Old soldiers' home

It is an independent charity and relies partly upon donations to cover day-to-day running costs to provide care and accommodation for veterans.

Any man or woman who is over the age of 65 and served as a regular soldier may apply to become a Chelsea Pensioner (i.e. a resident), on the basis they have found themselves in a time of need and are "of good character".

The in-pensioners are formed into three companies, each headed by a Captain of Invalids (an ex-Army officer responsible for the 'day to day welfare, management and administration' of the pensioners under his charge).

The ex-officio chairman of the board is HM Paymaster General (whose predecessor Sir Stephen Fox was instrumental in founding the Hospital in the seventeenth century).

The purpose of the Board is 'to guide the development of The Royal Hospital, ensuring the care and well-being of the Chelsea Pensioners who live there and safeguarding the historic buildings and grounds, which it owns in trust'.

Sir Christopher Wren and his assistant Nicholas Hawksmoor gave their services free of charge as architects of the new Royal Hospital.

In 1705 an additional £6,472 was paid into the fund, comprising the liquidated value of estates belonging to the recently hanged pirate Captain William Kidd.

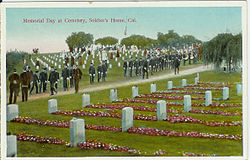

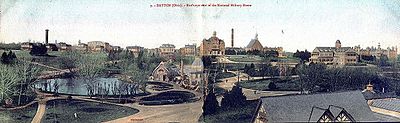

[13] General Winfield Scott founded the Soldier's Home in Washington, D.C., and another (since fallen into disuse) in Harrodsburg, Kentucky with about $118,000 in leftover proceeds of assessments on occupied Mexican towns and the sale of captured tobacco in the Mexican–American War.

It is located on a 250-acre (1.0 km2) wooded campus overlooking the U.S. Capitol in the heart of Washington, D.C., three miles from the White House,[15] and continues to serve as a retirement home for U.S. enlisted men and women.

Both the Washington, D.C., and Gulfport soldiers' and sailors' homes are funded through a small monthly contribution from the pay of members of the U.S. Armed Services.

Various female benevolent societies pushed for the creation of a long-term care federal or state soldier home system at the end of the war.

Soldier homes in major cities were among the earliest, usually starting more as hotels for men passing through town, but increasingly taking on disabled servicemen.

[20] Women activists also helped establish disabled soldiers' homes in Boston, Chicago, and Milwaukee, or in conjunction with the U.S. Sanitary Commission in 25 other cities.

[21] During the Civil War, the US Sanitary Commission provided Union servicemen "[t]emporary aid and protection,—food, lodging, care, etc.,—for soldiers in transitn[sic], chiefly the discharged, disabled, and furloughed."