Ordinal number

[1] A finite set can be enumerated by successively labeling each element with the least natural number that has not been previously used.

To extend this process to various infinite sets, ordinal numbers are defined more generally using linearly ordered greek letter variables that include the natural numbers and have the property that every set of ordinals has a least or "smallest" element (this is needed for giving a meaning to "the least unused element").

Although the distinction between ordinals and cardinals is not always apparent on finite sets (one can go from one to the other just by counting labels), they are very different in the infinite case, where different infinite ordinals can correspond to sets having the same cardinal.

Like other kinds of numbers, ordinals can be added, multiplied, and exponentiated, although none of these operations are commutative.

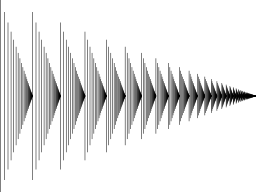

Further on, there will be ω3, then ω4, and so on, and ωω, then ωωω, then later ωωωω, and even later ε0 (epsilon nought) (to give a few examples of relatively small—countable—ordinals).

Given the axiom of dependent choice, this is equivalent to saying that the set is totally ordered and there is no infinite decreasing sequence (the latter being easier to visualize).

Such a one-to-one correspondence is called an order isomorphism, and the two well-ordered sets are said to be order-isomorphic or similar (with the understanding that this is an equivalence relation).

However, this definition still can be used in type theory and in Quine's axiomatic set theory New Foundations and related systems (where it affords a rather surprising alternative solution to the Burali-Forti paradox of the largest ordinal).

It can be shown by transfinite induction that every well-ordered set is order-isomorphic to exactly one of these ordinals, that is, there is an order preserving bijective function between them.

If it were a set, one could show that it was an ordinal and thus a member of itself, which would contradict its strict ordering by membership.

An ordinal is finite if and only if the opposite order is also well-ordered, which is the case if and only if each of its non-empty subsets has a greatest element.

Transfinite induction holds in any well-ordered set, but it is so important in relation to ordinals that it is worth restating here.

It then follows by transfinite induction that there is one and only one function satisfying the recursion formula up to and including α.

Now that F(0) is known, the definition applied to F(1) makes sense (it is the smallest ordinal not in the singleton set {F(0)} = {0}), and so on (the and so on is exactly transfinite induction).

Ordinal addition, multiplication and exponentiation are continuous as functions of their second argument (but can be defined non-recursively).

Any well-ordered set is similar (order-isomorphic) to a unique ordinal number

The technique of indexing classes of ordinals is often useful in the context of fixed points: for example, the

Each can be defined in essentially two different ways: either by constructing an explicit well-ordered set that represents the operation or by using transfinite recursion.

The Cantor normal form provides a standardized way of writing ordinals.

However, this cannot form the basis of a universal ordinal notation due to such self-referential representations as ε0 = ωε0.

Ordinals are a subclass of the class of surreal numbers, and the so-called "natural" arithmetical operations for surreal numbers are an alternative way to combine ordinals arithmetically.

The axiom of choice is equivalent to the statement that every set can be well-ordered, i.e. that every cardinal has an initial ordinal.

It may be clearer to apply Von Neumann cardinal assignment to finite cases and to use Scott's trick for sets which are infinite or do not admit well orderings.

Note that cardinal and ordinal arithmetic agree for finite numbers.

Notice that a number of authors define cofinality or use it only for limit ordinals.

As mentioned above (see Cantor normal form), the ordinal ε0 is the smallest satisfying the equation

The transfinite ordinal numbers, which first appeared in 1883,[8] originated in Cantor's work with derived sets.

Cantor called the set of finite ordinals the first number class.

Cantor's work with derived sets and ordinal numbers led to the Cantor-Bendixson theorem.

Therefore, the non-limit number classes partition the ordinals into pairwise disjoint sets.