Oliver Farm Equipment Company

On November 1, 1960, the White Motor Corporation of Cleveland, Ohio, purchased the Oliver Farm Equipment Company.

For most of them, the market had some time earlier reached a saturation point, and in some instances, their machines were dated and rapidly approaching obsolescence.

By uniting their various and somewhat diverse product lines into a single company, Oliver Farm Equipment immediately became a full-line manufacturer.

James Oliver developed his sand casting process to include rapid chilling of the molten iron near the outside surface of the casting, which resulted in a bottom that had a thick hardened surface with far greater wearability than competing plow bottoms.

Had these vapors been trapped in the mould, they would have caused impurities and would have weakened the plowpoint at the place where it should have been the hardest.

[1]: 107 In January 1885, the plant's mostly Polish workers went on strike in protest of cuts to wages and hours in response to a glut of stock.

[6] Veterans of the Civil War with fixed bayonets finally ejected the strikers from the premises.

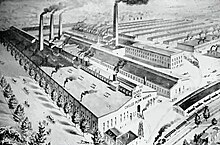

By 1910, the company was manufacturing a wide variety of farm tillage implements in addition to the chilled plow.

At the age of twenty, he transferred from Iowa State College of Agriculture and Mechanical Arts, to the University of Wisconsin–Madison.

[10]: 24 Following their graduation from the University of Wisconsin in 1897, Hart and Parr gathered $3000 in capital and formed the Hart-Parr Gasoline Engine Company.

"There's money around here that might be interested," replied the elder Hart, admitting for the first time that his son's ambition was not folly.

[10]: 24–25 In 1900, as the engine business expanded, Hart and Parr decided to move their company from Madison to Charles City.

1 featured a unique oli-cooled system that used expansion bulbs on oil-cooling radiators.

The tractor at the Smithsonian was used at the George Mitchell farm near Charles City Iowa for twenty-three years.

Later Hart-Parrs were denoted with a two-number name, where the first number stood for horsepower at the draw bar and the pully, respectively.

To help reduce shock, the front and rear axles were spring mounted, a rarity for the time.

Ignition impulse is provided by a battery during start-up and a dynomo once the flywheel gains speed.

The 12-25 model formed the basis for all subsequent Hart-Parr tractors and was equipped with a two-cylinder, slow-speed, un-pressurized water-cooled engine.

[10]: 34 In the blacksmith shop, John Nichols began making various farm tools for local farmers.

For instance, the ground hog's separating unit was largely a slatted apron which pulled the grain across a screen.

[1]: 92 John Nichols and David Shepard realized that the apron style separator was not a technology that was going to work.

Consequently, in 1857, the Nichols and Shepard Company developed the first "vibrator" separating unit for the small grain thresher.

The Nichols and Shepard Company received a patent from the United States government for their "Vibrator" grain separator on January 7, 1862.

However, following the 1930 merger production of the "Oliver" potato diggers moved out of La Crosse, Wisconsin to Chicago, Illinois.

Founded in 1885, the Ann Arbor Agricultural Machine Company became the leading manufacturer of "hay presses" or stationary balers.

[16] Unfortunately, they didn't seem to miss Cletrac at all, and only three years later, crawler tractor production ended at Charles City in 1965.

During the war years of the 1940s Oliver Corporation expanded rapidly into non-agricultural production, most notably in the defense sector.

Oliver also built airplane fuselages for Boeing RB-47E Reconnaissance planes at a Battle Creek, Michigan aviation division set up exclusively for defense contracts.

White Motor Corporation of Cleveland, Ohio had a long history of truck manufacturing.

[17]: 154 White also acquired Cockshutt Farm Equipment of Canada in February 1962, and it was made a subsidiary of Oliver Corporation.