Olbers's paradox

[1] The darkness of the night sky is one piece of evidence for a dynamic universe, such as the Big Bang model.

That model explains the observed non-uniformity of brightness by invoking expansion of the universe, which increases the wavelength of visible light originating from the Big Bang to microwave scale via a process known as redshift.

The resulting microwave radiation background has wavelengths much longer (millimeters instead of nanometers), which appear dark to the naked eye and bright for a radio receiver.

Although he was not the first to describe it, the paradox is popularly named after the German astronomer Heinrich Wilhelm Olbers (1758–1840).

The first one to address the problem of an infinite number of stars and the resulting heat in the Cosmos was Cosmas Indicopleustes, a 6th-century Greek monk from Alexandria, who states in his Topographia Christiana: "The crystal-made sky sustains the heat of the Sun, the moon, and the infinite number of stars; otherwise, it would have been full of fire, and it could melt or set on fire.

[3] Kepler also posed the problem in 1610, and the paradox took its mature form in the 18th-century work of Halley and Cheseaux.

Harrison argues that the first to set out a satisfactory resolution of the paradox was Lord Kelvin, in a little known 1901 paper,[5] and that Edgar Allan Poe's essay Eureka (1848) curiously anticipated some qualitative aspects of Kelvin's argument:[1] Were the succession of stars endless, then the background of the sky would present us a uniform luminosity, like that displayed by the Galaxy – since there could be absolutely no point, in all that background, at which would not exist a star.

The only mode, therefore, in which, under such a state of affairs, we could comprehend the voids which our telescopes find in innumerable directions, would be by supposing the distance of the invisible background so immense that no ray from it has yet been able to reach us at all.

The poet Edgar Allan Poe suggested in Eureka: A Prose Poem that the finite age of the observable universe resolves the apparent paradox.

However, the Big Bang theory seems to introduce a new problem: it states that the sky was much brighter in the past, especially at the end of the recombination era, when it first became transparent.

This problem is addressed by the fact that the Big Bang theory also involves the expansion of the universe, which can cause the energy of emitted light to be reduced via redshift.

More specifically, the extremely energetic radiation from the Big Bang has been redshifted to microwave wavelengths (1100 times the length of its original wavelength) as a result of the cosmic expansion, and thus forms the cosmic microwave background radiation.

This explains the relatively low light densities and energy levels present in most of our sky today despite the assumed bright nature of the Big Bang.

The redshift hypothesised in the Big Bang model would by itself explain the darkness of the night sky even if the universe were infinitely old.

Thus the observed radiation density (the sky brightness of extragalactic background light) can be independent of finiteness of the universe.

However, the steady-state model does not predict the angular distribution of the microwave background temperature accurately (as the standard ΛCDM paradigm does).

[4] So the sky is about five hundred billion times darker than it would be if the universe was neither expanding nor too young to have reached equilibrium yet.

However, recent observations increasing the lower bound on the number of galaxies suggest UV absorption by hydrogen and reemission in near-IR (not visible) wavelengths also plays a role.

[14] A different resolution, which does not rely on the Big Bang theory, was first proposed by Carl Charlier in 1908 and later rediscovered by Benoît Mandelbrot in 1974.

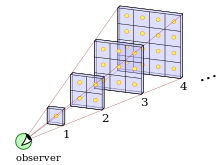

[citation needed] They both postulated that if the stars in the universe were distributed in a hierarchical fractal cosmology (e.g., similar to Cantor dust)—the average density of any region diminishes as the region considered increases—it would not be necessary to rely on the Big Bang theory to explain Olbers's paradox.

[15][16][17] Moreover, the majority of cosmologists accept the cosmological principle,[citation needed] which assumes that matter at the scale of billions of light years is distributed isotropically.

Contrarily, fractal cosmology requires anisotropic matter distribution at the largest scales.