Nullification crisis

In Washington, an open split on the issue occurred between Jackson and Vice President John C. Calhoun, a native South Carolinian and the most effective proponent of the constitutional theory of state nullification.

Rather than suggesting individual, although concerted, measures of this sort, Kentucky was content to ask its sisters to unite in declarations that the acts were "void and of no force", and in "requesting their appeal" at the succeeding session of the Congress.

[16] Madison biographer Ralph Ketcham wrote: Though Madison agreed entirely with the specific condemnation of the Alien and Sedition Acts, with the concept of the limited delegated power of the general government, and even with the proposition that laws contrary to the Constitution were illegal, he drew back from the declaration that each state legislature had the power to act within its borders against the authority of the general government to oppose laws the legislature deemed unconstitutional.

Ten state legislatures with heavy Federalist majorities from around the country censured Kentucky and Virginia for usurping powers that supposedly belonged to the federal judiciary.

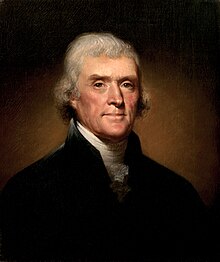

[18]The election of 1800 was a turning point in national politics, as the Federalists were replaced by the Democratic-Republican Party led by Jefferson, but the four presidential terms spanning the period from 1800 to 1817 "did little to advance the cause of states' rights and much to weaken it."

A boom in American manufacturing during the prolonged cessation of trade with Britain created an entirely new class of enterprisers, most of them tied politically to the Republicans, who might not survive without tariff protection.

However in 1819, the nation suffered its first financial panic and the 1820s turned out to be a decade of political turmoil that again led to fierce debates over competing views of the exact nature of American federalism.

The "extreme democratic and agrarian rhetoric" that had been so effective in 1798 led to renewed attacks on the "numerous market-oriented enterprises, particularly banks, corporations, creditors, and absentee landholders".

[28] The Tariff of 1828 was largely the work of Martin Van Buren (although Silas Wright Jr. of New York prepared the main provisions) and was partly a political ploy to elect Andrew Jackson President.

[29] As expected, Jackson and his running mate John Calhoun carried the entire South with overwhelming numbers in every state but Louisiana, where Adams drew 47% of the vote in a losing effort.

Nationalists such as Calhoun were forced by the increasing power of such leaders to retreat from their previous positions and adopt, in the words of Ellis, "an even more extreme version of the states' rights doctrine" in order to maintain political significance within South Carolina.

[40] Fearful that "hotheads" such as McDuffie might force the legislature into taking drastic action against the federal government, historian John Niven describes Calhoun's political purpose in the document: All through that hot and humid summer, emotions among the vociferous planter population had been worked up to a near-frenzy of excitement.

The whole tenor of the argument built up in the "Exposition" was aimed to present the case in a cool, considered manner that would dampen any drastic moves yet would set in motion the machinery for repeal of the tariff act.

[43]Rhett's rhetoric about revolution and war was too radical in the summer of 1828 but, with the election of Jackson assured, James Hamilton Jr. on October 28 in the Colleton County Courthouse in Walterborough "launched the formal nullification campaign.

With silence no longer an acceptable alternative, Calhoun looked for the opportunity to take control of the antitariff faction in the state; by June he was preparing what would be known as his Fort Hill Address.

The truth can no longer be disguised, that the peculiar institution of the Southern States and the consequent direction which that and her soil have given to her industry, has placed them in regard to taxation and appropriations in opposite relation to the majority of the Union, against the danger of which, if there be no protective power in the reserved rights of the states they must in the end be forced to rebel, or, submit to have their paramount interests sacrificed, their domestic institutions subordinated by Colonization and other schemes, and themselves and children reduced to wretchedness.

Unlike state political organizations in the past, which were led by the South Carolina planter aristocracy, this group appealed to all segments of the population, including non-slaveholder farmers, small slaveholders, and the Charleston non-agricultural class.

And even should she stand ALONE in this great struggle for constitutional liberty ... that there will not be found, in the wider limits of the state, one recreant son who will not fly to the rescue, and be ready to lay down his life in her defense.

In December 1831, with the proponents of nullification in South Carolina gaining momentum, Jackson recommended "the exercise of that spirit of concession and conciliation which has distinguished the friends of our Union in all great emergencies.

The leading proponents[58] of the nationalistic view included Daniel Webster, Supreme Court Justice Joseph Story, Judge William Alexander Duer, John Quincy Adams, Nathaniel Chipman, and Nathan Dane.

While Calhoun's "Exposition" claimed that nullification was based on the reasoning behind the Kentucky and Virginia Resolutions, an aging James Madison in an August 28, 1830, letter to Edward Everett, intended for publication, disagreed.

This issue was featured at the December 1831 National Republican convention in Baltimore, which nominated Clay for president, and the proposal to recharter was formally introduced into Congress on January 6, 1832.

Jackson kept lines of communication open with unionists such as Joel Poinsett, William Drayton, and James L. Petigru and sent George Breathitt, brother of the Kentucky governor, to independently obtain political and military intelligence.

[71] His intent regarding nullification, as communicated to Van Buren, was "to pass it barely in review, as a mere buble [sic], view the existing laws as competent to check and put it down."

But should this reasonable reliance on the moderation and good sense of all portions of our fellow citizens be disappointed, it is believed that the laws themselves are fully adequate to the suppression of such attempts as may be immediately made.

[74] The Force bill went to the Senate Judiciary Committee, chaired by Pennsylvania protectionist William Wilkins and supported by members Daniel Webster and Theodore Frelinghuysen of New Jersey; it gave Jackson everything he asked.

In his February 25 speech ending the debate on the tariff, Clay captured the spirit of the voices for compromise by condemning Jackson's Proclamation to South Carolina as inflammatory, admitting the same problem with the Force Bill, but indicating its necessity, and praising the Compromise Tariff as the final measure to restore balance, promote the rule of law, and avoid the "sacked cities", "desolated fields", and "smoking ruins" he said the failure to reach a final accord would produce.

With both parties arguing who could best defend Southern institutions, the nuances of the differences between free soil and abolitionism, which became an issue in the late 1840s with the Mexican War and territorial expansion, never became part of the political dialogue.

[89] Describing the legacy of the crisis, Sean Wilentz writes: The battle between Jacksonian democratic nationalists, northern and southern, and nullifier sectionalists would resound through the politics of slavery and antislavery for decades to come.

Historian Charles Edward Cauthen writes: Probably to a greater extent than in any other Southern state South Carolina had been prepared by her leaders over a period of thirty years for the issues of 1860.