Odesa

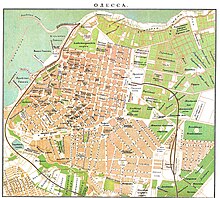

Odesa[a] (also spelled Odessa)[b] is the third most populous city and municipality in Ukraine and a major seaport and transport hub located in the south-west of the country, on the northwestern shore of the Black Sea.

In the Middle Ages successive rulers of the Odesa region included various nomadic tribes (Petchenegs, Cumans), the Golden Horde, the Crimean Khanate, the Grand Duchy of Lithuania, and the Ottoman Empire.

Russia formally gained possession of the Sanjak of Özi (Ochakiv Oblast)[40] as a result of the Treaty of Jassy (Iaşi)[37] in 1792 and it became a part of Yekaterinoslav Viceroyalty.

The Russian Empire took full control of Crimea, as well as land between the Southern Bug and the Dniester, including the Khadzhibey Estuary where the Turkish fortress of Khadjibey was located.

[41] On permission of the Archbishop of Yekaterinoslav Amvrosiy, the Black Sea Kosh Host, that was located around the area between Bender and Ochakiv, built second after Sucleia wooden church of Saint Nicholas.

Nearby stood the military barracks and the country houses (dacha) of the city's wealthy residents, including that of the Duc de Richelieu, appointed by Tsar Alexander I as Governor of Odesa in 1803.

[46][47] Dismissive of any attempt to forge a compromise between quarantine requirements and free trade, Prince Kuriakin (the Saint Petersburg-based High Commissioner for Sanitation) countermanded Richelieu's orders.

Richelieu founded Odessa – watched over it with paternal care – labored with a fertile brain and a wise understanding for its best interests – spent his fortune freely to the same end – endowed it with a sound prosperity, and one which will yet make it one of the great cities of the Old World".

Odesa became home to an extremely diverse population of Albanians, Armenians, Azeris, Bulgarians, Crimean Tatars, Frenchmen, Germans (including Mennonites), Greeks, Italians, Jews, Poles, Romanians, Russians, Turks, Ukrainians, and traders representing many other nationalities (hence numerous "ethnic" names on the city's map, for example Frantsuzky (French) and Italiansky (Italian) Boulevards, Grecheskaya (Greek), Yevreyskaya (Jewish), Arnautskaya (Albanian) Streets).

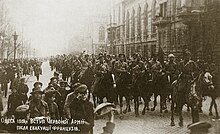

The Ukrainian general Nykyfor Hryhoriv who sided with Bolsheviks managed to drive the Triple Entente forces out of the city, but Odesa was soon retaken by the Russian White Army.

[62] After the Nazi forces began to lose ground on the Eastern Front, the Romanian administration changed its policy, refusing to deport the remaining Jewish population to extermination camps in German occupied Poland, and allowing Jews to work as hired labourers.

Domestic migration of the Odesan middle and upper classes to Moscow and Leningrad, cities that offered even greater opportunities for career advancement, also occurred on a large scale.

Despite this, the city grew rapidly by filling the void of those left with new migrants from rural Ukraine and industrial professionals invited from all over the Soviet Union.

Flora is of the deciduous variety and Odesa is known for its tree-lined avenues which, in the late 19th and early 20th centuries, made the city a favourite year-round retreat for the Russian aristocracy.

[citation needed] Due to the effects of climate and weather on sedimentary rocks beneath the city, the result is instability under some buildings' foundations.

During the tsarist era, Odesa's climate was considered to be beneficial for the body, and thus many wealthy but sickly persons were sent to the city in order to relax and recuperate.

Typically, for a total of 4 months – from June to September – the average sea temperature in the Gulf of Odesa and the city's bay area exceeds 20 °C (68 °F).

[83] The city typically experiences dry, cold winters which are relatively mild when compared to most of Ukraine, as they are marked by temperatures that rarely fall below −10 °C (14 °F).

Odesa Oblast is also home to many different nationalities and minority ethnic groups, including Albanians, Armenians, Azeris, Crimean Tatars, Bulgarians, Georgians, Greeks, Jews, Poles, Roma, Romanians, Turks, among others.

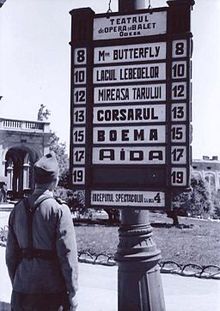

In 1887 one of the city's most well known architectural monuments was completed – the theatre, which still hosts a range of performances to this day; it is widely regarded as one of the world's finest opera houses.

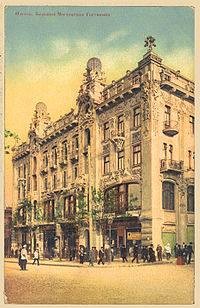

Derybasivska Street, an attractive pedestrian avenue named after José de Ribas, the Neapolitan-born founder of Odesa and decorated Russian Navy Admiral from the Russo-Turkish War, is famous by its unique character and architecture.

[citation needed] During the summer it is common to find large crowds of people leisurely sitting and talking on the outdoor terraces of numerous cafés, bars and restaurants, or simply enjoying a walk along the cobblestone street, which is not open to vehicular traffic and is kept shaded by the linden trees which line its route.

[citation needed] In addition to all the state-run universities mentioned above, Odesa is also home to many private educational institutes and academies which offer highly specified courses in a range of different subjects.

The Italian writer, Slavist and anti-fascist dissident Leone Ginzburg was born in Odesa into a Jewish family, and then went to Italy where he grew up and lived.

[citation needed] These qualities are reflected in the "Odesa dialect", which borrows chiefly from the characteristic speech of the Odesan Jews, and is enriched by a plethora of influences common for the port city.

The Odesan Jew in the jokes always "came out clean" and was, in the end, a lovable character – unlike some of other jocular nation stereotypes such as The Chukcha, The Ukrainian, The Estonian or The American.

Odesa is linked to the Ukrainian capital, Kyiv, by the M05 Highway, a high quality multi-lane road which is set to be re-designated, after further reconstructive works, as an 'Avtomagistral' (motorway) in the near future.

The M14 is of particular importance to Odesa's maritime and shipbuilding industries as it links the city with Ukraine's other large deep water port Mariupol which is located in the south east of the country.

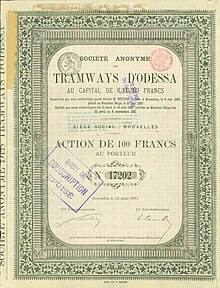

[citation needed] The city's public transit system is currently made up of trams,[154] trolleybuses, buses and fixed-route taxis (marshrutkas).

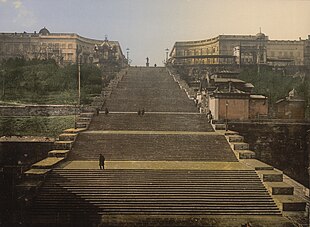

[156] One additional mode of transport in Odesa is the Potemkin Stairs funicular railway, which runs between the city's Primorsky Bulvar and the sea terminal, has been in service since 1902.