Optical mapping

Originally developed by Dr. David C. Schwartz and his lab at NYU in the 1990s [2] this method has since been integral to the assembly process of many large-scale sequencing projects for both microbial and eukaryotic genomes.

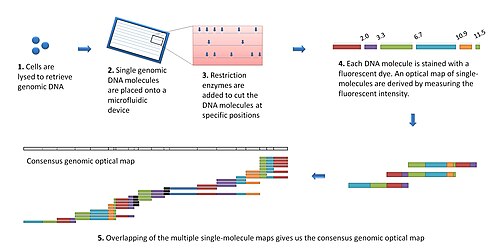

The modern optical mapping platform works as follows:[7] DNA molecules were fixed on molten agarose developed between a cover slip and a microscope slide.

Restriction enzyme was pre-mixed with the molten agarose before DNA placement and cleavage was triggered by addition of magnesium.

Rather than being immobilized within a gel matrix, DNA molecules were held in place by electrostatic interactions on a positively charged surface.

This involved the development and integration of an automated spotting system to spot multiple single molecules on a slide (like a microarray) for parallel enzymatic processing, automated fluorescence microscopy for image acquisition, image procession vision to handle images, algorithms for optical map construction, cluster computing for processing large amounts of data Observing that microarrays spotted with single molecules did not work well for large genomic DNA molecules, microfluidic devices using soft lithography possessing a series of parallel microchannels were developed.

An improvement on optical mapping, called "Nanocoding",[8] has potential to boost throughput by trapping elongated DNA molecules in nanoconfinements.

In addition, since maps are constructed directly from genomic DNA molecules, cloning or PCR artifacts are avoided.

For larger eukaryotic genomes, only the David C. Schwartz lab (now at Madison-Wisconsin) has produced optical maps for mouse,[14] human,[15] rice,[16] and maize.

These molecules are then barcoded by restriction enzymes to allow for genomic localization through the technique of optical mapping.