policy failures, which he began to review from the 1938 Munich agreement onwards.

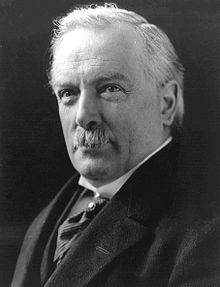

After dealing with some interruptions, Lloyd George criticised the rate of re-armament pre-war and to date:[64] Is there anyone in this House who will say that he is satisfied with the speed and efficiency of the preparations in any respect for air, for Army, yea, for Navy?

And here we are in the worst strategic position in which this country has ever been placed.Dealing with an intervention at this point, Lloyd George said, in passing, that he did not think that the First Lord was entirely responsible for all the things that happened in Norway.

Churchill intervened and said:[65] I take complete responsibility for everything that has been done by the Admiralty, and I take my full share of the burden.In answer, Lloyd George said:[66] The right honourable Gentleman must not allow himself to be converted into an air-raid shelter to keep the splinters from hitting his colleagues.Jenkins calls this "a brilliant metaphor" but wonders if it was spontaneous.

The Prime Minister is not in a position to make his personality in this respect inseparable from the interests of the country.Chamberlain stood and, leaning over the despatch box,[69] demanded:[70] What is the meaning of that observation?

On the contrary, I took pains to say that personalities ought to have no place in these matters.Lloyd George responded to that intervention with a direct call for Chamberlain to resign:[66] I was not here when the right honourable Gentleman made the observation, but he definitely appealed on a question which is a great national, imperial and world issue.

[67] On this occasion, he did present Churchill with some awkward questions about Norway but, as with other speakers before him, it was done with genuine respect amidst severe criticism of Chamberlain, Hoare, Simon and Stanley in particular.

If you dare, and forfeit is exacted, it is murder of our sailors; and if you are prudent, you are craven, cowardly, inept and timid.As for the lack of action at Trondheim, Churchill said it was not because of any perceived danger, but because it was thought unnecessary.

Instead, he attacked the government's critics by deploring what he called a cataract of unworthy suggestions and actual falsehoods during the last few days:[80] A picture has been drawn of craven politicians hampering their admirals and generals in their bold designs.

The Speaker would not rule on the matter and Churchill defiantly refused to withdraw the comment, adding that:[82] All day long we have had abuse, and now honourable members opposite will not even listen.Having defended the conduct of the naval operations in the Norwegian campaign at some length, Churchill now said little about the proposed vote, other than to complain about such short notice:[82] It seems to me that the House will be absolutely wrong to take such a grave decision in such a precipitate manner, and after such a little notice.He concluded by saying:[83] Let me say that I am not advocating controversy.

[87][88] Labour's Josiah Wedgwood led the singing of "Rule Britannia", joined by Conservative rebel Harold Macmillan of the Noes; that gave way to cries of "Go!"

Others were Nancy Astor, John Profumo, Quintin Hogg, Leslie Hore-Belisha and Edward Spears but not some expected dissidents such as Duncan Sandys, who abstained, and Brendan Bracken who, in Jenkins' words, "followed [Churchill's] example rather than his interest and voted with the government".

When Germany began its western offensive on the morning of 10 May, Chamberlain seriously considered staying on but, after receiving final confirmation from Labour that they required his resignation, he decided to stand down and advised the King to send for Churchill as his successor.

[95][96] The Norway debate is regarded as a high point in British parliamentary history, coming as it did at a time when Great Britain faced its gravest danger.