Nuclear shell model

The model was developed in 1949 following independent work by several physicists, most notably Maria Goeppert Mayer and J. Hans D. Jensen, who received the 1963 Nobel Prize in Physics for their contributions to this model, and Eugene Wigner, who received the Nobel Prize alongside them for his earlier groundlaying work on the atomic nuclei.

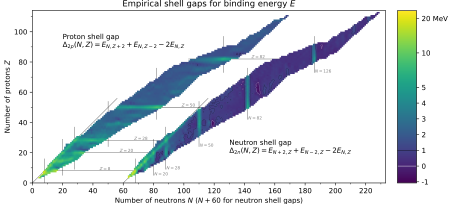

Due to variations in orbital filling, the upper magic numbers are 126 and, speculatively, 184 for neutrons, but only 114 for protons, playing a role in the search for the so-called island of stability.

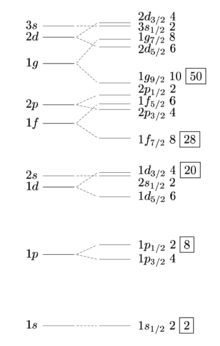

[3] To get these numbers, the nuclear shell model starts with an average potential with a shape somewhere between the square well and the harmonic oscillator.

The magic numbers of nuclei, as well as other properties, can be arrived at by approximating the model with a three-dimensional harmonic oscillator plus a spin–orbit interaction.

This would give, for example, in the first three levels ("ℓ" is the angular momentum quantum number): Nuclei are built by adding protons and neutrons.

This means that the magic numbers are expected to be those in which all occupied shells are full.

First, we have to describe the system by the quantum numbers j, mj and parity instead of ℓ, ml and ms, as in the hydrogen–like atom.

Due to the spin–orbit interaction, the energies of states of the same level but with different j will no longer be identical.

For example, consider the states at level 4: The harmonic oscillator potential

One main consequence is that the average radius of nucleons' orbits would be larger in a realistic potential.

Both effects lead to a reduction in the energy levels of high ℓ orbits.

Another way to predict magic (and semi-magic) numbers is by laying out the idealized filling order (with spin–orbit splitting but energy levels not overlapping).

Taking the leftmost and rightmost total counts within sequences bounded by / here gives the magic and semi-magic numbers.

This means that the spin (i.e. angular momentum) of the nucleus, as well as its parity, are fully determined by that of the ninth neutron.

This 4th d-shell has a j = 5/2, thus the nucleus of 178O is expected to have positive parity and total angular momentum 5/2, which indeed it has.

For nuclei farther from the magic quantum numbers one must add the assumption that due to the relation between the strong nuclear force and total angular momentum, protons or neutrons with the same n tend to form pairs of opposite angular momentum.

The ordering of angular momentum levels within each shell is according to the principles described above – due to spin–orbit interaction, with high angular momentum states having their energies shifted downwards due to the deformation of the potential (i.e. moving from a harmonic oscillator potential to a more realistic one).

This is due to the relation between angular momentum and the strong nuclear force.

The nuclear magnetic moment of neutrons and protons is partly predicted by this simple version of the shell model.

The electric dipole of a nucleus is always zero, because its ground state has a definite parity.

Higher electric and magnetic multipole moments cannot be predicted by this simple version of the shell model for reasons similar to those in the case of deuterium.

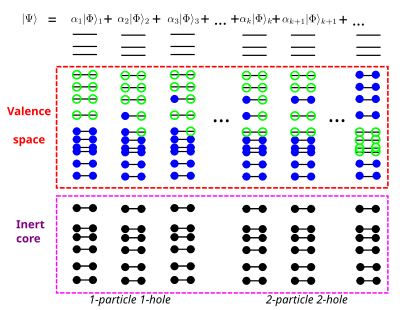

This residual term comes from the part of the inter-nucleon interaction not included in the approximative average potential.

The Schrödinger equation is solved on this basis, using an effective Hamiltonian specifically suited for the model space.

This Hamiltonian is different from the one of free nucleons as, among other things, it has to compensate for excluded configurations.

This forms the basis of the no-core shell model, which is an ab initio method.

It is necessary to include a three-body interaction in such calculations to achieve agreement with experiments.

Quantum mechanically, it is impossible to have a collective rotation of a sphere, so this implied that the shape of these nuclei was non-spherical.

For these reasons, Aage Bohr, Ben Mottelson, and Sven Gösta Nilsson constructed models in which the potential was deformed into an ellipsoidal shape.

Usually the angular frequency vector ω is taken to be perpendicular to the symmetry axis, although tilted-axis cranking can also be considered.

Igal Talmi developed a method to obtain the information from experimental data and use it to calculate and predict energies which have not been measured.