Indo-Aryan languages

As of 2024, there are more than 1.5 billion speakers, primarily concentrated east of the Indus river in Bangladesh, North India, Eastern Pakistan, Sri Lanka, Maldives and Nepal.

[4] Moreover, apart from the Indian subcontinent, large immigrant and expatriate Indo-Aryan–speaking communities live in Northwestern Europe, Western Asia, North America, the Caribbean, Southeast Africa, Polynesia and Australia, along with several million speakers of Romani languages primarily concentrated in Southeastern Europe.

Anton I. Kogan, in 2016, conducted a lexicostatistical study of the New Indo-Aryan languages based on a 100-word Swadesh list, using techniques developed by the glottochronologist and comparative linguist Sergei Starostin.

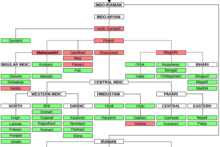

Since its proposal by Rudolf Hoernlé in 1880 and refinement by George Grierson it has undergone numerous revisions and a great deal of debate, with the most recent iteration by Franklin Southworth and Claus Peter Zoller based on robust linguistic evidence (particularly an Outer past tense in -l-).

Dardic was first formulated by George Abraham Grierson in his Linguistic Survey of India but he did not consider it to be a subfamily of Indo-Aryan.

The Western Indo-Aryan languages are thought to have diverged from their northwestern counterparts, although they have a common antecedent in Shauraseni Prakrit.

Some theonyms, proper names, and other terminology of the Late Bronze Age Mitanni civilization of Upper Mesopotamia exhibit an Indo-Aryan superstrate.

The numeral aika "one" is of particular importance because it places the superstrate in the vicinity of Indo-Aryan proper as opposed to Indo-Iranian in general or early Iranian (which has aiva).

The earliest evidence of the group is from Vedic Sanskrit, that is used in the ancient preserved texts of the Indian subcontinent, the foundational canon of the Hindu synthesis known as the Vedas.

The Indo-Aryan superstrate in Mitanni is of similar age to the language of the Rigveda, but the only evidence of it is a few proper names and specialized loanwords.

Some of these dialects showed considerable literary production; the Śravakacāra of Devasena (dated to the 930s) is now considered to be the first Hindi book.

The largest languages that formed from Apabhraṃśa were Bengali, Bhojpuri, Hindustani, Assamese, Sindhi, Gujarati, Odia, Marathi, and Punjabi.

In the Central Zone Hindi-speaking areas, for a long time the prestige dialect was Braj Bhasha, but this was replaced in the 13th century by Dehlavi-based Hindustani.

[42]: 1 Based on the systematicity of sound changes, linguists have concluded that the ethnonyms Domari and Romani derive from the Indo-Aryan word ḍom.

The language retains many features similar to Punjabi and the Western Hindi dialects, while also bearing some influence from Tajik Persian.

[46] Romani varieties, which are mainly spoken throughout Europe, are noted for their relatively conservative nature; maintaining the Middle Indo-Aryan present-tense person concord markers, alongside consonantal endings for nominal case.

Moreover, Romani shares an innovative pattern of past-tense person, which corresponds to Dardic languages, such as Kashmiri and Shina.

Research conducted by nineteenth-century scholars Pott (1845) and Miklosich (1882–1888) demonstrated that the Romani language is most aptly designated as a New Indo-Aryan language (NIA), as opposed to Middle Indo-Aryan (MIA); establishing that proto-Romani speakers could not have left India significantly earlier than AD 1000.

Kholosi, Jadgali, and Luwati represent offshoots of the Sindhic subfamily of Indo-Aryan that have established themselves in the Persian Gulf region, perhaps through sea-based migrations.

The normative system of New Indo-Aryan stops consists of five places of articulation: labial, dental, "retroflex", palatal, and velar, which is the same as that of Sanskrit.

The "retroflex" position may involve retroflexion, or curling the tongue to make the contact with the underside of the tip, or merely retraction.

Moving away from the normative system, some languages and dialects have alveolar affricates [ts] instead of palatal, though some among them retain [tʃ] in certain positions: before front vowels (esp.

The addition of a retroflex affricate to this in some Dardic languages maxes out the number of stop positions at seven (barring borrowed /q/), while a reduction to the inventory involves *ts > /s/, which has happened in Assamese, Chittagonian, Sinhala (though there have been other sources of a secondary /ts/), and Southern Mewari.

Vowel typologies are varied across Indo-Aryan due to diachronic mergers and (in some cases) splits, as well as different accounts by linguists for even the widely-spoken languages.

[w] In many Indo-Aryan languages, the literary register is often more archaic and utilises a different lexicon (Sanskrit or Perso-Arabic) than spoken vernacular.

In the context of South Asia, the choice between the appellations "language" and "dialect" is a difficult one, and any distinction made using these terms is obscured by their ambiguity.

In one general colloquial sense, a language is a "developed" dialect: one that is standardised, has a written tradition and enjoys social prestige.

As there are degrees of development, the boundary between a language and a dialect thus defined is not clear-cut, and there is a large middle ground where assignment is contestable.

Though seemingly a "proper" linguistics sense of the terms, it is still problematic: methods that have been proposed for quantifying difference (for example, based on mutual intelligibility) have not been seriously applied in practice; and any relationship established in this framework is relative.