António de Oliveira Salazar

The conditions he proposed to control spending were refused, he quickly resigned, and in two hours he was on a train back to Coimbra University, explaining that because of the frequent disputes and general disorder in the government, he could not do his work properly.

At no stage did it appear that Salazar wished it to fulfill the central role the Fascist Party had acquired in Mussolini's Italy, in fact it was meant to be a platform of conservatism, not a revolutionary vanguard.

Salazar denounced the National Syndicalists as "inspired by certain foreign models" (meaning German Nazism) and condemned their "exaltation of youth, the cult of force through direct action, the principle of the superiority of state political power in social life, [and] the propensity for organising masses behind a single leader" as fundamental differences between fascism and the Catholic corporatism of the Estado Novo.

[61] Although Salazar admired Mussolini and was influenced by his Labour Charter of 1927,[46] he distanced himself from fascist dictatorship, which he considered a pagan Caesarist political system that recognised neither legal nor moral limits.

[62] Scholars such as Stanley G. Payne, Thomas Gerard Gallagher, Juan José Linz, António Costa Pinto, Roger Griffin, Robert Paxton and Howard J. Wiarda, prefer to consider the Portuguese Estado Novo as conservative authoritarian rather than fascist.

The secret police existed not only to protect national security in a modern sense, but also to monitor the population, apply censorship, and suppress the regime's political opponents, especially those associated with the international communist movement or the Soviet Union.

Emídio Santana [pt], founder of the Sindicato Nacional dos Metalúrgicos ("National Syndicate of Metallurgists") and an anarcho-syndicalist who was involved in clandestine activities against the dictatorship, attempted to assassinate Salazar on 4 July 1937.

[100][101] In September 1940, Winston Churchill wrote to Salazar to congratulate him for his policy of keeping Portugal out of the war, avowing that "as so often before during the many centuries of the Anglo-Portuguese alliance, British and Portuguese interests are identical on this vital question.

When in May 1943, in the Third Washington Conference, codenamed Trident, the conferees agreed on the occupation of the Azores (Operation Alacrity)[105][106] the British Ambassador reacted to the US State Department's suggestion as "particularly ill-timed and incomprehensible at the present juncture".

Use of Lajes Field reduced flying time between Brazil and West Africa from 70 hours to 40, a considerable reduction that enabled aircraft to make almost twice as many crossings, clearly demonstrating the geographic value of the Azores during the war.

[122] Tom Gallagher argues that Branquinho's case has been largely overlooked, probably because he was coordinating his actions with Salazar, which weakens the core argument in the Sousa Mendes' legend that he was defying a tyrannical superior.

[121] Tom Gallagher is not alone in classifying as disproportionate the attention given to Sousa Mendes' episode; the Portuguese historian Diogo Ramada Curto also thinks that "the myth of an Aristides who opposed Salazar and capable of acting individually, in isolation, is a late invention that rigorous historical analysis does not confirm.

Francisco de Paula Leite Pinto, at that time the General Manager of the Beira Alta Railway, which operated the line from Figueira da Foz to the Spanish frontier, organized several trains that brought refugees from Berlin and other European cities to Portugal.

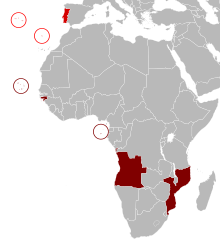

[135] Although the Estatuto do Indigenato ('Indigenous Statute') set standards for indigenes to obtain Portuguese citizenship until it was abolished in 1961, the conditions of the native populations of the colonies were still harsh, and they suffered inferior legal status under its policies.

Salazar's reluctance to travel abroad, his increasing determination not to grant independence to the colonies, and his refusal to grasp the impossibility of his regime outliving him marked the final years of his tenure.

In 1961, General Júlio Botelho Moniz, after being nominated Minister of Defense, tried to convince President Américo Tomás in a constitutional "coup d'état" to remove an aged Salazar from the premiership.

His political ally Francisco da Costa Gomes was nonetheless allowed to publish a letter in the newspaper Diário Popular reiterating his view that a military solution in Africa was unlikely.

After Rhodesia proclaimed its Unilateral Declaration of Independence from Britain in 1965, Portugal supported it economically and militarily through neighbouring Portuguese Mozambique until 1975, even though it never officially recognised the new Rhodesian state, which was governed by a white minority elite.

Furthermore, also unlike Spain, it was one of the 12 founding members of the North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO) in 1949, a reflection of Portugal's role as an ally against communism during the Cold War in spite of its status as the only non-democratic founder.

[154] Conservative Portuguese scholars such as Jaime Nogueira Pinto[155] and Rui Ramos[156] claim that Salazar's early reforms and policies allowed political and financial stability, therefore social order and economic growth.

On the other hand, historians such as the leftist politician Fernando Rosas claim that Salazar's policies from the 1930s to the 1950s led to economic and social stagnation and rampant emigration that turned Portugal into one of the poorest countries in Europe.

[157] Despite the effects of an expensive war effort in African territories against guerrilla groups, Portuguese economic growth from 1960 to 1973 under the Estado Novo created an opportunity for real integration with the developed economies of Western Europe.

[164] There were difficulties in the negotiations that preceded its signing; the Church remained eager to re-establish its influence, whereas Salazar was equally determined to prevent any religious intervention within the political sphere, which he saw as the exclusive preserve of the State.

Paul VI officially announced his intention to take part in the Fiftieth Anniversary celebrations of the first reported Fátima apparition – also the twenty-fifth of the consecration of the world to the Immaculate Heart of Mary by Pius XII – during his General Audience of 3 May 1967.

[16] Tens of thousands paid their last respects at the funeral, at the Requiem that took place at the Jerónimos Monastery, and at the passage of the special train that carried the coffin to his hometown of Vimieiro near Santa Comba Dão, where he was buried according to his wishes in his native soil, in a plain ordinary grave next to his parents.

[183] According to American scholar J. Wiarda, despite certain problems and continued poverty in many sectors, the consensus among historians and economists is that Salazar in the 1930s brought remarkable improvements in the economic sphere, public works, social services and governmental honesty, efficiency and stability.

[184][185] Sir Samuel Hoare, the British Ambassador in Spain, recognised Salazar's crucial role in keeping the Iberian peninsula neutral during World War II, and lauded him.

Rather, he appeared a modest, quiet, and highly intelligent gentleman and scholar ... literally dragged from a professorial chair of political economy in the venerable University of Coimbra a dozen years previously in order to straighten out Portugal's finances, and that his almost miraculous success in this respect had led to the thrusting upon him of other major functions, including those of Foreign Minister and constitution-maker.

"[102] Hayes appreciated Portugal's endeavours to form a truly neutral peninsular bloc with Spain, an immeasurable contribution – at a time when the British and the United States had much less influence – towards counteracting the propaganda and appeals of the Axis.

[155] Nonetheless, the Estado Novo persisted under the direction of Marcelo Caetano, Salazar's longtime aide as well as a well-reputed scholar of the University of Lisbon Law School, statesman and distinguished member of the regime who co-wrote the Constitution of 1933.