Oganesson

In December 2015, it was recognized as one of four new elements by the Joint Working Party of the international scientific bodies IUPAC and IUPAP.

[15][16] The name honors the nuclear physicist Yuri Oganessian, who played a leading role in the discovery of the heaviest elements in the periodic table.

Because of relativistic effects, theoretical studies predict that it would be a solid at room temperature, and significantly reactive,[3][17] unlike the other members of group 18 (the noble gases).

[29] The definition by the IUPAC/IUPAP Joint Working Party (JWP) states that a chemical element can only be recognized as discovered if a nucleus of it has not decayed within 10−14 seconds.

This value was chosen as an estimate of how long it takes a nucleus to acquire electrons and thus display its chemical properties.

Danish chemist Hans Peter Jørgen Julius Thomsen predicted in April 1895, the year after the discovery of argon, that there was a whole series of chemically inert gases similar to argon that would bridge the halogen and alkali metal groups: he expected that the seventh of this series would end a 32-element period which contained thorium and uranium and have an atomic weight of 292, close to the 294 now known for the first and only confirmed isotope of oganesson.

[11] It was 107 years from Thomsen's prediction before oganesson was successfully synthesized, although its chemical properties have not been investigated to determine if it behaves as the heavier congener of radon.

[63] In a 1975 article, American chemist Kenneth Pitzer suggested that element 118 should be a gas or volatile liquid due to relativistic effects.

This contradicted predictions that the cross sections for reactions with lead or bismuth targets would go down exponentially as the atomic number of the resulting elements increased.

[65] In 1999, researchers at Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory made use of these predictions and announced the discovery of elements 118 and 116, in a paper published in Physical Review Letters,[66] and very soon after the results were reported in Science.

[68] In June 2002, the director of the lab announced that the original claim of the discovery of these two elements had been based on data fabricated by principal author Victor Ninov.

Headed by Yuri Oganessian, a Russian nuclear physicist of Armenian ethnicity, the team included American scientists from the Lawrence Livermore National Laboratory in California.

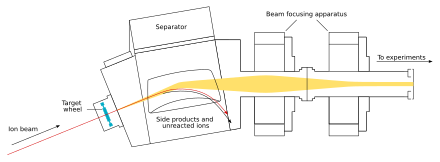

[13] On 9 October 2006, the researchers announced[13] that they had indirectly detected a total of three (possibly four) nuclei of oganesson-294 (one or two in 2002[74] and two more in 2005) produced via collisions of californium-249 atoms and calcium-48 ions.

[75][76][77][78][79] In 2011, IUPAC evaluated the 2006 results of the Dubna–Livermore collaboration and concluded: "The three events reported for the Z = 118 isotope have very good internal redundancy but with no anchor to known nuclei do not satisfy the criteria for discovery".

[81] Nevertheless, researchers were highly confident that the results were not a false positive, since the chance that the detections were random events was estimated to be less than one part in 100000.

[83] This was on account of two 2009 and 2010 confirmations of the properties of the granddaughter of 294Og, 286Fl, at the Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory, as well as the observation of another consistent decay chain of 294Og by the Dubna group in 2012.

The experiment was then halted, as the glue from the sector frames covered the target and blocked evaporation residues from escaping to the detectors.

[85][86][87] A search beginning in summer 2016 at RIKEN for 295Og in the 3n channel of this reaction was unsuccessful, though the study is planned to resume; a detailed analysis and cross section limit were not provided.

[88][89] Using Mendeleev's nomenclature for unnamed and undiscovered elements, oganesson is sometimes known as eka-radon (until the 1960s as eka-emanation, emanation being the old name for radon).

[91] Although widely used in the chemical community on all levels, from chemistry classrooms to advanced textbooks, the recommendations were mostly ignored among scientists in the field, who called it "element 118", with the symbol of E118, (118), or simply 118.

[102][l] In June 2016, IUPAC announced that the discoverers planned to give the element the name oganesson (symbol: Og).

The discovery of element 118 was by scientists at the Joint Institute for Nuclear Research in Russia and at the Lawrence Livermore National Laboratory in the US, and it was my colleagues who proposed the name oganesson.

[103]The naming ceremony for moscovium, tennessine, and oganesson was held on 2 March 2017 at the Russian Academy of Sciences in Moscow.

[104] In a 2019 interview, when asked what it was like to see his name in the periodic table next to Einstein, Mendeleev, the Curies, and Rutherford, Oganessian responded:[102] Not like much!

[106] This is because of the ever-increasing Coulomb repulsion of protons, so that the strong nuclear force cannot hold the nucleus together against spontaneous fission for long.

[107] However, researchers in the 1960s suggested that the closed nuclear shells around 114 protons and 184 neutrons should counteract this instability, creating an island of stability in which nuclides could have half-lives reaching thousands or millions of years.

The members of this group are usually inert to most common chemical reactions (for example, combustion) because the outer valence shell is completely filled with eight electrons.

[3] Consequently, some expect oganesson to have similar physical and chemical properties to other members of its group, most closely resembling the noble gas above it in the periodic table, radon.

[3] The reason for the possible enhancement of the chemical activity of oganesson relative to radon is an energetic destabilization and a radial expansion of the last occupied 7p-subshell.

[3] Because of its tremendous polarizability, oganesson is expected to have an anomalously low first ionization energy of about 860 kJ/mol, similar to that of cadmium and less than those of iridium, platinum, and gold.

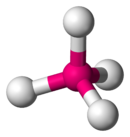

4 has a square planar molecular geometry.

4 is predicted to have a tetrahedral molecular geometry.