Old Serbia

[6] Milovan Radovanović claims that although the term was not attested until the 19th century it emerged in the colloquial speech of the Serb population[7] who lived in territories of the Habsburg monarchy after the Great Migrations.

[10] For Karadžić, the Slavic inhabitants of Macedonia were Serbian, detached from its Serb past due to Ottoman rule and propaganda activities undertaken by the Bulgarian Orthodox Church.

[13] The critical treatment of facts was damaged by the invocation of the past for the justification of present and future claims, and by the mixture of history and contemporary issues.

[16] Serbian engagement with the region started in 1868 with the establishment of the Educational Council (Prosvetni odbor) that opened schools and sent Serb instructors and textbooks to Macedonia and Old Serbia.

[23] With the 1878 Treaty of Berlin, Serbia received full sovereignty and made territorial gains around this time, acquiring the districts of Niš, Pirot, Vranje and Toplica [sr].

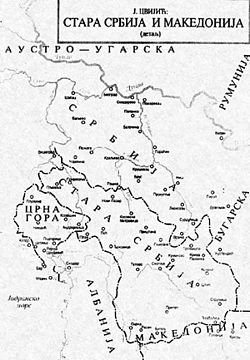

[32] Cvijić continuously changed his maps to include or exclude "Macedonian Slavs", altering the location of the boundary between Bulgarians and Serbs and readjusting the colour scheme to show Macedonia as nearer to Serbia.

[37] Old Serbia as a term evoked strong symbolism and message regarding Serb historical rights to the land whose demographics were seen to have been altered in the Ottoman period to favour Albanians at the conclusion of the seventeenth century.

[29] The more prominent theory stated that Ottoman aims were to split the Serbian principality from Old Serbia that involved installing Muslim Albanians into the area.

[29] The theory concluded that Serbian abilities were diminished for liberation wars of the future as Albanians formed a "living wall" spanning from Kosovo to the Pĉinja area, limiting the spread of Serb influence.

[29] Before the events of the Berlin Congress, only a small number of Serbian accounts existed that described Old Serbia and Macedonia in the early nineteenth century.

[34] Travels through Old Serbia were presented as a movement through time and observations by writers focused on the medieval period and landscape geography, as opposed to the reality of the day.

[42][43] The links travelogues drew to Old Serbia with inhabitants under threat had an important impact through discourse in connecting an emerging Serb national identity with Kosovo.

[42] Serb travelogues defined Old Serbia in its minimum extent as being Kosovo and at its wider range as encompassing north western Macedonia and northern Albania.

[44] Travellers writing about Macedonia used cultural and socio-linguistic depictions to state that local Christian Slavic inhabitants were exposed to Bulgarian propaganda that inhibited their ability to become Serbian.

[46] In areas where the population was mainly Albanian, the appropriation undertaken by travel writers was reinforced through narratives of history, positions based on economic and geographic issues, at times that involved fabricating information and creating the room for discrimination on cultural and racial grounds toward non-Slavs.

[48] The process allowed the lands of Old Serbia to be denoted as Serbian and implied a future removal of political rights and ability for self determination from non-Slavic inhabitants such as Albanians, whom were viewed as the cultural and racial "other", unhygienic, and a danger.

Following the collapse of the Ottoman Empire, Serb publications aiming to counter Albanian interests and to justify Serbian historical claims in Kosovo and Macedonia through the recreation of Old Serbia in those territories appeared.

[54] At the end of the First World War, Serbia became part of the Kingdom of Yugoslavia and the state placed its efforts toward speeding up the incorporation of newly acquired lands such as Kosovo, Macedonia and Sandžak.

[59] The stances and opinions of the early twentieth century Serbian intelligentsia have left a legacy in the political space as those views are used in modern discourses of Serb nationalism to uphold nationalistic claims.