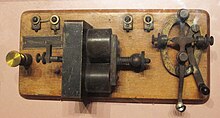

Telegraph key

The straight keys also had a shorting bar that closed the electrical circuit through the station when the operator was not actively sending messages.

The shorting switch for an unused key was needed in telegraph systems wired in the style of North American railroads, in which the signal power was supplied from batteries only in telegraph offices at one or both ends of a line, rather than each station having its own bank of batteries, which was often used in Europe.

Although occasionally included in later keys for reasons of tradition, the shorting bar is unnecessary for radio telegraphy, except as a convenience to produce a steady signal for tuning the transmitter.

The straight key is simple and reliable, but the rapid pumping action needed to send a string of dots (or dits as most operators call them) poses some medically significant drawbacks.

[5] "Glass arm" may be reduced or eliminated by increasing the side play of the straight key, by loosening the adjustable trunnion screws.

The keyer may be either an independent device that attaches to the transmitter in place of a telegraph key, or circuitry incorporated in modern amateurs' radios.

This key uses a side-to-side action with contacts on both the left and right and the arm spring-loaded to return to center; the operator may make a dit or dah by swinging the lever in either direction.

This first new style of key was introduced in part to increase speed of sending, but more importantly to reduce the repetitive strain injury affecting telegraphers.

A skilled operator can achieve sending speeds in excess of 40 words per minute with a ‘bug’.

The benefit of the clockwork mechanism is that it reduces the motion required from the telegrapher's hand, which provides greater speed of sending, and it produces uniformly timed dits (dots, or short pulses) and maintains constant rhythm; consistent timing and rhythm are crucial for decoding the signal on the other end of the telegraph line.

Most electronic keyers include dot and dash memory functions, so the operator does not need to use perfect spacing between dits and dahs or vice versa.

With a dual paddle both contacts may be closed simultaneously, enabling the "iambic"[b] functions of an electronic keyer that is designed to support them: By pressing both paddles (squeezing the levers together) the operator can create a series of alternating dits and dahs, analogous to a sequence of iambs in poetry.

But any single- or dual-paddle key can be used non-iambicly, without squeezing, and there were electronic keyers made which did not have iambic functions.

The efficiency of iambic keying has recently been discussed in terms of movements per character and timings for high speed CW, with the author concluding that the timing difficulties of correctly operating a keyer iambicly at high speed outweigh any small benefits.

In the Ultimatic keying mode, the keyer will switch to the opposite element if the second lever is pressed before the first is released (that is, squeezed).

Starting in the 1940s, initiated by B. F. Skinner at Harvard University, the keys were mounted vertically behind a small circular hole about the height of a pigeon's beak in the front wall of an operant conditioning chamber.

Electromechanical recording equipment detected the closing of the switch whenever the pigeon pecked the key.

With straight keys, side-swipers, and, to an extent, bugs, each and every telegrapher has their own unique style or rhythm pattern when transmitting a message.

This had a huge significance during the first and second World Wars, since the on-board telegrapher's "fist" could be used to track individual ships and submarines, and for traffic analysis.

Only inter-character and inter-word spacing remain unique to the operator, and can produce a less clear semblance of a "fist".