James G. Blaine

As Secretary of State, Blaine was a transitional figure, marking the end of an isolationist era in foreign policy and foreshadowing the rise of the American Century that would begin with the Spanish–American War.

[28] Blaine had considered running for the United States House of Representatives from Maine's 4th district in 1860, but agreed to step aside when Anson P. Morrill, a former governor, announced his interest in the seat.

[31] He did clash several times with the leader of the Republicans' radical faction, Thaddeus Stevens of Pennsylvania, firstly over payment of states' debts incurred in supporting the war, and again over monetary policy concerning the new greenback currency.

[35] Blaine voted in favor of these new, harsher measures, but also supported some leniency toward the former rebels when he opposed a bill that would have barred Southerners from attending the United States Military Academy.

[39] A bipartisan group of inflationists, led by Republican Benjamin F. Butler and Democrat George H. Pendleton, wished to preserve the status quo and allow the Treasury to continue to issue greenbacks and even to use them to pay the interest due on pre-war bonds.

[40] During his first three terms in Congress, Blaine had earned for himself a reputation as an expert of parliamentary procedure, and, aside from a growing feud with Roscoe Conkling of New York, had become popular among his fellow Republicans.

In the words of Washington journalist Benjamin Perley Poore, Blaine's "graceful as well as powerful figure, his strong features, glowing with health, and his hearty, honest manner, made him an attractive speaker and an esteemed friend.

[50] Although he supported a general amnesty for former Confederates, Blaine opposed extending it to include Jefferson Davis, and he cooperated with Grant in helping to pass the Civil Rights Act of 1875 in response to increased violence and disenfranchisement of blacks in the South.

Blaine took his case to the House floor on June 5, theatrically proclaiming his innocence and calling the investigation a partisan attack by Southern Democrats in revenge for his exclusion of Jefferson Davis from the amnesty bill of the previous year.

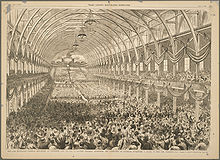

[68] Blaine was nominated by Illinois orator Robert G. Ingersoll in what became a famous speech: This is a grand year—a year filled with recollections of the Revolution ... a year in which the people call for the man who has torn from the throat of treason the tongue of slander, the man who has snatched the mask of Democracy from the hideous face of rebellion ... Like an armed warrior, like a plumed knight, James G. Blaine from the state of Maine marched down the halls of the American Congress and threw his shining lance full and fair against the brazen foreheads of every traitor to his country and every maligner of his fair reputation.

[77] By 1879, there were only 1,155 soldiers stationed in the former Confederacy, and Blaine believed that this small force could never guarantee the civil and political rights of black Southerners—which would mean an end to the Republican party in the South.

As a result, the money supply contracted and the effects of the Panic of 1873 grew worse, making it more expensive for debtors to pay debts they had entered into when currency was less valuable.

[81] Democratic Representative Richard P. Bland of Missouri proposed a bill, which passed the House, that required the United States to coin as much silver as miners could sell the government, thus increasing the money supply and aiding debtors.

He had initially opposed a reciprocity treaty with Canada that would have reduced tariffs between the two nations, but by the end of his time in the Senate, he had changed his mind, believing that Americans had more to gain by increasing exports than they would lose by the risk of cheap imports.

[96] Garfield agreed with his Secretary of State's vision and Blaine called for a Pan-American conference in 1882 to mediate disputes among the Latin American nations and to serve as a forum for talks on increasing trade.

[25] His income from mining and railroad investments was sufficient to sustain the family's lifestyle and to allow for the construction of a vacation cottage, "Stanwood" on Mount Desert Island, Maine, designed by Frank Furness.

[110] Blaine appeared before Congress in 1882 during an investigation into his War of the Pacific diplomacy, defending himself against allegations that he owned an interest in the Peruvian guano deposits being occupied by Chile, but otherwise stayed away from the Capitol.

[120] The Mugwumps, including such men as Carl Schurz and Henry Ward Beecher, were more concerned with morality than with party, and felt Cleveland was a kindred soul who would promote civil service reform and fight for efficiency in government.

[120] However, even as the Democrats gained support from the Mugwumps, they lost some blue-collar workers to the Greenback Party, led by Benjamin F. Butler, Blaine's antagonist from their early days in the House.

Cleveland's supporters rehashed the old allegations from the Mulligan letters that Blaine had corruptly influenced legislation in favor of railroads, later profiting on the sale of bonds he owned in both companies.

[124] At the same time, Democratic operatives accused Blaine and his wife of not having been married when their eldest son, Stanwood, was born in 1851; this rumor was false, however, and caused little excitement in the campaign.

[130] Blaine's hope for Irish defections to the Republican standard were dashed late in the campaign when one of his supporters, Samuel D. Burchard, gave a speech denouncing the Democrats as the party of "Rum, Romanism, and Rebellion.

[136] Blaine and his wife and daughters sailed for Europe in June 1887, visiting England, Ireland, Germany, France, Austria-Hungary, and finally Scotland, where they stayed at the summer home of Andrew Carnegie.

[137] While in France, Blaine wrote a letter to the New-York Tribune criticizing Cleveland's plans to reduce the tariff, saying that free trade with Europe would impoverish American workers and farmers.

[150] Blaine and Harrison had high hopes for the conference, including proposals for a customs union, a pan-American railroad line, and an arbitration process to settle disputes among member nations.

[150] Their overall goal was to extend trade and political influence over the entire hemisphere; some of the other nations understood this and were wary of deepening ties with the United States to the exclusion of European powers.

[161] Blaine was no longer in office when the tribunal began its work, but the result was to allow the hunting once more, albeit with some regulation, and to require the United States to pay damages of $473,151.

[163] After some internal dispute—Blaine wanted conciliation with Italy, Harrison was reluctant to admit fault—the United States agreed to pay an indemnity of $25,000,[k] and normal diplomatic relations resumed.

Although several authors studied Blaine's foreign policy career, including Edward P. Crapol's 2000 work, Muzzey's was the last full-scale biography of the man until Neil Rolde's 2006 book.

Blaine's status as a former Secretary of State who sought to erase evidence of his personal corruption drew parallels to Clinton,[174] while his appeals to anti-Chinese sentiment were compared to Trump's anti-Muslim rhetoric.