Optimal foraging theory

Optimal foraging theory (OFT) is a behavioral ecology model that helps predict how an animal behaves when searching for food.

[1] When using OFT to model foraging behavior, organisms are said to be maximizing a variable known as the currency, such as the most food per unit time.

Studies on optimal foraging behaviors at the population level have utilized evolutionary birth-death dynamics models.

While these models confirm the existence of objective functions, such as "currency" in certain scenarios, they also prompt questions regarding their applicability in other limits such as high population interactions.

[2] In this model, the currency is energy intake per unit time and the constraints include the actual values of E, h, and S, as well as the fact that prey items are encountered sequentially.

[13] In general, different animals across the four functional classes of predators exhibit strategies ranging across a continuum between being a generalist and a specialist.

[15] For a Type II functional response curve, the rate of prey capture negatively accelerates as it increases with food density.

[14] Predator–prey coevolution often makes it unfavorable for a predator to consume certain prey items, since many anti-predator defenses increase handling time.

[16] Examples include porcupine quills, the palatability and digestibility of the poison dart frog, crypsis, and other predator avoidance behaviors.

Thus, it is possible that an approach focusing only on energy intake may not fully explain an animal's foraging behavior in these situations.

This theorem is used to describe a situation in which an organism searching for food in a patch must decide when it is economically favorable to leave.

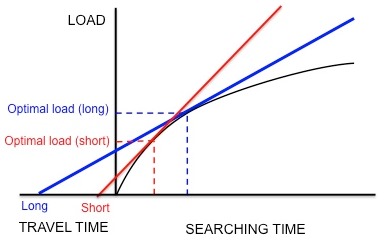

[5] This law of diminishing returns can be shown as a curve of energy gain per time spent in a patch (Figure 3).

The place that this line touches the curve provides the optimal decision rule of the amount of time that the animal should spend in a patch before leaving.

Starlings leave their nests and travel to food patches in search for larval leatherjackets to bring back to their young.

[5] Using this currency and the constraints, the optimal load can be predicted by drawing a line tangent to the curve of diminishing returns, as discussed previously (Figure 3).

Kacelnik et al. wanted to determine if this species does indeed optimize net energy gain per unit time as hypothesized.

In agreement with these predictions, Kacelnik found that the longer the distance between the nest and the artificial feeder, the larger the load size.

[19][20] Worker bees provide another example of the use of marginal value theorem in modeling optimal foraging behavior.

Thus, there is a curve of diminishing returns for the net yield of energy that the hive receives as the bee gathers more nectar during one trip.

This is because the optimal load predicted by maximizing net rate of energy gain is too heavy for the bees and shortens their lifespan, decreasing their overall productivity for the hive, as explained earlier.

[22] The nature of prey selection by two centrarchids (white crappie and bluegill) has been presented as a model incorporating optimal foraging strategies by Manatunge and Asaeda.

[23] The visual field of the foraging fish as represented by the reactive distance was analysed in detail to estimate the number of prey encounters per search bout.

The energetic cost associated with fish foraging behaviour was calculated based on the sequence of events that takes place for each prey consumed.

In most cases, the fish exclusively selected large Daphnia, ignoring evasive prey types (Cyclops, diaptomids) and small cladocera.

Although many studies, such as the ones cited in the examples above, provide quantitative support for optimal foraging theory and demonstrate its usefulness, the model has received criticism regarding its validity and limitations.

Given that genetics involves interactions between loci, recombination, and other complexities, there is no guarantee that natural selection can optimize a specific behavioral parameter.

However, in reality, it is difficult to define basic concepts like prey type, encounter rates, or even a patch as the forager perceives them.

[24] Without accounting for this possibility, many studies using the OFT remain incomplete and fail to address and test the main point of the theory.

[24] This creates the problem of researchers shaping their model to fit their observations, rather than rigorously testing their hypotheses about the animal's foraging behavior.

Foraging strategy must provide the most benefit for the lowest cost – it is a balance between nutritional value and energy required.