On the Art of the Cinema

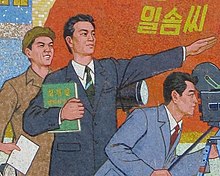

Many ideas presented in the book are justifications for the creation of propaganda supporting the Workers' Party of Korea's policies.

Kim Jong Il gained political and cultural influence in North Korean society and government by authoring the book.

[10] Kim had personally guided the production of films, such as Sea of Blood, (parts one and two, 1969),[10] The Fate of a Self-Defence Corps Man (Korean: 한 자위단원의 운명; MR: Han chawi tanwŏn ŭi unmyŏng,[10] 1970) and The Flower Girl (1972).

[10] He then wrote a series of essays based on speeches he had given to directors and screenwriters over the preceding five years,[12] and published it as On the Art of the Cinema on April 11, 1973.

In the treatise, Kim Jong Il seeks to apply the principles of the North Korean Juche ideology to questions of film, literature and art.

[17][18] The book deals comprehensively with aspects of cinema, including film and literary theory, acting, performance, score music, the screen,[19] camerawork, costumes, make-up, and props.

[7] Ideas in the book are elucidated by drawing examples from North Korean films, of which Sea of Blood is the most referred one.

A key theme of humanics is the question of good and worthy life, allowing for propagandist and moralistic art.

In North Korean literature, Chajusŏng is used as a justification of state control on literary creation[20] and a nationalistic policy of socialism in one country.

[27][b] It has been called a "strange concept", a method of coercing artists to follow the party line, and a means of canceling out individual creativity;[26] Kim Jong Il equates a film with a living organism, noting that in this analogy the seed is its kernel.

[30] For example, the seed of film The Fate of a Self-Defence Corps Man revolves around the choice facing the main character, Gap Ryong: to perish under oppression or sacrificing one's self for the revolution.

[34] In addition to questions of art, the seed theory was adopted to a wider range of industrial and economic activities.

[21] The origins of the speed campaign are in the shooting of The Fate of a Self-Defence Corps Man in just 40 days when it was anticipated to take a full year.

For instance, the eight-part film series Unsung Heroes (1979–1981) was produced by following the speed campaign principle.

[39] While official biographies of Kim Jong Il describe On the Art of the Cinema as comprehensive, original and "supported by impeccable logic",[40] Whitney Mallett calls it boring and repetitive.

According to Johannes Schönherr, the work offers little new to North Korean cinema,[22] and many of the ideas presented are unoriginal and obvious, particularly to the specialist audience of professional filmmakers Kim is writing for.

[43] Instead of contributing anything new, the work reformulates Kim Il Sung's ideas about the importance of film to art and as a propaganda tool.

Rather than the theoretical breakthrough it is taught as, it is an account of Kim Jong Il's personal experiences in the film industry and an attempt to thwart the "sloppiness and thoughtlessness" he had encountered.

[46] Shin and his wife, actress Choi Eun-hee, were kept in North Korea for eight years under cruel conditions.

[46] Kim was delighted with the film and allowed Shin and Choi to travel to Vienna, where they were supposed to negotiate a deal for a sequel.

Australian Anna Broinowski directed Aim High in Creation!, a movie about making a propaganda film abiding by Kim's instructions.

[52] Danish documentarist Mads Brügger in his The Red Chapel is shown continuously consulting the treatise for artistic guidance.

[58] Three speeches that were not included in the English editions – "Some Problems Arising in the Creation of Masterpieces" (1968), "Let Us Create More Revolutionary Films Based on Socialist Life" (1970), and "On the Ideological and Artistic Characteristics of the Masterpiece, The Fate of a Self-Defence Corps Man" (1970) – are included in the Korean edition from 1977.

[6] Translations of On the Art of the Cinema include Arabic, Chinese, English, French, German, Russian and Spanish.