Nastaliq

"[6] Virtually all Safavid authors (like Dust Muhammad or Qadi Ahmad) attributed the invention of nastaliq to Mir Ali Tabrizi, who lived at the end of the 14th and the beginning of the 15th century.

In addition to study of the practice of calligraphy, Elaine Wright also found a document written by Jafar Tabrizi c. 1430, according to whom: It must be known that nastaʿliq is derived from naskh.

"[7] The picture of origin of nastaliq presented by Elaine Wright was further complicated by studies of Francis Richard, who on the basis of some manuscripts from Tabriz argued that its early evolution was not confined to Shiraz.

It also lacks the definite article al-, whose upright alif and lam are responsible for distinct verticality and rhythm of the text written in Arabic.

The student of Ubaydallah, Jafar Tabrizi (d. 1431) (see quote above), moved to Herat, when he became the head of the scriptorium (kitabkhana) of prince Baysunghur (therefore his epithet Baysunghuri).

The most famous of these calligraphers working for the court in Tabriz was Shah Mahmud Nishapuri (d. 1564/1565), known especially for the unusual choice of nastaliq as a script used for the copy of the Qur'an.

Mirza Mohammad Reza Kalhor (d. 1892), the most important calligrapher of the 19th century, reintroduced the more compact style, writing words on a smaller scale in a single motion.

Another important practitioner of the script was Abd al-Rashid Daylami (d. 1671), nephew and student of Mir Emad, who after his arrival in India became court calligrapher of Shah Jahan (1628–1658).

[20] Its development is connected with the fact that "the increasing use of nastaʿlīq and consequent need to write it quickly exposed it to a process of gradual attrition.

"[4] Shekasteh nastaliq (usually shortened to simply skehasteh), being more easily legible than taliq gradually replaced the latter as the script of decrees and documents.

Both of them produced works of real artistic quality, which does not change the fact that in this early phase shekasteh still lacked consistency (it is especially visible in writing of Mortazaqoli Khan Shamlu).

Most modern scholars consider that shekasteh reached its peak of artistic perfection under Abdol Majid Taleqani (d. 1771), "who gave the script its distinctive and definite form.

[25] The added frills made shekasteh increasingly difficult to read and it remained the script of documents and decrees, "while nastaʿliq retained its pre-eminence as the main calligraphic style."

The need for simplification of shekasteh resulted in development of secretarial style (shekasteh-ye tahriri) by writers like Adib-al-Mamalek Farahani (d. 1917) and Nezam Garrusi (d. 1900).

[27] Although this employed over 20,000 ligatures (individually designed character combinations),[28] it provided accurate results and allowed newspapers such as Pakistan's Daily Jang to use digital typesetting instead of a group of calligraphers.

It suffered from two problems in the 1990s: its non-availability on standard platforms such as Microsoft Windows or Mac OS, and the non-WYSIWYG nature of text entry, whereby the document had to be created by commands in Monotype's proprietary page description language.

The dotted form ڛ is used in place of س .

In print:

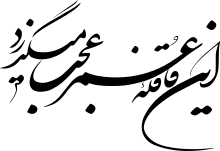

من میگویم که آب انگور خوش است

این نقد بگیر و دست از آن نسیه بدار

کاواز دهل شنیدن از دور خوش است

من میگویم که آب انگور خوش است

این نقد بگیر و دست از آن نسیه بدار

کاواز دهل شنیدن از دور خوش است

In print: