Notiomastodon

In the following years, the number of discovered fossils increased, which led Florentino Ameghino in 1889 to give the first general review of the proboscideans in his extensive work on the extinct mammals of Argentina.

In addition to the species already created by Cuvier and Fischer, Ameghino named some new ones, including "Mastodon" platensis, which he had already established a year earlier and whose description was based on a tusk fragment of an adult individual from San Nicolás de los Arroyos in the province of Buenos Aires, on the shores of the Paraná River, (catalog number MLP 8-63).

[11][12] In the northernmost part of South America, Juan Félix Proaño discovered in 1894 an almost complete skeleton near Quebrada Chalán, in the vicinity of Punín in the Ecuadorian province of Chimborazo.

[13] Only two years later Hoffstetter raised Haplomastodon to the level of the genus, and the main criterion for distinguishing it from Stegomastodon being the absence of a transverse opening in the atlas (first cervical vertebra).

The features of the transverse foramina of the first cervical vertebra, which Hoffstetter applied to distinguish Haplomastodon from Stegomastodon, turned out to be highly variable, even in the same individual, according to the investigations of Simpson and Paula Couto.

Other authors followed this idea and considered Haplomastodon chimborazi as the valid name (although in 2009 the taxon "Mastodon" waringi was preserved by the ICZN due to its multiple mentions in the scientific literature[18]).

[21] Only two years later, he published an exhaustive work focused on the anatomy of the skeleton of Haplomastodon, in which he clearly separated it from Stegomastodon and gave it an intermediate position between it and Cuvieronius in the Andes.

[14] Around the same period, Spencer George Lucas and collaborators reached a similar conclusion, especially after examining an almost complete skeleton of Stegomastodon from the Mexican state of Jalisco and determined that this genus should be separated from the South American gomphotheres due to its different musculoskeletal characteristics.

[25][26] This is the classification that has been adopted at various times in the following years, and Mothé and colleagues through extensive morphological analysis of the teeth and skeletons, found that Stegomastodon differed significantly from Notiomastodon and was confined to North America.

[31] Especially problematic is the genus Amahuacatherium, which was described in 1996 by Lidia Romero-Pittman based on a fragmented mandible and two isolated molars found in the Madre de Dios region of southeastern Peru.

This would make Amahuacatherium one of the first mammals to reach South America from the north before the Great American Biotic Interchange, which would only begin about six million years later.

[32] Additionally, this find is much older than the gomphotherid evidence considered as the oldest in both Central and South America, dating back to 7 and 2.5 million years, respectively.

These include, for example, a generally flatter skull, the formation of upper and lower fenders as well as molariform teeth with fewer ridges and a mamelonated masticatory surface pattern.

These include, for example, a generally flatter skull, the formation of upper and lower fenders as well as molariform teeth with fewer ridges and a mamelonated masticatory surface pattern.

[40] Gomphotherium Gnathabelodon Eubelodon Stegomastodon Sinomastodon Notiomastodon Rhynchotherium Cuvieronius Gomphotheres are first recorded at the end of the Oligocene in Africa and are among the first representatives of the proboscideans to leave that continent after the closure of the Tethys Ocean and the appearance of the land bridge to Eurasia during the transition to the Miocene.

[41] Some researchers have proposed the idea that Cuvieronius is a direct descendant of Rhynchotherium, as evidenced by its highly specialized upper tusks, which feature a spiral enamel band.

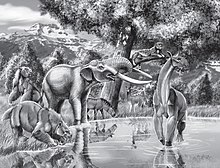

[50] This exchange occurred in both directions, so that for example ground sloths and glyptodonts arrived in the north, while carnivorous mammals and artiodactyls, as well as proboscideans, among others, mixed with the endemic fauna of the south.

[27] The oldest unambiguous evidence of Notiomastodon in South America is an individual tooth found on the continental shelf off the Brazilian coast in the state of Rio Grande do Sul, which was radiometrically dated to 464,000 years ago and therefore corresponds to the Middle Pleistocene.

Its distribution areas in central Chile may have been reached relatively late, either by a route from the Pampas to the low inter-Andean valleys or from the north through the Amazonian lowlands.

Due to the shortening of the skull at the snout, the eye orbit of Notiomastodon was above the front end of the molar tooth row, which is markedly more forward than in long-snouted gomphotheres such as Gomphotherium or Rhynchotherium.

The symphysis was typical of South American gomphotheres as it was relatively short (brevirostral), and in some individuals it pointed downwards and sometimes formed a small prominence, as is the case in Cuvieronius.

However, due to the different morphotypes, it more closely approximated the complex pattern of the chewing surface of Stegomastodon, which was formed mainly by the formation of additional lateral ridges.

This has also been delineated in studies on traces of wear and scratches on Notiomastodon molars from the Upper Pleistocene site of Aguas de Araxin Island in the Brazilian state of Minas Gerais.

Especially during the course of the Late Pleistocene, when climatic changes from the last glacial period in the Southern Cone caused forests to shrink and be replaced by grassland environments, this was an important adaptive phenomenon.

[77] A study of the tusk of a male animal from the Santiago de Chile basin allowed the analysis of the last four years of its life by means of isotope and thin-section analyses.

The reduced growth is interpreted to correspond to the musth stage, a hormone-controlled phase that occurs annually in modern elephants and is characterized by a huge increase in testosterone.

[10][16] Other finds are known from Brazil, where Notiomastodon was widely distributed from the open areas of the southern Chaco to the current Amazon basin, and fossil remains have been found on the continental shelf of the Atlantic coast.

[92][93] Large, mesoherbivorous mammals in the Brazilian Intertropical Region were widespread and diverse, including the cow-like toxodontids Toxodon platensis and Piauhytherium, the macraucheniid litoptern Xenorhinotherium and equids such as Hippidion principale and Equus neogaeus.

Xenarthran fossils are present in the area as well from several different families, like the giant megatheriid ground sloth Eremotherium, the fellow scelidotheriid Valgipes, the mylodontids Glossotherium, Ocnotherium, and Mylodonopsis.

[102] Some very recent finds of Notiomastodon are 11,740 to 11,100 years old and were obtained from Quereo in Chile, from Itaituba on the Tapajós River in central Brazil, and from Tibitó in Colombia, the latter being associated with three dozen tools of stone.