Proto-Germanic language

[2] A defining feature of Proto-Germanic is the completion of the process described by Grimm's law, a set of sound changes that occurred between its status as a dialect of Proto-Indo-European and its gradual divergence into a separate language.

The alternative term "Germanic parent language" may be used to include a larger scope of linguistic developments, spanning the Nordic Bronze Age and Pre-Roman Iron Age in Northern Europe (second to first millennia BC) to include "Pre-Germanic" (PreGmc), "Early Proto-Germanic" (EPGmc) and "Late Proto-Germanic" (LPGmc).

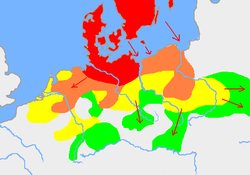

[citation needed] According to Mallory, Germanicists "generally agree" that the Urheimat ('original homeland') of the Proto-Germanic language, the ancestral idiom of all attested Germanic dialects, was primarily situated in an area corresponding to the extent of the Jastorf culture.

[11][12][13][note 3] Early Germanic expansion in the Pre-Roman Iron Age (fifth to first centuries BC) placed Proto-Germanic speakers in contact with the Continental Celtic La Tène horizon.

Winfred P. Lehmann regarded Jacob Grimm's "First Germanic Sound Shift", or Grimm's law, and Verner's law,[note 4] (which pertained mainly to consonants and were considered for many decades to have generated Proto-Germanic) as pre-Proto-Germanic and held that the "upper boundary" (that is, the earlier boundary) was the fixing of the accent, or stress, on the root syllable of a word, typically on the first syllable.

[20] Proto-Indo-European had featured a moveable pitch-accent consisting of "an alternation of high and low tones"[21] as well as stress of position determined by a set of rules based on the lengths of a word's syllables.

For Lehmann, the "lower boundary" was the dropping of final -a or -e in unstressed syllables; for example, post-PIE *wóyd-e > Gothic wait, 'knows'.

Elmer H. Antonsen agreed with Lehmann about the upper boundary[22] but later found runic evidence that the -a was not dropped: ékwakraz … wraita, 'I, Wakraz, … wrote (this)'.

It contained many innovations that were shared with other Indo-European branches to various degrees, probably through areal contacts, and mutual intelligibility with other dialects would have remained for some time.

Other likely Celtic loans include *ambahtaz 'servant', *brunjǭ 'mailshirt', *gīslaz 'hostage', *īsarną 'iron', *lēkijaz 'healer', *laudą 'lead', *Rīnaz 'Rhine', and *tūnaz, tūną 'fortified enclosure'.

[note 5] These loans would likely have been borrowed during the Celtic Hallstatt and early La Tène cultures when the Celts dominated central Europe, although the period spanned several centuries.

[note 6] The words could have been transmitted directly by the Scythians from the Ukraine plain, groups of whom entered Central Europe via the Danube and created the Vekerzug Culture in the Carpathian Basin (sixth to fifth centuries BC), or by later contact with Sarmatians, who followed the same route.

[note 7] Theo Vennemann has hypothesized a Basque substrate and a Semitic superstrate in Germanic; however, his speculations, too, are generally rejected by specialists in the relevant fields.

Diachronically, the rise of consonant gradation in Germanic can be explained by Kluge's law, by which geminates arose from stops followed by a nasal in a stressed syllable.

[52] The idea has been described as "methodically unsound", because it attempts to explain the phonological phenomenon through psycholinguistic factors and other irregular behaviour instead of exploring regular sound laws.

The reconstruction of grading paradigms in Proto-Germanic explains root alternations such as Old English steorra 'star' < *sterran- vs. Old Frisian stera 'id.'

[62] One example, without a laryngeal, includes the class II weak verbs (ō-stems) where a -j- was lost between vowels, so that -ōja → ōa → ô (cf.

However, this view was abandoned since languages in general do not combine distinctive intonations on unstressed syllables with contrastive stress and vowel length.

ē₂ is uncertain as a phoneme and only reconstructed from a small number of words; it is posited by the comparative method because whereas all provable instances of inherited (PIE) *ē (PGmc.

It probably continues PIE ēi, and it may have been in the process of transition from a diphthong to a long simple vowel in the Proto-Germanic period.

The earlier and much more frequent source was word-final -n (from PIE -n or -m) in unstressed syllables, which at first gave rise to short -ą, -į, -ų, long -į̄, -ę̄, -ą̄, and overlong -ę̂, -ą̂.

[69] Another source, developing only in late Proto-Germanic times, was in the sequences -inh-, -anh-, -unh-, in which the nasal consonant lost its occlusion and was converted into lengthening and nasalisation of the preceding vowel, becoming -ą̄h-, -į̄h-, -ų̄h- (still written as -anh-, -inh-, -unh- in this article).

Due to the emergence of a word-initial stress accent, vowels in unstressed syllables were gradually reduced over time, beginning at the very end of the Proto-Germanic period and continuing into the history of the various dialects.

Furthermore, Proto-Romance and Middle Indic of the fourth century AD—contemporaneous with Gothic—were significantly simpler than Latin and Sanskrit, respectively, and overall probably no more archaic than Gothic.

Probably the most far-reaching alternation was between [*f, *þ, *s, *h, *hw] and [*b, *d, *z, *g, *gw], the voiceless and voiced fricatives, known as Grammatischer Wechsel and triggered by the earlier operation of Verner's law.

It was found in various environments: Another form of alternation was triggered by the Germanic spirant law, which continued to operate into the separate history of the individual daughter languages.

I-mutation was the most important source of vowel alternation, and continued well into the history of the individual daughter languages (although it was either absent or not apparent in Gothic).

Similarly, the Latin imperfect and pluperfect stem from Italic innovations and are not cognate with the corresponding Greek or Sanskrit forms; and while the Greek and Sanskrit pluperfect tenses appear cognate, there are no parallels in any other Indo-European languages, leading to the conclusion that this tense is either a shared Greek-Sanskrit innovation or separate, coincidental developments in the two languages.

On the evidence of Gothic—the only Germanic language with a reflex of the Proto-Germanic passive—the passive voice had a significantly reduced inflectional system, with a single form used for all persons of the dual and plural.

Note that although Old Norse (like modern Faroese and Icelandic) has an inflected mediopassive, it is not inherited from Proto-Germanic, but is an innovation formed by attaching the reflexive pronoun to the active voice.