Octopus

Octopuses inhabit various regions of the ocean, including coral reefs, pelagic waters, and the seabed; some live in the intertidal zone and others at abyssal depths.

Strategies to defend themselves against predators include the expulsion of ink, the use of camouflage and threat displays, the ability to jet quickly through the water and hide, and even deceit.

[25] The octopus has an elongated body that is bilaterally symmetrical along its dorso-ventral (back to belly) axis; the head and foot are on the ventral side but act as the anterior (front) of the animal.

[27] Lacking skeletal support, the arms work as muscular hydrostats and contain longitudinal, transverse and circular muscles around a central axial nerve.

Basal species, the Cirrina, have stout gelatinous bodies with webbing that reaches near the tip of their arms, and two large fins above the eyes, supported by an internal shell.

The tract consists of a crop, where the food is stored; a stomach, where it is smushed with other gut material; a caecum where the now sludgy food is separated into particles and liquids and which also absorbs fats; the digestive gland, where liver cells break down and absorb the fluid and become "brown bodies"; and the intestine, where the built-up waste is turned into faecal ropes by secretions and ejected out of the funnel via the rectum.

Before reaching the branchial heart, each branch of the vena cava expands to form renal appendages which are in direct contact with the thin-walled nephridium.

[59][60] The giant nerve fibers of the cephalopod mantle have been widely used for many years as experimental material in neurophysiology; their large diameter (due to lack of myelination) makes them relatively easy to study compared with other animals.

[65] Attached to the brain are two organs called statocysts (sac-like structures containing a mineralised mass and sensitive hairs), that allow the octopus to sense the orientation of its body.

[72][73] When octopuses reproduce, the male uses a specialised arm called a hectocotylus to transfer spermatophores (packets of sperm) from the terminal organ of the reproductive tract (the cephalopod "penis") into the female's mantle cavity.

[26] About forty days after mating, the female giant Pacific octopus attaches strings of small fertilised eggs (10,000 to 70,000 in total) to rocks in a crevice or under an overhang.

[76]: 74–75 In the argonaut (paper nautilus), the female secretes a fine, fluted, papery shell in which the eggs are deposited and in which she also resides while floating in mid-ocean.

[82] Experimental removal of both optic glands after spawning was found to result in the cessation of broodiness, the resumption of feeding, increased growth, and greatly extended lifespans.

[97][96] It used to be thought that the hole was drilled by the radula, but it has now been shown that minute teeth at the tip of the salivary papilla are involved, and an enzyme in the toxic saliva is used to dissolve the calcium carbonate of the shell.

[37] In the deep-sea genus Stauroteuthis, some of the muscle cells that control the suckers in most species have been replaced with photophores which are believed to fool prey by directing them to the mouth, making them one of the few bioluminescent octopuses.

Jetting is used to escape from danger, but is physiologically inefficient, requiring a mantle pressure so high as to stop the heart from beating, resulting in a progressive oxygen deficit.

[118] Octopuses typically hide or disguise themselves by camouflage and mimicry; some have conspicuous warning coloration (aposematism) or deimatic behaviour (“bluffing” a seemingly threatening appearance).

[118] The blue rings of the highly venomous blue-ringed octopus are hidden in muscular skin folds which contract when the animal is threatened, exposing the iridescent warning.

[119] The Atlantic white-spotted octopus (Callistoctopus macropus) turns bright brownish red with oval white spots all over in a high contrast display.

Octopuses have an innate immune system; their haemocytes respond to infection by phagocytosis, encapsulation, infiltration, or cytotoxic activities to destroy or isolate the pathogens.

[130] The scientific name Octopoda was first coined and given as the order of octopuses in 1818 by English biologist William Elford Leach,[131] who classified them as Octopoida the previous year.

In turn, the coleoids (including the squids and octopods) brought their shells inside the body and some 276 million years ago, during the Permian, split into the Vampyropoda and the Decabrachia.

The molecular analysis of the octopods shows that the suborder Cirrina (Cirromorphida) and the superfamily Argonautoidea are paraphyletic and are broken up; these names are shown in quotation marks and italics on the cladogram.

Cirroteuthidae Stauroteuthidae Opisthoteuthidae Cirroctopodidae Tremoctopodidae Alloposidae Argonautidae Ocythoidae Eledonidae Bathypolypodidae Enteroctopodidae Octopodidae Megaleledonidae Bolitaenidae Amphitretidae Vitreledonellidae Octopuses, like other coleoid cephalopods but unlike more basal cephalopods or other molluscs, are capable of greater RNA editing, changing the nucleic acid sequence of the primary transcript of RNA molecules, than any other organisms.

For example, a stone carving found in the archaeological recovery from Bronze Age Minoan Crete at Knossos (1900–1100 BC) depicts a fisherman carrying an octopus.

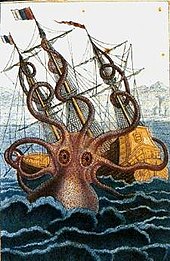

[151] A battle with an octopus plays a significant role in Victor Hugo's 1866 book Travailleurs de la mer (Toilers of the Sea).

[152] Ian Fleming's 1966 short story collection Octopussy and The Living Daylights, and the 1983 James Bond film were partly inspired by Hugo's book.

[156] The biologist P. Z. Myers noted in his science blog, Pharyngula, that octopuses appear in "extraordinary" graphic illustrations involving women, tentacles, and bare breasts.

[167] Methods to capture octopuses include pots, traps, trawls, snares, drift fishing, spearing, hooking and hand collection.

[181] Their problem-solving skills, along with their mobility and lack of rigid structure enable them to escape from supposedly secure tanks in laboratories and public aquariums.