Omar Khayyam

This poetry became widely known to the English-reading world in a translation by Edward FitzGerald (Rubaiyat of Omar Khayyam, 1859), which enjoyed great success in the Orientalism of the fin de siècle.

In about 1070 he moved to Samarkand, where he started to compose his famous Treatise on Algebra under the patronage of Abu Tahir Abd al-Rahman ibn ʿAlaq, the governor and chief judge of the city.

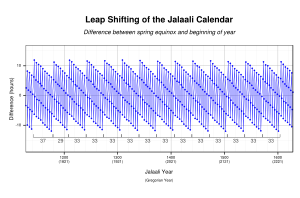

Khayyam was subsequently commissioned to set up an observatory in Isfahan and lead a group of scientists in carrying out precise astronomical observations aimed at the revision of the Persian calendar.

After the death of Malik-Shah and his vizier (murdered, it is thought, by the Ismaili order of Assassins), Khayyam fell from favor at court, and as a result, he soon set out on his pilgrimage to Mecca.

One of his disciples Nizami Aruzi relates the story that sometime during 1112–3 Khayyam was in Balkh in the company of Isfizari (one of the scientists who had collaborated with him on the Jalali calendar) when he made a prophecy that "my tomb shall be in a spot where the north wind may scatter roses over it".

"[6]: 284 Rashed and Vahabzadeh (2000) have argued that because of his thoroughgoing geometrical approach to algebraic equations, Khayyam can be considered the precursor of Descartes in the invention of analytic geometry.

[38]: 158 This task remained open until the sixteenth century, where an algebraic solution of the cubic equation was found in its generality by Cardano, Del Ferro, and Tartaglia in Renaissance Italy.

[8]: 30 George Saliba explains that the term ‘ilm al-nujūm, used in various sources in which references to Khayyam's life and work could be found, has sometimes been incorrectly translated to mean astrology.

"[54]: 224 Khayyam has a short treatise devoted to Archimedes' principle (in full title, On the Deception of Knowing the Two Quantities of Gold and Silver in a Compound Made of the Two).

In his work al-Tanbih ‘ala ba‘d asrar al-maw‘dat fi’l-Qur’an (c. 1160), he quotes one of his poems (corresponding to quatrain LXII of FitzGerald's first edition).

[55]: 11 Hans Heinrich Schaeder in 1934 commented that the name of Omar Khayyam "is to be struck out from the history of Persian literature" due to the lack of any material that could confidently be attributed to him.

[7]: 663 In addition to the Persian quatrains, there are twenty-five Arabic poems attributed to Khayyam which are attested by historians such as al-Isfahani, Shahrazuri (Nuzhat al-Arwah, c. 1201–1211), Qifti (Tārikh al-hukamā, 1255), and Hamdallah Mustawfi (Tarikh-i guzida, 1339).

When they see a man sincere and unremitting in his search for the truth, one who will have nothing to do with falsehood and pretence, they mock and despise him.A literal reading of Khayyam's quatrains leads to the interpretation of his philosophic attitude toward life as a combination of pessimism, nihilism, Epicureanism, fatalism, and agnosticism.

[64] In his preface to the Rubáiyát he claimed that he "was hated and dreaded by the Sufis",[65] and denied any pretense at divine allegory: "his Wine is the veritable Juice of the Grape: his Tavern, where it was to be had: his Saki, the Flesh and Blood that poured it out for him.

[8]: 29 The report has it that upon returning to his native city he concealed his deepest convictions and practised a strictly religious life, going morning and evening to the place of worship.

Khayyam looked at all religions questions with a skeptical eye", continues Hedayat, "and hated the fanaticism, narrow-mindedness, and the spirit of vengeance of the mullas, the so-called religious scholars.

[73]: 75 Other commentators do not accept that Khayyam's poetry has an anti-religious agenda and interpret his references to wine and drunkenness in the conventional metaphorical sense common in Sufism.

This includes Shams Tabrizi (spiritual guide of Rumi),[8]: 58 Najm al-Din Daya who described Omar Khayyam as "an unhappy philosopher, atheist, and materialist",[63]: 71 and Attar who regarded him not as a fellow-mystic but a free-thinking scientist who awaited punishments hereafter.

[7]: 663–664 Seyyed Hossein Nasr argues that it is "reductive" to use a literal interpretation of his verses (many of which are of uncertain authenticity to begin with) to establish Omar Khayyam's philosophy.

[63]: 71 As evidence of Khayyam's faith and/or conformity to Islamic customs, Aminrazavi mentions that in his treatises he offers salutations and prayers, praising God and Muhammad.

[8]: 48 For instance, Al-Bayhaqi's account, which antedates by some years other biographical notices, speaks of Omar as a very pious man who professed orthodox views down to his last hour.

[17]: 174 On the basis of all the existing textual and biographical evidence, the question remains somewhat open,[8]: 11 and as a result Khayyam has received sharply conflicting appreciations and criticisms.

"[7]: 663 Thomas Hyde was the first European to call attention to Khayyam and to translate one of his quatrains into Latin (Historia religionis veterum Persarum eorumque magorum, 1700).

By the 1880s, the book was extremely well known throughout the English-speaking world, to the extent of the formation of numerous "Omar Khayyam Clubs" and a "fin de siècle cult of the Rubaiyat".

[88] For many Muslim reformers, Khayam's verses provided a counterpoint to the conservative norms prevalent in Islamic societies, allowing room for independent thought and a libertine lifestyle.

[88] Figures like Abdullah Cevdet, Rıza Tevfik, and Yahya Kemal utilized Khayyam's themes to justify their progressive ideologies or to celebrate liberal aspects of their lives, portraying him as a cultural, political, and intellectual role model who demonstrated Islam's compatibility with modern conventions.

[88] Similarly, Turkish leftist poets and intellectuals, including Nâzım Hikmet, Sabahattin Eyüboğlu, A. Kadir, and Gökçe, appropriated Khayyam to champion their socialist worldview, imbuing his voice with a humanistic tone in the vernacular.

[88] Conversely, scholars like Dāniş, Tevfik, and Gölpınarlı advocated for source criticism and the identification of authentic quatrains to discern the genuine Khayyam amidst historical perceptions of his sociocultural image.

[90][h]The title of the novel The Moving Finger written by Agatha Christie and published in 1942 was inspired by this quatrain of the translation of Rubaiyat of Omar Khayyam by Edward Fitzgerald.

Over the bleached bones and jumbled residues of numerous civilizations are written the pathetic words, ‘Too late.’ There is an invisible book of life that faithfully records our vigilance or our neglect.