Operation Ripper

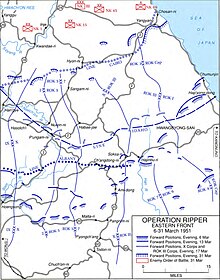

Following the recapture of Seoul the PVA/KPA forces retreated northward, conducting skilful delaying actions that utilized the rugged, muddy terrain to maximum advantage, particularly in the mountainous US X Corps sector.

As Operation Killer had entered its final week with limited results already predictable, Ridgway published plans for another attack, again with the main effort in his central zone, but with all units on the Eighth Army front involved.

The shortages resulted partially from conscious efforts during February, especially during the Chinese Fourth Phase Offensive in mid-February, to hold down stockpiles in forward dumps as a hedge against losses through forced abandonment or destruction.

In addition, as stocks were expended in the Killer advance, the damage to roads, rail lines, bridges, and tunnels caused by the rains and melting ice and snow severely hampered resupply.

[3]: 311 Regardless of success in meeting this logistical requirement, Ridgway intended to cancel the operation if in the time taken to raise forward supply levels new intelligence disclosed clear evidence of an imminent PVA/KPA attack.

Eighth Army intelligence officer Colonel Tarkenton, believed these forces would tie in with the existing PVA/KPA front tracing the north bank of the Han River in the west and passing through the ridges above Route 20 in the east.

During interrogation, recently taken prisoners of war partially substantiated the agent reports by stating that their forces were preparing to launch an offensive in the Eighth Army's central zone early in March.

[3]: 311–313 Amid efforts to acquire fuller information on PVA/KPA preparations and plans, Ridgway arranged an amphibious demonstration in the Yellow Sea in an attempt to fix PVA/KPA reserves and to distract their attention from the central zone in which the main Ripper attack was to be made.

In laying out this campaign FEAF commander General George E. Stratemeyer had emphasized attacks on the rail net since its capacity for troop and supply movements was much greater than that of the roads; he had stressed in particular the destruction of railroad bridges.

But as the attacks continued, a principal point in the selection of targets remained that dropping the railroad bridges and keeping them unserviceable would leave the PVA/KPA with no usable stretch of rail line more than 30 miles (48 km) long.

Since Line Idaho traced a deep salient into PVA/KPA territory, a successful advance to it would carry the Eighth Army, in particular IX Corps in the center, into an area believed to hold a large concentration of PVA/KPA forces and supplies.

East of Seoul on the Corps' right, the US 25th Infantry Division, now commanded by Brigadier general Joseph S. Bradley, was to attack across the Han on both sides of its confluence with the southward flowing Pukhan River.

Above the Han, Bradley's division was to clear the high ground bordering the Pukhan to protect the left flank of IX Corps and to threaten envelopment of PVA/KPA forces defending Seoul.

Joined quickly by tanks that forded or were ferried across the river, and helped by good close air support after daybreak, the assault battalions pushed through moderate resistance, much of it in the form of small arms, machine gun, and mortar fire and a profusion of well placed antitank and antipersonnel mines, for first-day gains of 1–2 miles (1.6–3.2 km).

[3]: 323 What the intelligence staff had reported in mid-February as the entry of seven new PVA armies into Korea was largely the return of the three KPA corps and nine divisions that had withdrawn into Manchuria for reorganization and retraining the past autumn.

Avoiding Route 1 in favor of lesser roads nearby, Corps' commander Lieurenant general Choe Yong Jin took his divisions south into Hwanghae Province and assembled them in the Namch’onjom-Yonan area northwest of Seoul.

Crossing the Yalu at Sinuiju in January, VII Corps, with the 13th, 32nd and 37th Divisions, proceeded across Korea in a drawn out series of independent movements by subordinate units to the Wonsan area, closing there by the end of February.

Since that time, under the command of Lieutenant general Pak Chong Kok and operating with the 4th, 5th and 105th Tank Divisions and the 26th Brigade, the IV Corps had had the mission of defending the Yellow Sea coast between Chinnamp’o and Sinanju.

Now in command was Lieutenant general Kim Ung, who during World War II had served with the Chinese 8th Route Army in north China and more recently had led the KPA I Corps in the main attack during the initial invasion of South Korea.

The movement and positioning of reinforcements from Manchuria would continue through most of March; the remainder of the IX Army Group would not be fully ready to move south until the turn of the month; and the refurbishing of other units, both North Korean and Chinese, would require even more time.

[3]: 326–7 In ordering the second phase of Ripper to begin, Ridgway allowed for the possibility that the PVA would set up stout defenses in the ground immediately below Hongcheon and instructed the IX Corps' commander to take the town by double envelopment, not by frontal assault.

Long range small-arms fire and small, scattered groups of PVA who made no genuine attempt to delay the advance toward Hongcheon were the extent of the opposition the 1st Cavalry and 1st Marine Divisions encountered during the morning.

On the return trip, following an explosion that damaged a truck, the patrol discovered that FEAF bombers had liberally sprinkled the eastern half of the town with small bombs set to explode when disturbed.

The first sign appeared on 12 March when aerial observers flying over the PVA/KPA's Han River positions between Seoul and the 25th Division's bridgehead saw a large number of troops moving northwest out of that area.

Nearer the city, another patrol moved as far north as the Seoul-Chuncheon road without contact; a third found that Hill 175, one of the lower peaks of South Mountain hugging Seoul at its southeast edge, also was vacant.

Ridgway left it to Milburn to decide the strength of the forces who would cross the river, but restricted their forward movement, once they were on the Lincoln Line, to patrolling to the north and northwest to regain contact.

Soon after Seoul was reoccupied, therefore, a concerted, but not entirely successful effort, began via the press, radio, and police lines to prevent former residents from returning to the city while it was made livable again and while local government was restored under the guidance of civil assistance teams and ROK officials.

Much as anticipated, the Marines on the right and the ROK on the left met negligible resistance while the 1st Cavalry Division in the center received heavy fire and several sharp counterattacks in a daylong fight for dominating heights just above the Hongcheon River.

[3]: 332 During this search to the northeast a second task force from the cavalry division reached Chuncheon in midafternoon, just in time to greet Ridgway, who, after observing operations from a light plane overhead, landed on one of the town's longer streets.

Searching to confirm this information, Ridgway on 18 March ordered all three corps on the eastern front to reconnoiter deep beyond the parallel in the area between the Hwach’on Reservoir, located almost due north of Chuncheon, and the east coast.