Johanna Schopenhauer

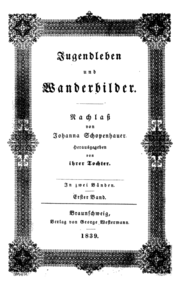

Johanna Schopenhauer (née Trosiener; 9 July 1766 – 17 April 1838) was the first German woman to publish books without a pseudonym, an influential literary salon host, and in the 1820s a popular author in Germany.

Though Johanna did not know of the imminent risk of war, she refused to leave the city when the situation became clear, as transportation was only available to her and her daughter, and her servants would have to be left to their own fate.

[citation needed] After the war, she gained a high reputation as a salonnière (as she had planned before she left Hamburg),[9] and for years to come her semiweekly parties were attended by several literary celebrities: Christoph Martin Wieland, the Schlegel brothers August and Friedrich, Ludwig Tieck, and, above all, Johann Wolfgang von Goethe, whose awareness was probably what attracted Johanna to Weimar in the first place.

In one letter, she wrote: "You are unbearable and burdensome, and very hard to live with; all your good qualities are overshadowed by your conceit, and made useless to the world simply because you cannot restrain your propensity to pick holes in other people.

In 1813, she finally allowed him to move into her house, renting him a room, but the arrangement was soon broken after frequent arguments, motivated by Johanna's friendship with another lodger, a younger man called Georg von Gerstenbergk.

All the communication between the two was from then on through letters, but even this was interrupted after Johanna read a correspondence from Schopenhauer to his sister Adele, where he blamed their mother for the death of their father, understood to have been by suicide, accusing her of going to amuse herself at parties while Heinrich Floris was bedridden, sick and abandoned to the care of a loyal employee.

But this was probably intended not so much to slight her son as in recognition that her daughter would be in greater difficulties in future years, since Arthur not only managed to conserve his part of the fatherly inheritance but even doubled it, whereas Adele would have few resources at her disposal.

[citation needed] In 1837, the Duke, in recognition of Johanna's fame and contribution to the city's culture, offered her a small pension and invited her to move to Jena.

Not long after her arrival in Weimar, Schopenhauer began to publish her writings, consisting of articles on paintings with special attention on Jan van Eyck's work.

The work met with critical success,[citation needed] which encouraged Johanna to pursue a career as an author, on which her livelihood and that of Adele would depend after the aforementioned financial crisis.

Prior to Heinrich Floris' death, the family made trips through Western Europe, mostly in order to help Arthur, then a teenager, develop the skills of a merchant.

[citation needed] In 1990, her travelogue to England and Scotland was translated into English by Chapman & Hall — Johanna's only book to be introduced to the Anglophone world since the turn to the 20th century.