Portraits of Odaenathus

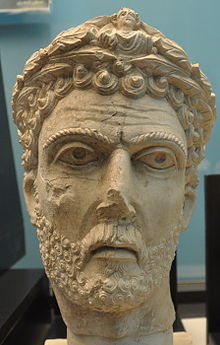

Odaenathus, the king of Palmyra from 260 to 267 CE, has been identified by modern scholars as the subject of sculptures, seal impressions, and mosaic pieces.

Odaenathus besieged the Sasanian capital Ctesiphon in 263, and although the city did not fall, the campaign led to a full restoration of Roman provinces taken by Shapur I.

Generally, the criteria for determining whether a piece represents the king are its material (imported marble, in contrast to local limestone) and iconography, such as the presence of royal attributes (crowns or diadems).

[10][11][9] Odaenathus was assassinated alongside Herodianus in 267 while campaigning against Germanic raiders in Heraclea Pontica, a city in Bithynia;[12] the perpetrator and motives are unclear.

[16] A few small clay tesserae were found in Palmyra with impressions of the king and his name,[17] but no large-scale portrait has been confirmed through inscriptions (limiting knowledge of Odaenathus' appearance).

[15] In general, Palmyrene sculptures are rudimentary portraits; although individuality was not abandoned, most pieces exhibit little difference among figures of a similar age and gender.

[26] The Danish rabbi and scholar David Jakob Simonsen proposed that the Copenhagen head was part of a console statue of a Palmyrene who was honoured by the city.

[28] The archaeologist Valentin Müller, based on the Copenhagen head's moving posture, forehead, and a characteristic fold between the nose and mouth, proposed that it was sculpted during the time of Emperor Decius (reigned 249–251).

[35] The archaeologist Klaus Parlasca rejected Ingholt's hypothesis regarding the honorary function of the portraits, and considered the two heads fragments of a funeral kline (sarcophagus lid).

[21] The archaeologist Jean-Charles Balty noted the relative incompleteness of the rear of both portraits and the thickness of the necks, indicating that the heads were not intended to be seen in profile.

[37] The archaeologist Eugenia Equini Schneider agreed with Simonsen and Ingholt that the heads had an honorary function,[21] but (based on their iconography) dated them to the late second or early third century.

[41] Gawlikowski suggested that the heads depicted three men from the same family, and considered that their excavation from a tomb, and their remarkable resemblance to the portraits in Copenhagen and Istanbul, confirm that the latter two were also funerary, and not honorary, objects.

[note 5][47] The piece was tentatively identified as depicting the king by the archaeologist Johannes Kollwitz,[49] but Parlasca considered it a fragment of a funeral kline.

[54] Due to the resemblance of the Benaki head to the portraits at the Copenhagen and Istanbul museums, the archaeologist Stavros Vlizos proposed that the man belonged to the family of Odaenathus.

[19] Gawlikowski, agreeing with Parlasca, maintained that most of the oversized limestone heads with thick necks were connected to funeral practices such as sarcophagus lids;[19] this includes the portraits from the hexagonal tomb and the Copenhagen and Istanbul museums.

[57] Its face was polished with care; the turban has a rippled surface, partly treated with a gradine (toothed chisel) to accentuate the difference between the fabric headdress and the strands of the hair.

A Palmyrene lead token in the National Museum of Damascus has a profile of Odaenathus' son and co-King of Kings, Herodianus, who is beardless and wearing a high conical tiara adorned with a crescent.

The diadem was probably linked in a Greek context to the god Dionysus, who played a part in royal ideology as a victorious leader,[67] and the headdress became a symbol of monarchy in the East.

On one side, a man's head is shown; covering all the available surface, he has a heavily built face, a full beard, and thick hair or a headdress (probably the lion-skin dress of Heracles).

[17] Tesserae are made by pressing a gem into clay; such seals, portraying royals without inscription, can be issued only in the name of the person depicted.

If Heracles is depicted, this was meant to glorify the monarch's victory over Persia; the tessera could have been a ticket to the coronation of Odaenathus and his son, Herodianus.

[74] This tessera, also in the National Museum of Damascus, depicts a king in a tiara on one side; a ball of hair in chignon style is attached to the back of the head.

Gawlikowski concluded that Herodianus is depicted with a tiara and Odaenathus, in the same bearded portrait as RTP 4 with the diadem and earring, must have appeared on the worn-out side.

According to Gianluca Serra (a conservation zoologist based in Palmyra at the time of the panel's discovery), both are Caspian tigers, which were once common in the region of Hyrcania in Iran.

[note 7] The text is Palmyrene cursive and probably the signature of the artist, but the many errors in writing and its incongruous position raise the possibility that it is a secondary addition which attempted to replace an original inscription.

In the Palmyra mosaic, Bellerophon is distinguished from his representation in Europe; instead of being heroically nude, he is dressed in the same manner as the rider in the tiger-hunt scene: pants, tunic, and a kandys.

The costume is known Parthian court attire, recognizable in the paintings of the synagogue of Doura-Europos depicting important figures such as the pharaoh in the Book of Exodus.

[86] The shape of the helmet has no parallel in contemporary military use, Persian or Roman; it is reminiscent of rare Hellenistic samples from Pergamon, a style adopted in Palmyra for war deities such as Arsu.

[88] Gawlikowski proposed that Odaenathus is depicted as Bellerophon, and the Chimera (who fits the description of Shapur I as a great beast in the thirteenth Sibylline Oracle) is a representation of the Persians.

[89] A wall painting from the temple of Artemis Azzanathkona in Dura-Europos depicts a Roman soldier offering a sacrifice to a deity with a Palmyrene mounted figure to the far left.