O'Shaughnessy Dam (California)

[6] The dam and reservoir are the source for the Hetch Hetchy Aqueduct, which provides water for over two million people in San Francisco and other municipalities of the west Bay Area.

Deriving from a largely wild and pristine area of the Sierra Nevada, the Hetch Hetchy supply is some of the cleanest municipal water in the US, requiring only primary filtration and disinfection.

Preservationist groups such as the Sierra Club lobby for the restoration of the valley, while others argue that leaving the dam in place would be the better economic and environmental decision.

[11] In the late 19th century, the city of San Francisco was rapidly outgrowing its limited water supply, which depended on intermittent local springs and streams.

[14] Although Phelan managed to secure water rights for the Tuolumne River in 1901,[15] his appeals to the federal government for development of the Hetch Hetchy Valley were unsuccessful.

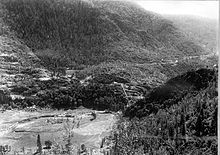

However, since 1890, Hetch Hetchy Valley and the surrounding lands had been part of Yosemite National Park and thus off-limits to utility development, let alone at the grand scale proposed by the city.

[19] Led by naturalist and mountaineer John Muir, the Sierra Club adamantly opposed the city of San Francisco as it sought permission from the federal government to build a dam in the valley.

[26] However, on December 24, 1914, with construction on the dam barely underway, Muir died, leaving his Sierra Club to fight a protracted battle against the Hetch Hetchy Project over the next ten years.

"[27] The Sierra Club argued that it was not necessary for San Francisco to destroy the valley for its water supply, pointing out the availability of other sites with reasonable proximity[28] – including the Mokelumne River, which the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers reported in 1913 as "a better and cheaper source than Hetch Hetchy".

To transport workers and materials, the city hired Frederick Rolandi, a San Francisco engineer who had previous experience designing railways, to oversee construction the Hetch Hetchy Railroad.

[20] A retaining wall was poured on the upstream side to prevent water seepage into the foundation hole, and the granite was scoured and artificially roughened to prepare for receiving concrete.

[36] The concrete for the dam was processed in a plant located shortly upstream from the construction site, with sand and rock excavated from abundant alluvial deposits in the Hetch Hetchy valley.

[36] This was mixed with cement shipped in on the Hetch Hetchy Railroad and local boulders ranging from 1 ft (0.30 m) to several yards (metres) in diameter to produce a cyclopean construction material for the dam.

[4] Kirkwood is serviced with a hydraulic head of 1,450 feet (440 m) through the Canyon Tunnel, and produces an annual average of 549 million kilowatt hours (KWh).

Moccasin generates 427 million KWh per year, and is fed by Hetch Hetchy water through the Mountain Tunnel,[5] which provides a maximum head of 1,300 feet (400 m).

[51] Because of the unique geology of the Hetch Hetchy watershed, which consists of shallow soils underlain by solid granite bedrock, water that flows into the reservoir is exceptionally clear and of very high quality.

The report strove to ensure that all solutions must be technologically feasible and affordable and must assure a dependable supply of water to both San Francisco and all affected California communities.

Opponents of dam removal state that the estimated demolition cost of $3–10 billion[46] is a poor investment,[62][63] especially in regards of the resulting loss of renewable hydroelectric power, which would have to be replaced by polluting fossil fuel generation.

[69] Despite the hotly contested status of O'Shaughnessy Dam in the environmental field, and occasional federal money set aside for studying alternatives to Hetch Hetchy – such as $7 million provided by President George W. Bush in 2007 in the National Park Service budget[70] – local support for its removal is relatively low.

In 2012, San Francisco voters rejected Proposition F, which would have ordered the city to study the removal of O'Shaughnessy Dam and draft a plan to replace Hetch Hetchy water, by a vote of 77 percent against.

[71] Proposition F would have allocated $8 million to create a feasibility study by 2016; new water delivery and filtration systems would have to be in place by 2025 and Hetch Hetchy Reservoir would have to be drained by 2035.