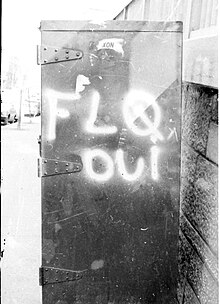

October Crisis

The premier of Quebec, Robert Bourassa, and the mayor of Montreal, Jean Drapeau, supported Trudeau's invocation of the War Measures Act, which limited civil liberties and granted the police far-reaching powers, allowing them to arrest and detain 497 people.

[2] While mailboxes, particularly in the affluent and predominantly Anglophone city of Westmount, were common targets, the largest single bombing occurred at the Montreal Stock Exchange on February 13, 1969, which caused extensive damage and injured 27 people.

Other targets included Montreal City Hall, Royal Canadian Mounted Police, the T. Eaton Company department store,[3] armed forces recruiting offices, railway tracks, statues,[4][5] and army installations.

On July 24, 1967, the nationalist cause received support from French President Charles de Gaulle who, standing on a balcony in Montreal, shouted "Vive le Québec libre".

On February 26, 1970, two men in a panel truck, including Jacques Lanctôt, were arrested in Montreal when they were found with a sawed-off shotgun and a communiqué announcing the kidnapping of the Israeli consul.

In June, police raided a home in the small community of Prévost, located north of Montreal in the Laurentian Mountains, and found firearms, ammunition, 140 kilograms (300 lb) of dynamite, detonators, and the draft of a ransom note to be used in the kidnapping of the United States consul.

Three days later, on October 16, the Cabinet, under Trudeau's chairmanship, advised the governor general to invoke the War Measures Act at the request of the Premier of Quebec, Robert Bourassa; and the Mayor of Montreal, Jean Drapeau.

In total, 497 people were arrested, including union activist Michel Chartrand,[26] singer Pauline Julien and her partner, future Quebec Minister Gérald Godin, poet Gaston Miron, Dr. Henri Bellemare, simple living advocate Serge Mongeau, and CBC journalist Nick Auf der Maur and a junior producer.

[28]: 103 [non-primary source needed] Since then, the government's use of the War Measures Act in peacetime has been a subject of debate in Canada as it gave police sweeping powers of arrest and detention.

[31] The Royal 22e Régiment, more commonly known as the "Van Doos", the most famous French-Canadian regiment in the Canadian Army, was deployed to Montreal to guard buildings.

The combination of the increased powers of arrest granted by the War Measures Act, and the military deployment requisitioned and controlled by Quebec's government gave every appearance that martial law had been imposed.

Trudeau's target was not two frightened little bands of terrorists, one of which soon strangled its helpless victim: it was the affluent dilettantes of revolutionary violence, cheering on the anonymous heroes of the FLQ.

The proclamation of the War Measures Act and the thousands of grim troops pouring into Montreal froze the cheers, dispersed the coffee-table revolutionaries, and left them frightened and isolated while the police rounded up suspects whose offence, if any, was dreaming of blood in the streets".

[32]: 257 Pierre Laporte was eventually found killed by his captors, while James Cross was freed after 59 days as a result of negotiations with the kidnappers who requested exile to Cuba rather than facing trial in Quebec.

[37] A few critics (most notably Tommy Douglas and some members of the New Democratic Party)[38] believed that Trudeau was excessive in advising the use of the War Measures Act to suspend civil liberties and that the precedent set by this incident was dangerous.

However, in its Manifesto the FLQ stated: "In the coming year (Quebec Premier Robert) Bourassa will have to face reality; 100,000 revolutionary workers, armed and organized.

"[40] Given this declaration, seven years of bombings, and communiques throughout that time that strove to present an image of a powerful organization spread secretly throughout all sectors of society, the authorities took significant action.

On April 3, 1969, Trudeau announced that Canada would stay in NATO after all, but he drastically cut military spending and pulled out half of the 10,000 Canadian soldiers and airmen stationed in West Germany.

[32]: 255 In early 1970 the government introduced a white paper Defence in the Seventies, which stated the "Priority One" of the Canadian Forces would be upholding internal security rather than preparing for World War III, which of course meant a sharp cut in military spending since the future enemy was now envisioned to be the FLQ rather than the Red Army.