Ocean deoxygenation

Firstly, it occurs in coastal zones where eutrophication has driven some quite rapid (in a few decades) declines in oxygen to very low levels.

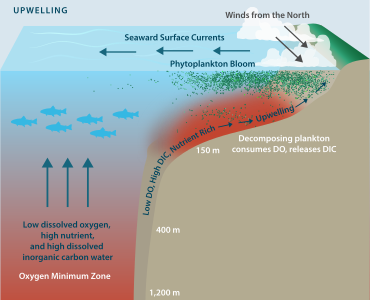

They are natural phenomena that result from respiration of sinking organic material produced in the surface ocean.

In many of these areas, this decline does not mean these low oxygen regions become uninhabitable for fish and other marine life but over many decades may do, particularly in the Pacific and Indian Ocean.

While oxygen minimum zones (OMZs) occur naturally, they can be exacerbated by human impacts like climate change and land-based pollution from agriculture and sewage.

[26] Research has attempted to model potential changes to OMZs as a result of rising global temperatures and human impact.

[29][28][30] Existing Earth system models project considerable reductions in oxygen and other physical-chemical variables in the ocean due to climate change, with potential ramifications for ecosystems and humans.

The global decrease in oceanic oxygen content is statistically significant and emerging beyond the envelope of natural fluctuations.

[31][24] The rate and total content of oxygen loss varies by region, with the North Pacific emerging as a particular hotspot of deoxygenation due to the increased amount of time since its deep waters were last ventilated (see thermohaline circulation) and related high apparent oxygen utilization (AOU).

[11] The results from mathematical models show that global ocean oxygen loss rates will continue to accelerate up to 125 T mol year−1 by 2100 due to persistent warming, a reduction in ventilation of deeper waters, increased biological oxygen demand, and the associated expansion of OMZs into shallower areas.

[25] These areas are called oxygen minimum zones (OMZs), and there is a wide variety of open ocean systems that experience these naturally low oxygen conditions, such as upwelling zones, deep basins of enclosed seas, and the cores of some mode-water eddies.

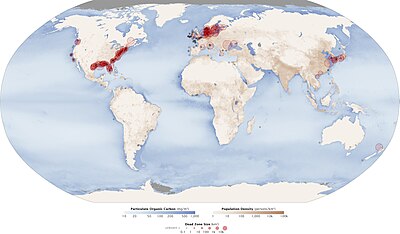

Since 1950, more than 500 sites in coastal waters have reported oxygen concentrations below 2 mg liter−1, which is generally accepted as the threshold of hypoxic conditions.

[28][30][32] Oxygen-poor waters of coastal and open ocean systems have largely been studied in isolation of each other, with researchers focusing on eutrophication-induced hypoxia in coastal waters and naturally occurring (without apparent direct input of anthropogenic nutrients) open ocean OMZs.

[39] The lower limit of OMZs is associated with the reduction in biological oxygen consumption, as the majority of organic matter is consumed and respired in the top 1,000 m of the vertical water column.

Hypoxic conditions in coastal systems like the Gulf of Mexico are usually tied to discharges of rivers, thermohaline stratification of the water column, wind-driven forcing, and continental shelf circulation patterns.

[44] Areas that have not previously experienced low oxygen conditions, like the coastal shelf of Oregon on the West coast of the United States, have recently and abruptly developed seasonal hypoxia.

[7][46][8][9] As low oxygen zones expand vertically nearer to the surface, they can affect coastal upwelling systems such as the California Current on the coast of Oregon (US).

As the ocean warms, mixing between water layers decreases, resulting in less oxygen and nutrients being available for marine life.

[49] Short term effects can be seen in acutely fatal circumstances, but other sublethal consequences can include impaired reproductive ability, reduced growth, and increase in diseased population.

If the water an organism's regular habitat sits in has oxygen concentrations lower than it can tolerate, it will not want to live there anymore.

[28][53] A fish's behavior in response to ocean deoxygenation is based upon their tolerance to oxygen poor conditions.

Species with low anoxic tolerance tend to undergo habitat compression in response to the expansion of OMZs.

Some species of billfish, predatory pelagic predators such as sailfish and marlin, that have undergone habitat compression actually have increased growth since their prey, smaller pelagic fish, experienced the same habitat compression, resulting in increased prey vulnerability to billfishes.

[55] Fish with tolerance to anoxic conditions, such as jumbo squid and lanternfish, can remain active in anoxic environments at a reduced level, which can improve their survival by increasing avoidance of anoxia intolerant predators and have increased access to resources that their anoxia intolerant competitors cannot.

[56][57] The relationship between zooplankton and low oxygen zones is complex and varies by species and life stage.

[60] The movements of zooplankton as a result of ocean deoxygenation can affect fisheries, global nitrogen cycling, and trophic relationships.