Odaenathus

The circumstances surrounding his rise are ambiguous; he became the lord (ras) of the city, a position created for him, as early as the 240s and by 258, he was styled a consularis, indicating a high status in the Roman Empire.

Odaenathus remained on the side of Rome; assuming the title of king, he led the Palmyrene army, attacking the Persians before they could cross the Euphrates to the eastern bank, inflicting a considerable defeat.

In 266, he launched a second invasion of Persia but had to abandon the campaign and head north to Bithynia to repel the attacks of Germanic raiders besieging the city of Heraclea Pontica.

[19][24] The fifth-century historian Zosimus asserted that Odaenathus descended from "illustrious forebears",[note 5][20] but the position of the family in Palmyra is debated; it was probably part of the wealthy mercantile class.

[note 6][17] The historians Franz Altheim and Ruth Stiehl suggested that Odaenathus was part of a new elite of Bedouins driven from their home east of the Euphrates by the aggressive Sassanian dynasty after 220.

[55][56][57] For most of its existence, the Palmyrene army was decentralized under the command of several generals,[58] but the rise of the Sassanian Empire in 224, and its incursions, which affected Palmyrene trade,[59] combined with the weakness of the Roman Empire, probably prompted the Palmyrene council to elect a lord for the city in order for him to lead a strengthened army:[29][58][60] The Roman emperor, Gordian III, died in 244 during a campaign against Persia and this might have been the event which led to the election of a lord for Palmyra to defend it: Odaenathus,[61] whose elevation, according to the historian Udo Hartmann, can be explained by Odaenathus probably being a successful military or caravan commander, and his descent from one of the most influential families in the city.

[note 11][65] The ras title enabled the bearer to effectively deal with the Sassanid threat, in that it probably vested in him supreme civil and military authority;[note 12][58] an undated inscription refers to Odaenathus as a ras and records the gift of a throne to him by a Palmyrene citizen named "Ogeilu son of Maqqai Haddudan Hadda", which confirms the supreme character of Odaenathus' title.

[71][72] During the second campaign of the invasion, Shapur I conquered Antioch on the Orontes, the traditional capital of Syria,[73] and headed south, where his advance was checked in 253 by a noble from Emesa, Uranius Antoninus.

[78] The sixth-century historian Peter the Patrician wrote that Odaenathus approached Shapur I to negotiate Palmyrene interests but was rebuffed and the gifts sent to the Persians were thrown into the river.

[63][75] Several inscriptions dating to the end of 257 or early 258 show Odaenathus bearing the Greek title ὁ λαμπρότατος ὑπατικός (ho lamprótatos hupatikós; Latin: clarissimus consularis).

The Septimian colony of Tyre" were found inscribed on a marble base;[83][84] the inscription is not dated and if it was made after 257 then it indicates that Odaenathus was appointed as the governor of the province.

[110][111][112] Perhaps driven by a desire to take revenge for the destruction of Palmyrene trade centers and to discourage Shapur I from initiating future attacks, Odaenathus launched an offensive against the Persians.

[113] The suppression of Fulvius Macrianus' rebellion probably prompted Gallienus to entrust the Palmyrene monarch with the war in Persia and Roman soldiers were in the ranks of Odaenathus' army for this campaign.

[115] A little later he destroyed the Jewish city of Nehardea, 45 kilometres (28 mi) west of the Persian capital Ctesiphon,[note 21][118] as he considered the Jews of Mesopotamia to be loyal to Shapur I.

[126][127] A statue was erected and dedicated for Herodianus to celebrate his coronation by Septimius Worod, the duumviri (magistrate) of Palmyra, and Julius Aurelius, the Queen's procurator (treasurer).

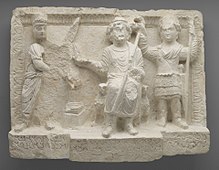

[136] Odaenathus' son was crowned with a diadem and a tiara; the choice of Antioch on the Orontes was probably meant to demonstrate that the Palmyrene monarchs were now the successors of the Seleucid and Iranian rulers who had controlled Syria and Mesopotamia in the past.

[127] In analyzing the rise of Odaenathus and his complicated relationship with Rome, the historian Gary K. Young concluded that "to search for any kind of regularity or normality in such a situation is clearly pointless".

In Rome, broad power delegation by the Emperor to an individual from outside the imperial family was not considered a problem;[140] such authority had been granted several times since the days of Augustus in the first century.

[141] The Syrian perspective was different:[140] according to Potter, the dedication celebrating Herodianus' coronation on the Orontes should be interpreted to mean a "Palmyrene claim to kingship in Syria" and control over it during the reign of Odaenathus.

[143] Such different understandings eventually led to the conflict between Rome and Palmyra during the reign of Zenobia, who considered her husband's Roman offices hereditary and an expression of independent authority.

[150] In parallel to the Iranian practice of making the government a family enterprise, Odaenathus bestowed his own gentilicium (Septimius) upon his leading generals and officials such as Zabdas, Zabbai and Worod.

[note 29][159] Another writer in the Palmyrene court, Nicostratus of Trebizond, probably accompanied the King on his campaigns and wrote a history of the period, starting with Philip the Arab and ending shortly before Odaenathus' death.

The tribes attacking Anatolia were probably the Heruli who built ships to cross the Black Sea in 267 and ravaged the coasts of Bithynia and Pontus, besieging Heraclea Pontica.

[176] The historian Nathanael Andrade, noting that since the Augustan History, Zosimus, Zonaras, and Syncellus all refer to a family feud or a domestic conspiracy in their writings, they must have been recounting an early tradition regarding the assassination.

[189] The mint of Antioch on the Orontes ceased the production of Gallienus' coins in early 268, and while this could be related to fiscal troubles, it could also have been ordered by Zenobia in retaliation for the murder of her husband.

[190] Andrade proposed that the assassination was the result of a coup conducted by Palmyrene notables in collaboration with the imperial court whose officials were dissatisfied with Odaenathus' autonomy.

According to Gianluca Serra, the conservation zoologist based in Palmyra at the time of the panel's discovery, the tigers are Panthera tigris virgata, once common in the region of Hyrcania in Iran.

[228] The King was praised by Libanius,[229] and the fourth-century writer of the Augustan History, while placing Odaenathus among the Thirty Tyrants (probably because he assumed the title of king, in the view of the eighteenth-century historian Edward Gibbon),[230] speaks highly of his role in the Persian War and credits him with saving the empire: "Had not Odaenathus, prince of the Palmyrenes, seized the imperial power after the capture of Valerian when the strength of the Roman state was exhausted, all would have been lost in the East".

Everywhere victorious, he liberated the cities and the territories belonging to each of them and made the enemies place their salvation in their prayers rather than in the force of arms.The successes of Odaenathus are treated sceptically by a number of modern scholars.

[245] Other scholars, such as Jacob Neusner, noted that while the accounts of the 260 engagement might be an exaggeration, Odaenathus did become a real threat to Persia when he regained the cities formerly taken by Shapur I and besieged Ctesiphon.