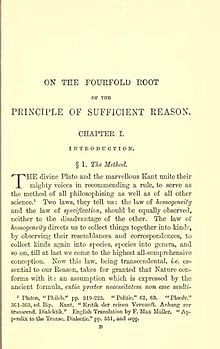

On the Fourfold Root of the Principle of Sufficient Reason

On the Fourfold Root of the Principle of Sufficient Reason (German: Ueber die vierfache Wurzel des Satzes vom zureichenden Grunde) is an elaboration on the classical principle of sufficient reason, written by German philosopher Arthur Schopenhauer as his doctoral dissertation in 1813.

In January 1813, after suffering their disastrous defeat in Russia, the first remnants of Napoleon's Grande Armée were arriving in Berlin.

A patriotic, militaristic spirit inflamed the city and most of the populace, philosophers and students included, entertained the hope that the French yoke could be violently thrown off.

All this rapidly became intolerable to Schopenhauer who ultimately fled the city, retreating to the small town of Rudolstadt near Weimar.

"[1] Among the reasons for the cold reception of this original version are that it lacked the author's later authoritative style and appeared decidedly unclear in its implications.

A copy was sent to Johann Wolfgang von Goethe, who responded by inviting the author to his home on a regular basis, ostensibly to discuss philosophy but in reality to recruit the young philosopher into work on his Theory of Colors.

Schopenhauer proclaimed himself a Kantian who had appropriated his predecessor's most powerful accomplishment in epistemology, and who then claimed to have merely extended and completed what Kant botched or had left undone.

What is crucial here is the realization that what makes human experience universally possible to begin with without exception, is the perceiving mind.

Schopenhauer’s central proposition is the main idea of his entire philosophy, he states simply as “The world is my representation”.

Where a sufficient motive appears in the form either of an intuition, perception, or extracted abstract conception, the subject will act (or react) according to his character, or ‘will.’ e.g., despite all plans to the contrary.

The thing in itself, consequently, remains forever unknowable from any standpoint, for any qualities attributed to it are merely perceived, i.e., constructed in the mind from sensations given in time and space.

This intuition of the a priori understanding is a modern elucidation of the postmodern expression "always already":[9] time and space always and already determine the possibilities of experience.