Old Aramaic

Emerging as the language of the city-states of the Arameans in the Fertile Crescent in the Early Iron Age, Old Aramaic was adopted as a lingua franca, and in this role was inherited for official use by the Achaemenid Empire during classical antiquity.

After the fall of the Achaemenid Empire, local vernaculars became increasingly prominent, fanning the divergence of an Aramaic dialect continuum and the development of differing written standards.

The language is considered to have given way to Middle Aramaic by the 3rd century (a conventional date is the rise of the Sasanian Empire in 224 AD).

"Ancient Aramaic" refers to the earliest known period of the language, from its origin until it becomes the lingua franca of the Fertile Crescent and Bahrain.

It seems that in time, a more refined alphabet, suited to the needs of the language, began to develop from this in the eastern regions of Aram.

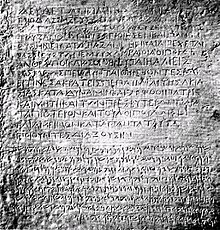

Imperial Aramaic was highly standardised; its orthography was based more on historical roots than any spoken dialect, and the inevitable influence of Old Persian gave the language a new clarity and robust flexibility.

For centuries after the fall of the Achaemenid Empire (in 331 BCE), Imperial Aramaic or a similar dialect would remain an influence on the various native Iranian languages.

[9] One of the largest collections of Imperial Aramaic texts is that of the Persepolis fortification tablets, which number about five hundred.

The texts, which were rendered on leather, reflect the use of Aramaic in the fourth century BCE Achaemenid administration of Bactria and Sogdia.

[12] Old Aramaic and Biblical Hebrew both form part of the group of Northwest Semitic languages, and during antiquity, there may still have been substantial mutual intelligibility.

It is theorized that some Biblical Aramaic material originated in both Babylonia and Judaea before the fall of the Achaemenid dynasty.

In the third century BCE, Koine Greek overtook Aramaic as the common language in Egypt and Syria.

However, a post-Achaemenid Aramaic continued to flourish from Judea, Assyria, Mesopotamia, through the Syrian Desert and into northern Arabia and Parthia.

Under the category of post-Achaemenid is Hasmonaean Aramaic, the official language of the Hasmonean dynasty of Judaea (142–37 BCE).

The Galilean Targum was not considered an authoritative work by other communities, and documentary evidence shows that its text was amended.

The Nabataean language was the Western Aramaic variety used by the Nabateans of the Negev, including the kingdom of Petra.

The kingdom (c. 200 BCE–106 CE) covered the east bank of the Jordan River, the Sinai Peninsula and northern Arabia.

The use of written Aramaic in the Achaemenid bureaucracy also precipitated the adoption of Aramaic-derived scripts to render a number of Middle Iranian languages.

The Sasanian Empire, which succeeded the Parthian Arsacids in the mid-3rd century CE, subsequently inherited/adopted the Parthian-mediated Aramaic-derived writing system for their own Middle Iranian ethnolect as well.

However, the diverse regional dialects of Late Ancient Aramaic continued alongside them, often as simple, spoken languages.

[23] On the upper reaches of the Tigris, East Mesopotamian Aramaic flourished, with evidence from Hatra, Assur and the Tur Abdin.

Tatian, the author of the gospel harmony known as the Diatessaron, came from the Seleucid Empire and perhaps wrote his work (172 CE) in East Mesopotamian rather than Edessan Aramaic or Greek.

Aramaic came to coexist with Canaanite dialects, eventually completely displacing Phoenician and Hebrew around the turn of the 4th century CE.

Old Judaean literature can be found in various inscriptions and personal letters, preserved quotations in the Talmud and receipts from Qumran.

Samaria had its distinctive Samaritan Aramaic, where the consonants he, heth and ayin all became pronounced the same as aleph, presumably a glottal stop.