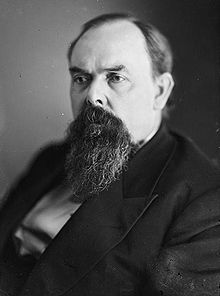

Oliver P. Morton

Leaving school at the age of fifteen, Morton briefly worked as an apothecary's clerk, but left after a dispute with the proprietor and apprenticed as a hat maker.

[1][3][4] In 1852 Morton campaigned and was elected to serve as a circuit court judge, but resigned after only a year; he found that he preferred to practice law.

[5][9] Savvy Republican politicians thought that Morton would be seen as too radical and could not carry the former Know-Nothing vote in the southern half of the state, while a man of Whig antecedents like Lane would.

[10] The campaign focused primarily on the prevailing issues of the nation, including homesteading legislation, tariffs, and the looming possibility of civil war.

[17][18] Three days after the war began on April 12, 1861, at the Battle of Fort Sumter in South Carolina, Governor Morton telegraphed President Lincoln offering 10,000 volunteers from Indiana under arms to help suppress the rebellion.

"[18] Although Morton's efforts were not without controversy and garnered significant opposition from his political adversaries, his greatest strength during the war was his ability to raise volunteers and money for the Union army and to equip them for battle.

[28] Emancipation and the conscription of men to fight a protracted war became major issues that divided Republicans and Democrats during Morton's tenure as governor.

Before the new legislature convened in 1863, Morton began circulating reports that the Democrats intended to seize control of the state government, secede from the Union, and instigate riots.

[32][33][34][35] Without the enactment of an appropriations bill, the state government would not have funds to operate, and the Democrats assumed that Morton would be forced to call a special session and recall the Republicans.

[48] Morton's close observers saw a man of untiring activity, "of unfaltering determination, quick as well as far-seeing..." Restless and full of energy, one newspaper commentated, "He accommodated himself with a kind of cynical indifference to his crippled body, as to a house badly out of repair, and dragged it about with him as a snail does a shell."

"With a superabundance of the quality called 'force,' Senator Morton possesses one of the most terrible natures in public life," and as news correspondent George Alfred Townsend described him: "A dark, determined, brooding and desperate mind is reflected in his warthy complexion and introspective eyes.

By 1866 Morton had come to share the general Republican belief that the only means of guaranteeing loyalty to governments protective of black civil rights must be through giving adult males of every race the franchise.

He championed the passage of the Fifteenth Amendment, and when the Democrats began to resign en masse from the Senate during its debate to prevent a quorum, Morton engineered a maneuver that kept the bill in the docket and allowed it to be passed.

Morton helped shepherd through the bill readmitting Virginia to representation in Congress and voted in favor of the treaty annexing Santo Domingo to the United States.

Later, he countered Senate Foreign Relations Committee chairman Charles Sumner of Massachusetts in a bitter debate over the president's motives and intentions towards the Caribbean nation and its people.

Well-advised sources at the time heard that the Senator from Indiana had been offered a place on the Supreme Court, unofficially, and Justice David Davis took the credit for convincing Grant that the rigor of the job would cause Morton a physical breakdown).

In Indiana the demands for easy money topped the Democrats' list of priority issues, and in the fall of 1874, they carried the state's elections largely on that basis.

After Hayes's supporters made overtures to southern Democrats, offering assurances that the president-elect would take no active role in propping up Republican governors in Louisiana and South Carolina, there were fears that Morton might cause difficulties.

In one speech Morton made it clear that the Democrats must make guarantees of fair play and equal rights for southern blacks, before he would support Hayes's program.

[citation needed] In 1877 Morton was named to lead a committee to investigate charges of bribery made against La Fayette Grover, a newly elected U.S.

[48] Morton's remains were laid in state at the Indiana Statehouse, before their removal to Indianapolis's Roberts Park Methodist Church, where his funeral service was held.

Because the church could not hold the large crowd, thousands of mourners waited outside and followed in a long procession to witness the burial at Indianapolis's Crown Hill Cemetery.

"[62] To his admirers and supporters, Morton was a decisive, effective, ambitious, and energetic leader as governor of Indiana during the Civil War; his detractors would describe him as a wily and power-hungry politician, who shifted his stance on issues to suit prevailing views for his own political gain.

"[67] According to a southern newspaper that opposed his actions, Morton was "a vice-reeking Hoosier bundle of moral and physical rottenness, leprous ulcers and caustic bandages, who loads down with plagues and pollutions the wings of every breeze that sweeps across his loathsome putrefying carcass.

"[68] Other critics and political opponents called him a tyrant and a bully, highlighting his ruthlessness in denouncing, even defaming his enemies, and spreading rumors that he had been a shameless womanizer, forcing himself on every female applicant for favor at the governor's mansion.

One Democratic journalist wrote, "There is not, probably, in this country, a more conscienceless, corrupt, and utterly profligate man in public life than Morton" and "He is rotten physically, morally and politically.

Senator Morton was among the earliest to refuse any share in the so-called "back pay" that Congress awarded its members in 1873, and returned his money to the U.S. Treasury as soon as it was given to him.

A hostile Democratic House scoured the official files for some evidence of bribe-taking or shakedowns in awarding Civil War contracts, and came up empty-handed.

For others, despite holding many positions that angered his opponents, Morton was highly regarded for remaining clean of graft during the war period when corruption was commonplace.

[71] After the poor decision-making of Senators Jesse D. Bright and Graham N. Fitch, Morton succeeded in raising Indiana to national prominence during his lifetime.