Pendulum

In the case of a typical grandfather clock whose pendulum has a swing of 6° and thus an amplitude of 3° (0.05 radians), the difference between the true period and the small angle approximation (1) amounts to about 15 seconds per day.

[20] Released by a lever, a small ball would fall out of the urn-shaped device into one of eight metal toads' mouths below, at the eight points of the compass, signifying the direction the earthquake was located.

[20] Many sources[21][22][23][24] claim that the 10th-century Egyptian astronomer Ibn Yunus used a pendulum for time measurement, but this was an error that originated in 1684 with the British historian Edward Bernard.

The earliest extant report of his experimental research is contained in a letter to Guido Ubaldo dal Monte, from Padua, dated November 29, 1602.

[33] His biographer and student, Vincenzo Viviani, claimed his interest had been sparked around 1582 by the swinging motion of a chandelier in Pisa Cathedral.

[46][47] In 1687, Isaac Newton in Principia Mathematica showed that this was because the Earth was not a true sphere but slightly oblate (flattened at the poles) from the effect of centrifugal force due to its rotation, causing gravity to increase with latitude.

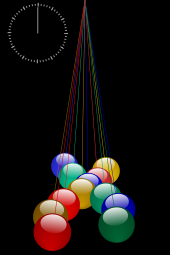

In 1851, Jean Bernard Léon Foucault showed that the plane of oscillation of a pendulum, like a gyroscope, tends to stay constant regardless of the motion of the pivot, and that this could be used to demonstrate the rotation of the Earth.

[65][66] Around 1900 low-thermal-expansion materials began to be used for pendulum rods in the highest precision clocks and other instruments, first invar, a nickel steel alloy, and later fused quartz, which made temperature compensation trivial.

[8][80] During operation, any elasticity will allow tiny imperceptible swaying motions of the support, which disturbs the clock's period, resulting in error.

[83] This was discovered when people noticed that pendulum clocks ran slower in summer, by as much as a minute per week[60][84] (one of the first was Godefroy Wendelin, as reported by Huygens in 1658).

By using the correct height of mercury in the container these two effects will cancel, leaving the pendulum's centre of mass, and its period, unchanged with temperature.

Around 1900, low thermal expansion materials were developed which could be used as pendulum rods in order to make elaborate temperature compensation unnecessary.

Even moving a pendulum clock to the top of a tall building can cause it to lose measurable time from the reduction in gravity.

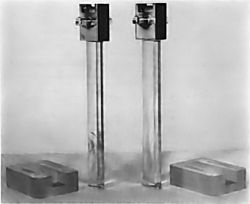

Precision pendulums are suspended on low friction pivots consisting of triangular shaped 'knife' edges resting on agate plates.

[2][101] Pendulums (unlike, for example, quartz crystals) have a low enough Q that the disturbance caused by the impulses to keep them moving is generally the limiting factor on their timekeeping accuracy.

[114] To get around this problem, the early researchers above approximated an ideal simple pendulum as closely as possible by using a metal sphere suspended by a light wire or cord.

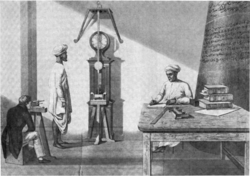

Kater built a reversible pendulum (see drawing) consisting of a brass bar with two opposing pivots made of short triangular "knife" blades (a) near either end.

After applying corrections for the finite amplitude of swing, the buoyancy of the bob, the barometric pressure and altitude, and temperature, he obtained a value of 39.13929 inches for the seconds pendulum at London, in vacuum, at sea level, at 62 °F.

These were vulnerable to damage or destruction over the years, and because of the difficulty of comparing prototypes, the same unit often had different lengths in distant towns, creating opportunities for fraud.

Gravitational acceleration increases smoothly from the equator to the poles, due to the oblate shape of the Earth, so at any given latitude (east–west line), gravity was constant enough that the length of a seconds pendulum was the same within the measurement capability of the 18th century.

For example, a pendulum standard defined at 45° north latitude, a popular choice, could be measured in parts of France, Italy, Croatia, Serbia, Romania, Russia, Kazakhstan, China, Mongolia, the United States and Canada.

The idea of a pendulum standard of length must have been familiar to people as early as 1663, because Samuel Butler satirizes it in Hudibras:[131] In 1671 Jean Picard proposed a pendulum-defined 'universal foot' in his influential Mesure de la Terre.

A plan for a complete system of units based on the pendulum was advanced in 1675 by Italian polymath Tito Livio Burratini.

It was advocated by a group led by French politician Talleyrand and mathematician Antoine Nicolas Caritat de Condorcet.

A possible additional reason is that the radical French Academy didn't want to base their new system on the second, a traditional and nondecimal unit from the ancien regime.

In 1821 the Danish inch was defined as 1/38 of the length of the mean solar seconds pendulum at 45° latitude at the meridian of Skagen, at sea level, in vacuum.

This principle, called Schuler tuning, is used in inertial guidance systems in ships and aircraft that operate on the surface of the Earth.

The allegation is contained in the 1826 book The history of the Inquisition of Spain by the Spanish priest, historian and liberal activist Juan Antonio Llorente.

[148] This method of torture came to popular consciousness through the 1842 short story "The Pit and the Pendulum" by American author Edgar Allan Poe.

[150][151][152] The only evidence of its use is one paragraph in the preface to Llorente's 1826 History,[147] relating a second-hand account by a single prisoner released from the Inquisition's Madrid dungeon in 1820, who purportedly described the pendulum torture method.

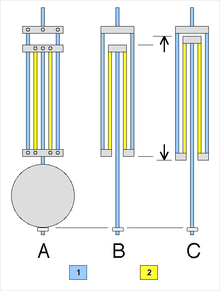

- exterior schematic

- normal temperature

- higher temperature