O-type star

These stars illuminate any surrounding material and are largely responsible for the distinct bluish-white and pink coloration of a galaxy's arms.

At O2–O4, the distinction between main sequence and supergiant stars is narrow, and may not even represent true luminosity or evolutionary differences.

At intermediate O5–O8 classes, the distinction between "O((f))" main sequence, "O(f)" giants, and "Of" supergiants is well-defined and represents a definite increase in luminosity.

[3] Star types O3 to O8 are classified as luminosity class sub-type "Vz" if they have a particularly strong 468.6 nm ionised helium line.

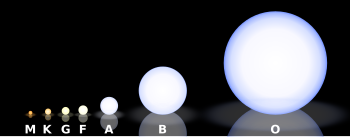

They have characteristic surface temperatures ranging from 30,000–52,000 K, emit intense ultraviolet ('actinic') light, and so appear in the visible spectrum as bluish-white.

This mixing of core material into the upper layers is often enhanced by fast rotation, and has a dramatic effect on the evolution of O-type stars.

Although they have a wide range of distinct characteristics, it is not fully understood how they all form and develop; they are thought to have degenerate cores that will eventually be exposed as a white dwarf.

Before then the material outside that core is mostly helium with a thin layer of hydrogen, which is rapidly being lost due to the strong stellar wind.

[16] In the lifecycle of O-type stars, different metallicities and rotation rates introduce considerable variation in their evolution, but the basics remain the same.

[8] O-type stars start to move slowly from the zero-age main sequence almost immediately after they form, gradually becoming cooler and slightly more luminous.

Although they may be characterised spectroscopically as giants or supergiants, they continue to burn hydrogen in their cores for several million years and develop in a very different manner from low-mass stars such as the Sun.

If they do not explode as a supernova first, they will then lose their outer layers and become hotter again, sometimes going through a number of blue loops before finally reaching the Wolf–Rayet stage.

At certain masses or chemical makeups, or perhaps as a result of binary interactions, some of these lower-mass stars become unusually hot during the horizontal branch or AGB phases.

There may be multiple reasons, not fully understood, including stellar mergers or very late thermal pulses re-igniting post-AGB stars.

O-type stars are rare but luminous, so they are easy to detect and there are a number of naked eye examples.

Also, as these stars have shorter lifetimes, they cannot move great distances before their death and so they stay in or relatively near to the spiral arm in which they formed.

On the other hand, less massive stars live longer and thus are found throughout the galactic disc, including in between the spiral arms.

O-type stars emit copious amounts of ultraviolet radiation, which ionizes the gas in the cloud and pushes it away.

[18] O-type stars explode as supernovae when they die, releasing vast amounts of energy, contributing to the disruption of a molecular cloud.

[19] These effects disperse the remaining molecular material in a star-forming region, ultimately stopping the birth of new stars, and possibly leaving behind a young open cluster.