O-Train

[3] The O-Train network is fully grade separated and accessible, featuring low-floor trams and trains that allow for easy boarding.

The diesel-powered Talents would have been replaced with electric trams more suitable for on-street operation in the downtown area, specifically the Siemens S70 Avanto (due to the "design, build, and maintain" contracting process which has focused upon the bid proposing this vehicle).

[9] Other bids had proposed the Bombardier Flexity Swift and a Kinki Sharyo tram.With the use of electric power, greater frequency, and street-level running in central Ottawa, the expanded system would have borne much more resemblance to the urban tramways usually referred to by the phrase "light rail" than does the pilot project (though the use of the Capital Railway track and additional existing tracks which have been acquired along its route may cause it to remain a mainline railway for legal purposes).

Terry Kilrea, who finished second to Chiarelli in the 2003 municipal election and briefly ran for mayor in 2006, believed the plan was vastly too expensive and would also be a safety hazard for Ottawa drivers.

Mayoral candidate Alex Munter supported light rail but argued that the plan would do little to meet Ottawa's transit needs and that the true final expense of the project had been kept secret.

Larry O'Brien, a businessman who entered the race late, wanted to postpone the project for six months before making a final decision.

[10] City transportation staff, though long in favour of bus rapid transit systems, disagreed with Jeanes's assessment.

It started a debate on the issue during the week of December 4 with three options including the status quo, the truncation of portions of the current track or the cancellation of the contract.

An Ottawa Sun article had reported on December 5 that if the project were cancelled, there could be lawsuits by Siemens against the city totalling as much as $1 billion.

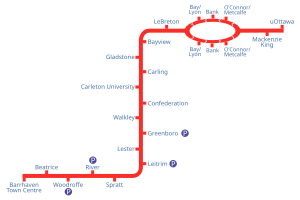

[14] The new mayor, Larry O'Brien, opted to keep the extension to Barrhaven while eliminating the portion that would run from Lebreton Flats to the University of Ottawa.

However, Council also introduced the possibility of building several tunnels in the downtown core in replacement of rail lines on Albert and Slater.

With the presence of Rainer Bloess, who was absent during the previous vote,[17] the council decided to cancel the project by a margin of 13-11 despite the possibility of lawsuits from Siemens, the contract holder.

A poll conducted by the mayor's office showed that a majority of south-end residents disagreed with the cancellation of the project but only a third wanted to revive it.

[21] The city also committed funds to perform an environmental assessment for an east–west route, running between Kanata and Orleans mainly via an existing railway right-of-way bypassing downtown.

Planners initially explored the possibility of using the system's three Talents for an east–west pilot project after they were to be replaced by electric trams on the north–south line.

[citation needed] Service to Gatineau would also be possible to serve commuters, as there is a railway bridge over the Ottawa River nearby, but the government of Gatineau was until 2016 opposed to extending the Trillium Line into its territory; Ottawa's city staff have taken steps to isolate the north–south line from the bridge,[22] so it would need to be re-built north of Bayview station.

The committee, headed by the former member of parliament and cabinet minister David Collenette, recommended that Ottawa's needs would be best served by light rail through the future.

[24] On March 3, 2008, the city of Ottawa revealed four different options for its transit expansion plan, and presented at Open House consultation meetings during the same week.

[27] The plan was passed by the city council with a vote of 19–4 and included motions for possible rail extensions to the suburbs depending on population density and available funding.

[28] However, Kitchissippi Ward councillor Christine Leadman expressed concerns of the environment integrity impacts of light-rail along the Kichi Zibi Mikan which is situated on NCC land.

[31] In early September 2008, city staff suggested that the first phase of the transit plan to be built would be similar to Option 3 with rail service from Riverside South to Blair Station via a downtown tunnel, the construction of a by-pass transit corridor via the General Hospital and a streetcar circuit along Carling Avenue, although Alex Cullen mentioned that Council already rejected the option of streetcars running on that road.

[34] On March 6, 2019, the Ottawa city council voted 19–3 to approve the C$4.66 billion contracts to begin construction of the Stage 2 plan.

The O-Train could potentially become a connection point with the proposed Gatineau LRT system, to be run by the STO, which is planned to operate partly on the Ottawa side of the river.

[46] The surface option on Wellington also includes the possibility of creating a future transit loop by having the LRT cross back into Gatineau via the Alexandra Bridge.