Operation Anaconda

Around the same time, intelligence suggested that Osama bin Laden and the Al-Qaeda leaders had taken refuge in a training camp located in the Tora Bora mountains near Jalalabad, Nangarhar Province in Eastern Afghanistan.

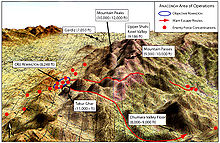

[13] Around mid-January 2002, US officials received intelligence reports indicating that enemy forces, including Al-Qaeda, were gathering in the Shah-i-kot valley in Paktia Province, which was located about 60 miles south of Gardez.

[23] The signal intelligence also raised the possibility that high-value targets (HVTs) were present in the valley among which were not only Saif Rehman, but also Tohir Yuldeshev, co-founder of the terrorist organization Islamic Movement of Uzbekistan, and Jalaluddin Haqqani, whose tribal network controlled the area.

The operation officer of Task Force Dagger, Mark Rosengard, explained why they chose to rely on the Afghan militias that had previously disappointed them during the Battle of Tora Bora.

Even extensive satellite imagery of the Shah-i-Kot area didn't reveal much because the Al-Qaeda forces there were too lightly equipped and too adept at camouflage to stand out, unlike the easily recognizable Iraqi tank brigades in the First Gulf War.

All three teams were tasked with confirming enemy strengths and dispositions including antiaircraft emplacements, ensuring the designated Rakkasan helicopter landing zones were clear of obstructions, and providing terminal guidance for air support both prior to and during the insertion of conventional forces.

Task Force Hammer, led by Commander Zia Lodin with 500 Afghan Pashtun units, would enter the valley through the northern entrance in a ground assault convoy.

The intense small arms and mortar fire, combined with the absence of close air support, caused the Afghan forces of TF Hammer to scatter and refuse to advance any further.

[47][48] At 06:30 the first wave of Rakkasans and Mountain troops landed via Chinook helicopter along the eastern and northern edges of the valley to await the fleeing fighters at their assigned blocking positions.

Blaber insisted that this was a once-in-a-lifetime opportunity on the battlefield and that he intended to keep his teams in the Shah-i-Kot Valley, continuing to decimate the enemy through air strikes until they were no longer a threat.

In this engagement, Staff Sergeant Andrzej Ropel, and Specialist William Geraci, recently transferred in from the Division's Long Range Surveillance Detachment, led the squad under fire to a ridgeline above the "Halfpipe."

Lieutenant Colonel Ron Corkran's 187th Infantry Battalion arrived in the northern region around 8:00 PM on March 3 and began their careful sweep southward, encountering no resistance.

Not only were these robust aircraft far less susceptible to ground fire, but they could also remain over the battlefield during daylight hours and deliver accurate strikes without requiring the assistance of Air Force tactical controllers.

[60] Around this time command decided to change the frequencies for satellite radio communications which different units, including the AFO teams in their reconnaissance positions, were relying on to conduct and adapt the mission as the battle unfolded.

[citation needed] Though the change may have been meant to enhance direct control of the rescue of the downed SEAL atop Takur Ghar, it had the critical effect of severely limiting communications between the different teams participating in the battle.

The surviving crew and quick-reaction force at first attempted a daring assault on the Taliban positions but faced tough resistance from concealed insurgent bunkers, which caused the Rangers to retreat and take cover in a hillock where a fierce firefight began.

Hyder directed the Chalk 2 leader to continue mission up the mountain and moved, alone, to link up with Mako 21 in order to assist that team's movement away from the peak thereby creating a better situation for air assets to support by fire.

Through threat of nearby enemy response elements, hypothermia and shock of wounded personnel, and across nearly 30" of snow in extreme terrain, Mako 21 found a site suitable for an MH-47.

They remained undetected in an observation post through the firefight and proved critical in co-ordinating multiple Coalition air strikes to prevent the al-Qaeda fighters from overrunning the downed aircraft, to devastating effect.

Australian soldiers had utilised 'virtual reality' style software for mission rehearsal prior to insertion, and this contributed significantly to their situational awareness in the darkness and poor weather conditions.

Supported by 16 Apaches, 5 USMC Cobras helicopters and several A-10A ground attack aircraft; the Rakkasans methodically cleared an estimated 130 caves, 22 bunkers and 40 buildings to finally secure the valley.

Major General Frank Hagenbeck did confirm that al-Qaeda fighters were seen (on live video feed from a Predator drone orbiting the firefight) chasing Roberts, and later dragging his body away from the spot where he fell.

"[29] Predator drone footage also suggested the possibility that Technical Sergeant John Chapman was alive and fighting on the peak after the SEALs left rather than being killed outright as thought by Mako 30.

Zia Lodin, a Pashtun commander, held distinct differences from Gul Haidar, a Tajik from Logar Province, who served as the Afghan defense minister and had a background with the Northern Alliance.

Task Force 11 received time-sensitive intelligence that a possible high-value target was traveling within a convoy of al-Qaeda fighters who were attempting to escape by vehicle from Shah-i-Kot into Pakistan.

The operators recovered a lot of US military equipment: a US-made suppressor, a number of US fragmentation grenades issued to TF 11 and a Garmin handheld GPS, later traced to the crew of Razor 01.

"[74] Investigative reporter Seymour Hersh refuted the official account, describing it as "in fact a debacle, plagued by squabbling between the services, bad military planning and avoidable deaths of American soldiers, as well as the escape of key al-Qaeda leaders, likely including Osama bin Laden.

The U.S. forces estimated they had killed at least 500 fighters over the duration of the battle, however, journalists later noted that only 23 bodies were found – and critics suggested that after a couple of days, the operation "was more driven by media obsession, than military necessity".

"[citation needed] Relations were further soured with reports from a number of publications that Osama bin Laden might have escaped due to a substantial delay from the original H-hour of the deployment of American Forces.

[81] The 10th Mountain Division carried out intelligence-driven operations to locate any remaining Al-Qaeda and Taliban insurgents but did not find much, as it appeared that the jihadists had either escaped to Pakistan or gone into hiding in remote areas of Afghanistan.