Norwegian Sea

[6] The present continental slope in the Norwegian Sea marks the border between Norway and Greenland as it stood approximately 250 million years ago.

Settling of the shelf after the separation of the continents has resulted in landslides, such as the Storegga Slide about 8,000 years ago that induced a major tsunami.

Large glaciers several kilometres high pushed into the land, forming fjords, removing the crust into the sea, and thereby extending the continental slopes.

[6] Deeper into the sea, there are two deep basins separated by a low ridge (its deepest point at 3,000 m) between the Vøring Plateau and Jan Mayen island.

[8] Four major water masses originating in the Atlantic and Arctic oceans meet in the Norwegian Sea, and the associated currents are of fundamental importance for the global climate.

Long-term measurements within the top 50 metres near the coast show a maximum temperature of 11.2 °C at the 63° N parallel in September and a minimum of 3.9 °C at the North Cape in March.

[21] In winter, the Norwegian Sea generally has the lowest air pressure in the entire Arctic and where most Icelandic Low depressions form.

[1] The Norwegian Sea is a transition zone between boreal and Arctic conditions, and thus contains flora and fauna characteristic of both climatic regions.

[24] Shrimp of the species Pandalus borealis play an important role in the diet of fish, particularly cod and blue whiting, and mostly occur at depths between 200 and 300 metres.

A special feature of the Norwegian Sea is extensive coral reefs of Lophelia pertusa, which provide shelter to various fish species.

Although these corals are widespread in many peripheral areas of the North Atlantic, they never reach such amounts and concentrations as at the Norwegian continental slopes.

[24] The Norwegian coastal waters are the most important spawning ground of the herring populations of the North Atlantic, and the hatching occurs in March.

Whereas a small herring population remains in the fjords and along the northern Norwegian coast, the majority spends the summer in the Barents Sea, where it feeds on the rich plankton.

[27][28] Blue whiting (Micromesistius poutassou) has benefited from the decline of the herring and capelin stocks as it assumed the role of major predator of plankton.

In the rest of the Norwegian Sea, it is found only during the reproduction season, at the Lofoten Islands,[25] whereas Pollachius virens and haddock spawn in the coastal waters.

[24] Significant numbers of minke, humpback, sei, and orca whales are present in the Norwegian Sea,[29] and white-beaked dolphins occur in the coastal waters.

Consequently, due to the Norwegian islands of Svalbard and Jan Mayen, the southeast, northeast and northwest edge of the sea fall within Norway.

[39] Two out of sixteen of the Total Allowed Catches (TACs) agreed upon by the European Union (EU) and Norway follow scientific advice.

As late as in 1845, the Encyclopædia metropolitana contained a multi-page review by Erik Pontoppidan (1698–1764) on ship-sinking sea monsters half a mile in size.

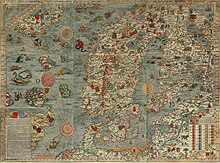

[45] Many legends might be based on the work Historia de gentibus septentrionalibus of 1539 by Olaus Magnus, which described the kraken and maelstroms of the Norwegian Sea.

[46] The kraken also appears in Alfred Tennyson's poem of the same name, in Herman Melville's Moby Dick, and in Twenty Thousand Leagues Under the Seas by Jules Verne.

It was described in the 13th century in the Old Norse Poetic Edda and remained an attractive subject for painters and writers, including Edgar Allan Poe, Walter Moers and Jules Verne.

[47] The Moskenstraumen is created as a result of a combination of several factors, including the tides, the position of the Lofoten, and the underwater topography; unlike most other whirlpools, it is located in the open sea rather than in a channel or bay.

With a diameter of 40–50 metres, it can be dangerous even in modern times to small fishing vessels that might be attracted by the abundant cod feeding on the microorganisms sucked in by the whirlpool.

[49] The first depth measurements of the Norwegian Sea were performed in 1773 by Constantine Phipps aboard HMS Racehorse, as a part of his North Pole expedition.

[51] The zoologist Georg Ossian Sars and meteorologist Henrik Mohn persuaded the government in 1874 to send out a scientific expedition, and between 1876 and 1878 they explored much of the sea aboard Vøringen.

[52] The data obtained allowed Mohn to establish the first dynamic model of ocean currents, which incorporated winds, pressure differences, sea water temperature, and salinity and agreed well with later measurements.

Since the late 19th century, the Norwegian Coastal Express sea line has been established, connecting the more densely populated south with the north of Norway by at least one trip a day.

This route was extensively used for supplies during World War II – of 811 US ships, 720 reached Russian ports, bringing some 4 million tonnes of cargo that included about 5,000 tanks and 7,000 aircraft.

[62] The large depth and harsh waters of the Norwegian Sea pose significant technical challenges for offshore drilling.