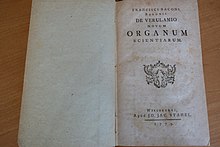

Novum Organum

The Novum Organum, fully Novum Organum, sive Indicia Vera de Interpretatione Naturae ("New organon, or true directions concerning the interpretation of nature") or Instaurationis Magnae, Pars II ("Part II of The Great Instauration"), is a philosophical work by Francis Bacon, written in Latin and published in 1620.

The title page of Novum Organum depicts a galleon passing between the mythical Pillars of Hercules that stand either side of the Strait of Gibraltar, marking the exit from the well-charted waters of the Mediterranean into the Atlantic Ocean.

Bacon hopes that empirical investigation will, similarly, smash the old scientific ideas and lead to greater understanding of the world and heavens.

Bacon's emphasis on the use of artificial experiments to provide additional observances of a phenomenon is one reason that he is often considered "the Father of the Experimental Philosophy" (for example famously by Voltaire).

[2] Importantly though, Bacon set the scene for science to develop various methodologies and ideologies, because he made the case against older Aristotelian approaches to science, arguing that method was needed because of the natural biases and weaknesses of the human mind, including the natural bias it has to seek metaphysical explanations which are not based on real observations.

Bacon begins the work with a rejection of pure a priori deduction as a means of discovering truth in natural philosophy.

The word instauration was intended to show that the state of human knowledge was to simultaneously press forward while also returning to that enjoyed by man before the Fall.

Bacon titled this first book Aphorismi de Interpretatione Naturae et Regno Hominis ("Aphorisms Concerning the Interpretation of Nature, and the Kingdom of Man").

The other way draws axioms from the sense and particulars by climbing steadily and by degrees so that it reaches the ones of highest generality last of all; and this is the true but still untrodden way.After many similar aphoristic reiterations of these important concepts, Bacon presents his famous Idols.

Now this comes either of his own unique and singular nature; or his education and association with others, or the books he reads and the several authorities of those whom he cultivates and admires, or the different impressions as they meet in the soul, be the soul possessed and prejudiced, or steady and settled, or the like; so that the human spirit (as it is allotted to particular individuals) is evidently a variable thing, all muddled, and so to speak a creature of chance..." (Aphorism 42).

These are "derived as if from the mutual agreement and association of the human race, which I call Idols of the Market on account of men's commerce and partnerships.

To these Bacon attaches an almost occult like power: But he who knows forms grasps the unity of nature beneath the surface of materials which are very unlike.

Through this comparative analysis, Bacon intends to eventually extrapolate the true form of heat, although it is clear that such a goal is only gradually approachable by degrees.

Indeed, the hypothesis that is derived from this eliminative induction, which Bacon names The First Vintage, is only the starting point from which additional empirical evidence and experimental analysis can refine our conception of a formal cause.

Bacon described numerous classes of Instances with Special Powers, cases in which the phenomenon one is attempting to explain is particularly relevant.

They are "labour-saving devices or shortcuts intended to accelerate or make more rigorous the search for forms by providing logical reinforcement to induction.

As mentioned above, this second book of Novum organum was far from complete and indeed was only a small part of a massive, also unfinished work, the Instauratio magna.

Two over-lapping movements developed; "one was rational and theoretical in approach and was headed by Rene Descartes; the other was practical and empirical and was led by Francis Bacon.

An interesting characteristic of Bacon's apparently scientific tract was that, although he amassed an overwhelming body of empirical data, he did not make any original discoveries.

Bacon never claimed to have brilliantly revealed new unshakable truths about nature—in fact, he believed that such an endeavour is not the work of single minds but that of whole generations by gradual degrees toward reliable knowledge.

In many ways, Bacon's contribution to the advancement of human knowledge lies not in the fruit of his scientific research but in the reinterpretation of the methods of natural philosophy.

Where else in the literature before Bacon does one come across a stripped-down natural-historical programme of such enormous scope and scrupulous precision, and designed to serve as the basis for a complete reconstruction of human knowledge which would generate new, vastly productive sciences through a form of eliminative induction supported by various other procedures including deduction?

Where else does one find a concept of scientific research which implies an institutional framework of such proportions that it required generations of permanent state funding to sustain it?