Optical glass

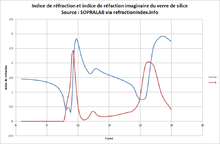

Lenses produced for optical applications use a wide variety of materials, from silica and conventional borosilicates to elements such as germanium and fluorite, some of which are essential for glass transparency in areas other than the visible spectrum.

The earliest known optical lenses, dating from before 700 BC, were produced under the Assyrian Empire:[2] they were made of polished crystals, usually quartz, rather than glass.

[3] Although the exact date of their invention is not known, glasses are said to have been described in 1299 by Sandro di Popozo in his Treatise on Family Conduct: "I am so altered by age, that without these lenses called spectacles, I would no longer be able to read or write.

Thus, the first complex optical instruments, such as Galileo's telescope (1609), used ordinary soda-lime glass (the first crown glass), composed of sand, soda, potash and sometimes lime, which, although suitable for glazing or bottles, was hardly suitable for optical applications (distortion, blurred effect, irregularities, etc.).

[5] Chester Moore Hall (1703-1771), using the two types of glass available (soda-lime crown and lead flint), invented the first achromatic doublet.

As optics became increasingly complex and diverse, manufacturers' catalogs expanded to include 100 to 200 different lenses; glass melts increasingly included special components such as oxides of heavy elements (high refractive index and low dispersion), chalcogenides (sulfide, selenide, telluride), halides such as fluorides (low refractive index and high dispersion) or phosphides, cerium-doped glasses to obtain radiation-resistant lenses, and so on.

Chalcogenide glasses have indexes exceeding 2, a large proportion of which cannot be shown on an Abbe diagram due to their absorption in visible wavelengths preventing a relevant νd measurement.

The use to which the future lens will be put determines its behavior: filters that absorb in certain spectral bands, lenses that are highly transparent in the visible, ultraviolet or infrared, resistance to radiation.

There are two types of oxygen in oxide glasses: bridging and non-bridging (possessing an excess electron charge), detectable by photoelectron spectroscopy.

[15] Depending on the intensity of the bonds with the cations in the glass, the transmission window varies: in the presence of alkali metals, electrons can move from one band to the other more easily, as they are less bound to the non-bridging oxygens.

It has been found that in this high illumination range, the refractive index follows a law that deviates from the linear domain and becomes proportional to the intensity of the luminous flux:

Above TW mm−2, the fluence (or flux) is sufficient to create higher-order non-linear optical phenomena such as multiphonon absorption and avalanche photo-ionization.

The energy of the incident light excites the material's electrons, which then de-excite and return to their ground state, emitting a photon with a longer wavelength than the original one.

[19] The basic materials used to manufacture optical lenses must be particularly pure, as any inclusion or impurity could not only degrade performance but also cause considerable damage to the lens (breakage, darkening, tinting, etc.).

[21] The glassmaking process comprises a number of stages, beginning with the melting of the glass paste, followed by refining and then tempering or annealing, which are two different finishes.

Finally, if required, the glass can be polished, particularly in the case of mirrors and lenses, for any application where the objective is high image quality.

[22] Refining is an essential stage in the quality of optical lenses, since it involves homogenizing the glass so that the components are evenly distributed throughout the paste and the gas is fully released.

Alkali oxides and boron trioxide B2O3 make it easier to melt silicon dioxide SiO2, which requires very high temperatures to liquefy.

[28] Dense or light flints are long-established families, such as borosilicate crowns, and are used as optical glass as well as crystal for everyday glassmaking.

Barium flints crystallize less easily than other glass families due to the presence of lead(II) oxide (PbO) in the mixture.

The use of SiO2 in the paste creates crystallization instabilities, a pitfall avoided by replacing silica with boron trioxide B2O3 and divalent oxides.

Their transmission covers the visible and mid-infrared range, from 200 nm to 7 μm, due to the rather high band gap (on average, a fluoride glass has its transmission dip at around 250 nm, due to its band gap of around 5 eV)[26] and the low-frequency vibrations of the heavy-metal fluoride bonds; silica absorption results from vibrations of Si-O bonds at 1.1 × 103 cm−1, whereas fluorozirconate absorption will result from vibrations of Zr-F bonds at a frequency of 0.58 × 103 cm−1, which is why oxide and halide glasses behave so differently in the infrared.

Their index is greater than 2, and they appear black due to their weak gap and multiple absorption bands in the visible range.

The former are mainly composed of germanium and gallium sulfides and selenides, while the latter, although not doped, offer the best transmission performance in the far infrared.

Its main properties are low expansion (α≈0.5 × 10−6 K−1),[31] high thermal stability (up to 1,000 K)[31] and transmission in the ultraviolet and infrared, which can be adapted as required.

In 1854, James Clerk Maxwell invented the "Fisheye lens" in response to a problem from the Irish Academy asking for the refractive index of an image-perfect material.

For larger gradients, there is partial lens polymerization of a monomer reacting to UV exposure (gradients of around one hundred millimeters for an index amplitude of 0, 01), or superimposing and then partially melting layers of borosilicate or flint glass (lanthanum-containing glasses are not suitable for this technique due to their recrystallization problems and thermal instability).

[37] Certain extreme environments are not conducive to the use of conventional lenses; when the system is exposed to far-field UV radiation (X, gamma, etc.)

or particle fluxes such as alpha or beta, a drop in lens transmission is observed, due to discoloration of the material.

These effects can easily be amplified by the presence of impurities that change the valence of molecules or concentrate radiation, causing local degradation of the glass.