Bombing of Tokyo (10 March 1945)

On the night of 9/10 March 1945, the United States Army Air Forces (USAAF) conducted a devastating firebombing raid on Tokyo, the Japanese capital city.

More than 90,000 and possibly over 100,000 Japanese people were killed, mostly civilians, and one million were left homeless, making it the most destructive single air attack in human history.

The USAAF units employed significantly different tactics from those used in precision raids, including bombing by night with the aircraft flying at low altitudes.

[3] The British Bomber Command focused on destroying German cities from early 1942 until the end of the war, and incendiaries represented 21 percent of the tonnage of bombs its aircraft dropped.

[9] The first Superfortress flight over Tokyo took place on 1 November, when a reconnaissance aircraft photographed industrial facilities and urban areas in the western districts of the city.

[9] Arnold and the Twentieth Air Force's headquarters regarded the campaign against Japan up to that time as unsuccessful, and LeMay understood that he would also be relieved if he failed to deliver results.

Japan's main industrial facilities were vulnerable to such attacks as they were concentrated in several large cities, and a high proportion of production took place in homes and small factories in urban areas.

The planners estimated that incendiary bomb attacks on Japan's six largest cities could cause physical damage to almost 40 percent of industrial facilities and result in the loss of 7.6 million man-months of labor.

[31][32] The failure of a precision bombing attack on an aircraft factory in Tokyo on 4 March marked the end of the period in which XXI Bomber Command primarily conducted such raids.

[34][35] In early March, LeMay judged that further precision bombing of Japanese industrial targets was unlikely to be successful due to the prevailing weather conditions over the country.

[57] Due to shortages of radar and other fire control equipment, Japanese anti-aircraft gunners found it difficult to target aircraft operating at night.

[72] The orders for the raid issued to the B-29 crews stated that the main purpose of the attack was to destroy the many small factories located within the target area, but also noted that it was intended to cause civilian casualties as a means of disrupting production at major industrial facilities.

[44] The B-29s in the squadrons which were scheduled to arrive over Tokyo first were armed with M47 bombs; these weapons used napalm and were capable of starting fires which required mechanized firefighting equipment to control.

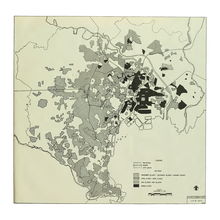

Each of XXI Bomber Command's wings and their subordinate groups had been briefed to attack different areas within the X shape to ensure that the raid caused widespread damage.

Subsequent sightings of B-29s flying at low levels were not taken seriously, and the Japanese radar stations focused on searching for American aircraft operating at their usual high altitudes.

[97] One of the most deadly incidents occurred when the full bomb load of a B-29 landed in a crowd of civilians crossing the Kototoi Bridge over the Sumida River, causing hundreds of people to be burned to death.

Many of those who attempted to evacuate to the large parks which had been created as refuges against fires following the 1923 Great Kantō earthquake were killed when the conflagration moved across these open spaces.

[110] In one instance, over a thousand people were killed after they took refuge in a school's massive swimming pool and were subsequently boiled alive as the water turned to steam.

[122][123] LeMay and Arnold considered the operation to have been a significant success on the basis of reports made by the airmen involved and the extensive damage shown in photographs taken by reconnaissance aircraft on 10 March.

[128] For instance, both Arnold and LeMay regarded the 10 March raid and subsequent firebombing operations as being necessary to save American lives by bringing the war to a rapid conclusion.

[136] In a break from the usual practice of downplaying the damage caused by air attacks, the Japanese Government encouraged the media to emphasize the extensive scale of the destruction in an attempt to motivate anger against the United States.

[141] The attack considerably damaged the morale of Japanese civilians, with it and the other firebombing raids in March convincing most that the war situation was worse than their government had admitted.

The Japanese Government responded with a combination of repression, including heavy penalties for people accused of disloyalty or spreading rumors, and a propaganda campaign focused on restoring confidence in the country's air and civil defense measures.

[93] From April, the Japanese reduced their attempts to intercept Allied air raids to preserve aircraft to contest the expected invasion of Japan.

From 11 May until the end of the war the B-29s conducted day precision bombing attacks when weather conditions were favorable, and night firebombing raids against cities at all other times.

Karacas argues that the Japanese Government prefers to focus on the atomic bombing of Hiroshima and Nagasaki as commemoration of these attacks "reinforces the Japanese-as-victim stereotype".

[157] In 2007 a group of survivors of the 10 March raid and bereaved families launched a lawsuit seeking compensation and an apology for the Japanese Government's actions regarding the attack.

For instance, the USAAF official history judged that the attack fully met LeMay's objectives, and it and the subsequent firebombing raids shortened the war.

[163] Historians such as Biddle, William W. Ralph and Barrett Tillman have argued that the decision to change to firebombing tactics was motivated by Arnold and LeMay's desire to prove that the B-29s were effective, and that a strategic bombing force could be a war-winning military arm.

[171] Some commentators believe that racism motivated the decision to use firebombing tactics, in contrast to the USAAF's greater emphasis on precision bombing in its air campaign against Germany.