Oral rehydration therapy

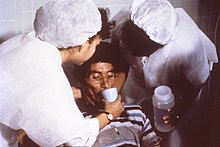

Oral rehydration therapy (ORT) is a type of fluid replacement used to prevent and treat dehydration, especially due to diarrhea.

[1] Therapy can include the use of zinc supplements to reduce the duration of diarrhea in infants and children under the age of 5.

[2] Oral rehydration therapy was developed in the 1940s using electrolyte solutions with or without glucose on an empirical basis chiefly for mild or convalescent patients, but did not come into common use for rehydration and maintenance therapy until after the discovery that glucose promoted sodium and water absorption during cholera in the 1960s.

People who have severe dehydration should seek professional medical help immediately and receive intravenous rehydration as soon as possible to rapidly replenish fluid volume in the body.

[20] The Rehydration Project states, "Making the mixture a little diluted (with more than 1 litre of clean water) is not harmful.

[23] A Lancet review in 2013 emphasized the need for more research on appropriate home made fluids to prevent dehydration.

This recommendation was based on multiple clinical trials showing that the reduced osmolarity solution reduces stool volume in children with diarrhea by about twenty-five percent and the need for IV therapy by about thirty percent when compared to standard oral rehydration solution.

[31] Clinical trials have, however, shown reduced osmolarity solution to be effective for adults and children with cholera.

[30] ORT is based on evidence that water continues to be absorbed from the gastrointestinal tract even while fluid is lost through diarrhea or vomiting.

Older children and adults should take frequent sips from a cup, with a recommended intake of 200–400 mL of solution after every loose movement.

[35] After severe dehydration is corrected and appetite returns, feeding the person speeds the recovery of normal intestinal function, minimizes weight loss and supports continued growth in children.

The IV route should not be used for rehydration except in cases of shock and then only with care, infusing slowly to avoid flooding the circulation and overloading the heart.

A child who cannot or will not eat this minimum amount should be given the diet by nasogastric tube divided into six equal feedings.

Later on, the child should be given cereal made with a greater amount of skimmed milk product and vegetable oil and slightly less sugar.

[22] The WHO recommends that all severely malnourished children admitted to hospital should receive broad-spectrum antibiotics (for example, gentamicin and ampicillin).

This can lead to life-threatening dehydration or electrolyte imbalances within hours when fluid loss is severe.

For each cycle of the transport, hundreds of water molecules move into the epithelial cell to maintain osmotic equilibrium.

[40] In the early 1980s, "oral rehydration therapy" meant only the preparation prescribed by the World Health Organization (WHO) and UNICEF.

[43] In 1953, Hemendra Nath Chatterjee published in The Lancet the results of using ORT to treat people with mild cholera.

[44][45] He did not publish any balance data, and his exclusion of patients with severe dehydration did not lead to any confirming study; his report remained anecdotal.

[citation needed] Robert Allan Phillips tried to make an effective ORT solution based on his discovery that, in the presence of glucose, sodium, and chloride could be absorbed in patients with cholera; but he failed because his solution was too hypertonic and he used it to try to stop the diarrhea rather than to rehydrate patients.

[citation needed] In the early 1960s, Robert K. Crane described the sodium-glucose co-transport mechanism and its role in intestinal glucose absorption.

In 1967–1968, Norbert Hirschhorn and Nathaniel F. Pierce showed that people with severe cholera can absorb glucose, salt, and water and that this can occur in sufficient amounts to maintain hydration.

Cash, helped by Rafiqul Islam and Majid Molla, reported that giving adults with cholera an oral glucose-electrolyte solution in volumes equal to those of the diarrhea losses reduced the need for IV fluid therapy by eighty percent.

When IV fluid ran out in the refugee camps, Dilip Mahalanabis, a physician working with the Johns Hopkins International Center for Medical Research and Training in Calcutta, issued instructions to prepare an oral rehydration solution and to distribute it to family members and caregivers.

[citation needed] In the 1970s, Norbert Hirschhorn used oral rehydration therapy on the White River Apache Indian Reservation with a grant from the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases.

[50][51][52] He observed that children voluntarily drank as much of the solution as needed to restore hydration, and that rehydration and early re-feeding would protect their nutrition.

[citation needed] In 1980, the Bangladeshi nonprofit BRAC created a door-to-door and person-to-person sales force to teach ORT for use by mothers at home.

Later on, the approach was broadcast over television and radio, and a market for oral rehydration salts packets developed.

Three decades later, national surveys have found that almost 90% of children with severe diarrhea in Bangladesh are given oral rehydration fluids at home or in a health facility.