Balkan Wars

The First Balkan War began on 8 October 1912, when the League member states attacked the Ottoman Empire, and ended eight months later with the signing of the Treaty of London on 30 May 1913.

Serbia had gained substantial territory during the Russo-Turkish War (1877–1878), while Greece acquired Thessaly in 1881 (although it lost a small area back to the Ottoman Empire in 1897) and Bulgaria (an autonomous principality since 1878) incorporated the formerly distinct province of Eastern Rumelia (1885).

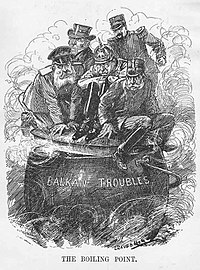

The First Balkan War had some main causes, which included:[14][8][15] Throughout the 19th century, the Great Powers shared different aims over the "Eastern Question" and the integrity of the Ottoman Empire.

Russia wanted access to the "warm waters" of the Mediterranean from the Black Sea; so, it pursued a pan-Slavic foreign policy and therefore supported Bulgaria and Serbia.

The Habsburgs also saw a strong Ottoman presence in the area as a counterweight to the Serbian nationalistic call to their own Serb subjects in Bosnia, Vojvodina and other parts of the empire.

The Greeks of the autonomous Cretan State proclaimed unification with Greece, though the opposition of the Great Powers prevented the latter action from taking practical effect.

Instead, the Serbian government (PM: Nikola Pašić) looked to formerly Serb territories in the south, notably "Old Serbia" (the Sanjak of Novi Pazar and the province of Kosovo).

The Christian Balkan countries were forced to take action and saw this as an opportunity to promote their national agenda by expanding in the territories of the falling empire and liberating their enslaved co-patriots.

The then Bulgarian Minister of Foreign Affairs General Stefan Paprikov stated in 1909 that, "It will be clear that if not today then tomorrow, the most important issue will again be the Macedonian Question.

At that time, the Balkan states had been able to maintain armies that were both numerous, in relation to each country's population, and eager to act, being inspired by the idea that they would free enslaved parts of their homeland.

The Empire withdrew its ambassadors from Sofia, Belgrade, and Athens, while the Bulgarian, Serbian and Greek diplomats left the Ottoman capital delivering the war declaration on 4/17 of October 1912.

[15] The three Slavic allies (Bulgaria, Serbia, and Montenegro) had laid out extensive plans to coordinate their war efforts, in continuation of their secret prewar settlements and under close Russian supervision (Greece was not included).

Serbia attacked south towards Skopje and Monastir and then turned west to present-day Albania, reaching the Adriatic, while a second Army captured Kosovo and linked with the Montenegrin forces.

Before the Greeks entered the city, a German warship whisked the former sultan Abdul Hamid II out of Thessaloniki to continue his exile, across the Bosporus from Constantinople.

Greece expanded its occupied area and teamed up with the Serbian army to the northwest, while its main forces turned east towards Kavala, reaching the Bulgarians.

In the joint Serbian-Montenegrin theater of operation, the Montenegrin army besieged and captured the Shkodra, ending the Ottoman presence in Europe west of the Çatalca line after nearly 500 years.

[29] This event led to the formation of two ‘de facto’ military occupation zones on Macedonian territory, as Greece and Serbia tried to create a common border.

[30] Assured by the clauses of the Treaty that it would receive what it considered its fair share of Macedonia, Bulgaria sent almost all of its troops to the Thracian front, which was expected to, and eventually did indeed, decide the outcome of the war.

As the establishment of an independent Albanian state, brokered by Italy and Austria-Hungary, deprived the Serbs of their much-coveted Adriatic port, they demanded not only the entire Contested Zone, but also all of the Uncontested one they had occupied.

On the night of 29 June 1913, the Bulgarian army made an ill-advised attempt to gain an advantage in the negotiations by pushing out Serbian and Greek forces out of several disputed territories without a battle plan or declaration of war, naively thinking that this would be regarded as a mere altercation.

Tsar Nicholas II of Russia, being well informed, tried to stop the upcoming conflict on 8 June, by sending an identical personal message to the Kings of Bulgaria and Serbia, offering to act as arbitrator according to the provisions of the 1912 Serbo-Bulgarian treaty.

Its forces encountered little resistance and, by the time the Greeks accepted the Bulgarian request for an armistice, they had reached Vrazhdebna, 11 km (7 mi) from the center of Sofia.

They attacked, and, finding no opposition, managed to win back all of their lands which had been officially ceded to Bulgaria as a part of the Sofia Conference in 1914, i.e. Thrace with its fortified city of Adrianople, regaining an area in Europe which was only slightly larger than the present-day European territory of the Republic of Turkey.

Although there was an official consensus between the European Powers over the territorial integrity of the Ottoman Empire, which led to a stern warning to the Balkan states, unofficially each of them took a different diplomatic approach due to their conflicting interests in the area.

Second, the clearly pro-Serbian position Russia had been forced to take in the conflict, mainly due to the disagreements over land partitioning between Serbia and Bulgaria, caused a permanent break-up between the two countries.

Accordingly, Bulgaria reverted its policy to one closer to the Central Powers' understanding over an anti-Serbian front, due to its new national aspirations, now expressed mainly against Serbia.

This was a position that inevitably drew Russia into an unwelcome World War with devastating results since it was less prepared (both militarily and socially) for that event than any other Great Power.

This meant that when a Serbian backed organization assassinated Archduke Franz Ferdinand of Austria, the reform-minded heir to the Austro-Hungarian throne, causing the 1914 July Crisis, the conflict quickly escalated and resulted in the First World War.

The Ottoman Empire lost all its European territories west of the River Maritsa as a result of the two Balkan Wars, which thus delineated present-day Turkey's western border.

[55] The unexpected fall and sudden relinquishing of Turkish-dominated European territories created a traumatic event amongst many Turks that triggered the ultimate collapse of the empire itself within five years.