On Passions

A person in the grip of passion has rejected reason, and therapy is a medical art needed to treat the mind.

The treatment outlined by Chrysippus was mostly preventative, demonstrating by theory that the passions are neither natural or necessary, and showing through practice that the mind can be trained to reject them.

[2] Failure to reason correctly brings about the occurrence of pathē—a word translated as passions, emotions, or affections.

[6] The Stoics beginning with Zeno arranged the passions under four headings: distress (lupē), pleasure (hēdonē), fear (phobos) and desire (epithumia).

[7] Under these four headings can be found specific emotions such as anger, longing, envy, grief, and pride.

[12] The wise person who is free from the passions (apatheia) instead experiences good emotions (eupatheia) which are clear-headed feelings.

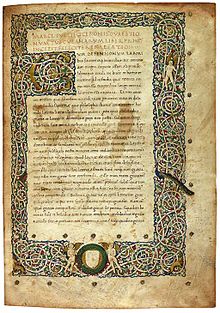

[14] The principal source for the On Passions is the polemical commentary by Galen in his On the Doctrines of Hippocrates and Plato which contains most of the surviving quotations.

[15] The other main source is Cicero's Tusculan Disputations Book IV which contains a discussion of the Stoic passions which is derived from Chrysippus.

[15] A small amount of supplementary information is provided by writers such as Diogenes Laërtius, Stobaeus, Calcidius, and Origen.

[15] Galen quotes Chrysippus' On Passions around seventy times in his On the Doctrines of Hippocrates and Plato, thus preserving up to twenty percent of the text.

[24] Throughout his polemic, Galen draws heavily on the Stoic philosopher Posidonius (1st-century BCE) who wrote his own On Passions as a commentary on Chrysippus.

[28] However, there are no direct quotations from Chrysippus in Cicero's account; he mixes in material drawn from other philosophy schools; and he intersperses his own comments.

[36] Book 4 was known separately as the Therapeutics (Greek: θεραπευτικόν)—a title which apparently goes back to Chrysippus, and it had some status as a stand-alone text.

[39] Zeno had written his own work On Passions which had examined emotions based on common opinions held about them.

The movement of the legs exceeds the impulse, so that they are carried away and do not obediently change their pace the moment they set out to do so.

[46] For the Stoics all bodily processes have a material, corporeal cause,[47] which for Chrysippus as well as Zeno meant physical movements in the soul.

[69] Given this material relationship between body and soul, Chrysippus emphasizes the need for bodily health, and advocates a plain, simple diet.

But if you were to study such events carefully and scientifically, what you would find, quite simply, is that when things happen suddenly, they invariably seem more serious than they otherwise would.

[86] It is the task of therapy to teach that these judgements have a wrong valuation, mistaking indifferent things for good or evil.

[a] Apart from the introduction (§1–10) and the conclusion (§82–84), Tusculan Disputations Book 4 can be divided into three parts, two of which are derived from Chrysippus' On Passions.

Cicero begins (§11) with Zeno's first two definitions of emotion, and moves on to an overview of the four generic passions as well as the three good-feelings attributable to the Stoic Sage (§14).

[89] He follows this (§16–21) with a lengthy catalogue of the emotions arranged under the headings of the four main passions—a list which is again missing from Galen.

[88] After an introduction (§58), Cicero explains (§59–62) the Chrysippean position that one should direct treatment at the passion itself rather than the external cause.

[92] Many of these ideas come from Chrysippus, but Cicero uses examples drawn from Latin poetry instead of the Greek poets.

[92] The therapeutic ideas (§74–75) about introducing distractions or substituting a new lover for an old one are presumably part of Cicero's "Peripatetic" cures.

[94] Cicero's Tusculan Disputations Book 3 is focused on the alleviation of distress rather than the passions generally.

[83] Other Chrysippean passages include a derivation of the word distress (lupē) at §61,[97] and his therapy concerning mourning at §76 and §79.

[26] The influence of Chrysippus on Seneca is clearest in his long essay On Anger (Latin: De Ira).

[109] This includes questioning whether a grand or beautiful passer-by involves something good, or whether a bereaved or hungry person has encountered something bad.

18) on the correct use of impressions, where he explains how diseases grow in the mind in a manner very similar to a Chrysippean passage quoted by Cicero (Tusc.