Minoan civilization

Subsequent research has shown that they served a variety of religious and economic purposes rather than being royal residences, though their exact role in Minoan society is a matter of continuing debate.

The modern term "Minoan" is derived from the name of the mythical King Minos, who the Classical Greeks believed to have ruled Knossos in the distant past.

An alternative system, proposed by Greek archaeologist Nikolaos Platon, divides Minoan history into four periods termed Prepalatial, Protopalatial, Neopalatial, and Postpalatial.

For example, Minoan artifacts from the LM IB period have been found in 18th Dynasty contexts in Egypt, for which Egyptian chronology provides calendar dates.

[17] A comparative study of DNA haplogroups of modern Cretan men showed that a male founder group, from Anatolia or the Levant, is shared with the Greeks.

Continuing a trend that began during the Neolithic, settlements grew in size and complexity, and spread from fertile plains towards highland sites and islands as the Minoans learned to exploit less hospitable terrain.

Many of the most recognizable Minoan artifacts date from this time, for instance the snake goddess figurines, La Parisienne Fresco, and the marine style of pottery decoration.

The post-eruption LM IB period (c.1625-1470) saw ambitious new building projects, booming international trade, and artistic developments such as the marine style.

Similarly, while some researchers have attempted to link them to lingering environmental disruption from the Thera eruption, others have argued that the two events are too distant in time for any causal relation.

The language of administration shifted to Mycenaean Greek and material culture shows increased mainland influence, reflecting the rise of a Greek-speaking elite.

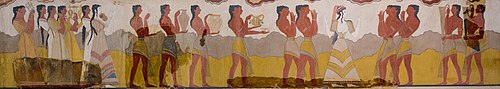

Sinclair Hood described an "essential quality of the finest Minoan art, the ability to create an atmosphere of movement and life although following a set of highly formal conventions".

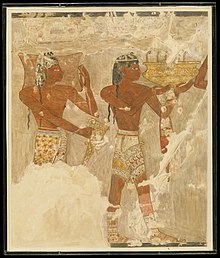

While Minoan figures, whether human or animal, have a great sense of life and movement, they are often not very accurate, and the species is sometimes impossible to identify; by comparison with Ancient Egyptian art they are often more vivid, but less naturalistic.

[57] The seascapes surrounding some scenes of fish and of boats, and in the Ship Procession miniature fresco from Akrotiri, land with a settlement as well, give a wider landscape than is usual.

However, while many of the artistic motifs are similar in the Early Minoan period, there are many differences that appear in the reproduction of these techniques throughout the island which represent a variety of shifts in taste as well as in power structures.

[61] Minoan jewellery has mostly been recovered from graves, and until the later periods much of it consists of diadems and ornaments for women's hair, though there are also the universal types of rings, bracelets, armlets and necklaces, and many thin pieces that were sewn onto clothing.

These have long thin scenes running along the centre of the blade, which show the violence typical of the art of Mycenaean Greece, as well as a sophistication in both technique and figurative imagery that is startlingly original in a Greek context.

[72] The archaeological record suggests that mostly cup-type forms were created in precious metals,[73] but the corpus of bronze vessels was diverse, including cauldrons, pans, hydrias, bowls, pitchers, basins, cups, ladles and lamps.

Minoan-manufactured goods suggest a network of trade with mainland Greece (notably Mycenae), Cyprus, Syria, Anatolia, Egypt, Mesopotamia and westward as far as the Iberian Peninsula.

[89] While historians and archaeologists have long been skeptical of an outright matriarchy, the predominance of female figures in authoritative roles over male ones seems to indicate that Minoan society was matriarchal, and among the most well-supported examples known.

[91] It is now used as a general term for ancient pre-monetary cultures where much of the economy revolved around the collection of crops and other goods by centralized government or religious institutions (the two tending to go together) for redistribution to the population.

This is still accepted as an important part of the Minoan economy; all the palaces have very large amounts of space that seems to have been used for storage of agricultural produce, some remains of which have been excavated after they were buried by disasters.

Recent scholarly opinion sees a much more diverse religious landscape although the absence of texts, or even readable relevant inscriptions, leaves the picture very cloudy.

The mythical creature called the Minoan Genius is somewhat threatening but perhaps a protective figure, possibly of children; it seems to largely derive from Taweret the Egyptian hybrid crocodile and hippopotamus goddess.

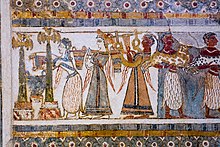

Men with a special role as priests or priest-kings are identifiable by diagonal bands on their long robes, and carrying over their shoulder a ritual "axe-sceptre" with a rounded blade.

Minoan sacred symbols include the bull (and its horns of consecration), the labrys (double-headed axe), the pillar, the serpent, the sun-disc, the tree, and even the Ankh.

Juktas considered a temple; an EMII sanctuary complex at Fournou Korifi in south-central Crete, and in an LMIB building known as the North House in Knossos.

[147] On mainland Greece during the shaft-grave era at Mycenae, there is little evidence for major Mycenaean fortifications; the citadels follow the destruction of nearly all neopalatial Cretan sites.

[full citation needed] Lucia Nixon wrote: We may have been over-influenced by the lack of what we might think of as solid fortifications to assess the archaeological evidence properly.

Warfare such as there was in the southern Aegean early Bronze Age was either personalized and perhaps ritualized (in Crete) or small-scale, intermittent and essentially an economic activity (in the Cyclades and the Argolid/Attica).

[162] A 2013 archaeogenetics study by Hughey at al. published in Nature Communications compared skeletal mtDNA from ancient Minoan skeletons that were sealed in a cave in the Lasithi Plateau between 3,700 and 4,400 years ago to 135 samples from Greece, Anatolia, western and northern Europe, North Africa and Egypt.