Oregon Trail

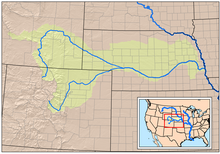

The first land route across the present-day contiguous United States was mapped by the Lewis and Clark Expedition between 1804 and 1806, following these 1803 instructions from President Thomas Jefferson to Meriwether Lewis: "The object of your mission is to explore the Missouri river, and such principal stream of it, as, by its course and communication with the waters of the Pacific Ocean, whether the Columbia, Oregon, Colorado and/or other river may offer the most direct and practicable water communication across this continent, for commerce.

"[2] Although Lewis and William Clark found a path to the Pacific Ocean, it was neither direct nor practicable for prairie schooner wagons to pass through without considerable road work.

Two movements of PFC employees were planned by Astor: one sent to the Columbia River aboard the merchant ship Tonquin, the other dispatched overland under an expedition led by Wilson Price Hunt.

Along the way, he camped at the confluence of the Columbia and Snake Rivers and posted a notice claiming the land for Britain and stating the intention of the North West Company to build a fort on the site.

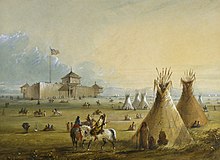

[citation needed] Although officially the HBC discouraged settlement because it interfered with its lucrative fur trade, its manager at Fort Vancouver, John McLoughlin, gave substantial help, including employment, until they could get established.

By 1825 the HBC started using two brigades, each setting out from opposite ends of the express route—one from Fort Vancouver on the Columbia River and the other from York Factory on Hudson Bay—in spring and passing each other in the middle of the continent.

Canada had few potential settlers who were willing to move more than 2,500 miles (4,000 km) to the Pacific Northwest, although several hundred ex-trappers, British and American, and their families did start settling in what became Oregon and Washington.

[13] Fur traders included Manuel Lisa, Robert Stuart, William Henry Ashley, Jedediah Smith, William Sublette, Andrew Henry, Thomas Fitzpatrick, Kit Carson, Jim Bridger, Peter Skene Ogden, David Thompson, James Douglas, Donald Mackenzie, Alexander Ross, James Sinclair, and other mountain men.

Trapper Jim Beckwourth described the scene as one of "Mirth, songs, dancing, shouting, trading, running, jumping, singing, racing, target-shooting, yarns, frolic, with all sorts of extravagances that white men or Indians could invent.

Other missionaries, mostly husband and wife teams using wagon and pack trains, established missions in the Willamette Valley, as well as various locations in the future states of Washington, Oregon, and Idaho.

On May 1, 1839, a group of eighteen men from Peoria, Illinois, set out with the intention of colonizing the Oregon country on behalf of the United States of America and driving out the HBC operating there.

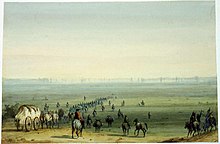

Jesse Applegate's account of the emigration, "A Day with the Cow Column in 1843," has been described as "the best bit of literature left to us by any participant in the [Oregon] pioneer movement..."[23] and has been republished several times from 1868 to 1990.

[26] However, feminist scholarship, by historians such as Lillian Schlissel,[27] Sandra Myres,[28] and Glenda Riley,[29] suggests men and women did not view the West and western migration in the same way.

[31]Similarly, emigrant Martha Gay Masterson, who traveled the trail with her family at the age of 13, mentioned the fascination she and other children felt for the graves and loose skulls they would find near their camps.

[34] Following persecution and mob action in Missouri, Illinois, and other states, and the assassination of their prophet Joseph Smith in 1844, Mormon leader Brigham Young led settlers in the Latter Day Saints (LDS) church west to the Salt Lake Valley in present-day Utah.

In 1847 Young led a small, fast-moving group from their Winter Quarters encampments near Omaha, Nebraska, and their approximately 50 temporary settlements on the Missouri River in Iowa including Council Bluffs.

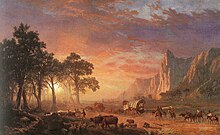

They initially started in 1848 with trains of several thousand emigrants, which were rapidly split into smaller groups to be more easily accommodated at the limited springs and acceptable camping places on the trail.

The "forty-niners" often chose speed over safety and opted to use shortcuts such as the Sublette-Greenwood Cutoff in Wyoming which reduced travel time by almost seven days but spanned nearly 45 miles (72 km) of the desert without water, grass, or fuel for fires.

[37] 1849 was the first year of large scale cholera epidemics in the United States, and thousands are thought to have died along the trail on their way to California—most buried in unmarked graves in Kansas and Nebraska.

Paddle wheel steamships and sailing ships, often heavily subsidized to carry the mail, provided rapid transport to and from the East Coast and New Orleans, Louisiana, to and from Panama to ports in California and Oregon.

Corps of Topographical Engineers led by Captain James H. Simpson left Camp Floyd, Utah, to establish an army supply route across the Great Basin to the eastern slope of the Sierras.

In 1860–1861, the Pony Express, employing riders traveling on horseback day and night with relay stations about every 10 miles (16 km) to supply fresh horses, was established from St. Joseph, Missouri, to Sacramento, California.

Contemporary interest in the overland trek has prompted the states and federal government to preserve landmarks on the trail including wagon ruts, buildings, and "registers" where emigrants carved their names.

[60] It was about 80 miles (130 km) shorter than the main trail through Fort Bridger with good grass, water, firewood, and fishing but it was a much steeper and rougher route, crossing three mountain ranges.

Another possible crossing was a few miles upstream of Salmon Falls where some intrepid travelers floated their wagons and swam their stock across to join the north side trail.

[87] In desperate times, migrants would search for less-popular sources of food, including coyote, fox, jackrabbit, marmot, prairie dog, and rattlesnake (nicknamed "bush fish" in the later period).

[88] Nevertheless, pioneers' consumption of the wild berries (including chokeberry, gooseberry, and serviceberry) and currants that grew along the trail (particularly along the Platte River) helped make scurvy infrequent.

[87][88] Marcy's guide correctly suggested that the consumption of wild grapes, greens, and onions could help prevent the disease and that if vegetables were not available, citric acid could be drunk with sugar and water.

Catching a fatal disease was a distinct possibility as Ulysses S. Grant in 1852 learned when his unit of about 600 soldiers and some of their dependents traversed the Isthmus and lost about 120 men, women, and children.

The ultimate competitor arrived in 1869, the first transcontinental railroad, which cut travel time to about seven days at a low fare of about $60 (economy)[118] One of the enduring legacies of the Oregon Trail is the expansion of the United States territory to the West Coast.