Snake River

Although travelers on the Oregon Trail initially shunned the dry and rocky Snake River region, a flood of settlers followed gold discoveries in the 1860s, leading to decades of military conflict and the eventual expulsion of tribes to reservations.

The Snake River starts to the north of Two Ocean Pass near the southern border of Yellowstone National Park, about 9,200 feet (2,800 m) above sea level in the Rocky Mountains of Wyoming.

About 30 percent of the watershed is farmland; irrigated farming of potatoes, sugar beets, onions, cereal grains and alfalfa are dominant in the Snake River Plain, while the Palouse Hills of the northwest host mainly dryland wheat and legume production.

[30]: 606 The forests contain numerous designated wilderness areas, including the Sawtooth, Selway–Bitterroot, Frank Church-River of No Return, Gospel Hump, Hells Canyon, Teton and Gros Ventre.

[75] From about 11–9 Ma, crustal deformation related to the Yellowstone hotspot caused the western half of the Snake River Plain to sink, creating a graben-type valley between parallel fault zones to the northeast and southwest.

Upwelling magma caused the continental crust to rise, forming highlands in a similar fashion to the modern Yellowstone plateau and leaving behind enormous basalt flows in its wake.

As the hotspot migrated east relative to the North American Plate, the land behind it collapsed and sank, creating the geographic depression of the eastern Snake River Plain.

[79] The migrating Continental Divide tilted the regional slope such that drainage flowed west into Lake Idaho, whose water levels saw a significant increase about 4.5 Ma.

During this expansion, the Snake also captured the Bear River, which was only rerouted towards its modern outlet in the Great Salt Lake Basin about 50,000 or 60,000 years ago by lava flows in southeast Idaho.

[73]: 222–223 About 2.5 Ma, Lake Idaho reached a maximum elevation of 3,600 feet (1,100 m) above modern sea level, and overflowed northward into the Salmon-Clearwater drainage near present-day Huntington, Oregon.

Over a period of about two million years, the outflow carved Hells Canyon, emptying Lake Idaho and integrating the upper Snake and Salmon-Clearwater into a single river system.

About 15,000 years ago the lip of Red Rock Pass south of present-day Pocatello, Idaho abruptly collapsed, releasing a tremendous volume of water from Lake Bonneville into the Snake River Plain.

[85][86] The floodwaters then emptied through Hells Canyon; however, most evidence of their effects on the lower Snake River was erased by the much larger Missoula Floods that engulfed the Columbia Basin during the same period.

[85] Caused by the repeated collapse of an ice dam in western Montana, dozens of floods overflowed into the lower Snake River from the north, backing water as far upstream as Lewiston.

[90] Starting about 2200 BCE, people in the western Snake River basin began to adopt a semi-sedentary lifestyle, with an increased reliance on fish (primarily salmon) and food preservation and storage.

[96]: 44 Downriver of Shoshone Falls, salmon and their cousins such as steelhead trout – anadromous fish which spend their adult lives in the ocean, returning to fresh water to spawn – were a key food source for indigenous peoples, and were of great cultural importance.

[103] With horses, the Nez Perce were able to travel east of the Bitterroot Mountains to hunt bison, via the trail over Lolo Pass, which the Lewis and Clark expedition would later follow in order to reach the Snake and Columbia Rivers.

He wrote that "the passage by water is now proved to be safe and practicable for loaded boats, without one single carrying place or portage; therefore, the doubtful question is set at rest forever.

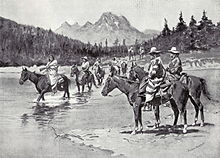

After a treacherous crossing of the Snake at Dug Bar, Hells Canyon on May 31,[124] the Nez Perce were pursued by the Army for over 1,000 miles (1,600 km) east, through Yellowstone before turning north through Montana, fighting several battles along the way.

In 1865, Thomas Stump attempted to pilot the Colonel Wright up Hells Canyon, making it 80 miles (130 km) upriver before hitting rocks in a rapid, forcing their retreat.

[137] The Idaho State Historical Society writes that "Perrine’s venture contrasted remarkably with private canal company failures that led to congressional provision for federal reclamation projects after 1902.

As a rare successful example of state supervised private irrigation development provided for in [the Carey Act] of 1894, Milner Dam and its canal system have national significance in agricultural history.

[138] Starting with Minidoka Dam in 1906, the project would grow over the next few decades to include major reservoirs at Jackson Lake, American Falls and Island Park, and a large network of canals and pump stations.

While that location offered greater power potential, the fishery supported by the Salmon River was considered too economically valuable to wipe out, and in 1964 the Commission chose to authorize the High Mountain Sheep project.

[152][151] By then, significant public opposition had formed against the high dam, as it would still block salmon migration to the upper Snake, and adversely affect wildlife and recreational values in Hells Canyon.

By 1966 it reached an agreement with the Federal Power Commission to move forward with the hatchery plan, and by 1967 both Oxbow and Hells Canyon dams had been completed, neither with provision for fish passage.

[120]: 100–103 While opponents continued to stall the project for a few more years, Washington Senator Warren G. Magnuson pushed through a budget amendment in 1955 to start construction on the first dam, Ice Harbor.

[30]: 608 Anadromous salmonids (Oncorhynchus), including chinook, coho, and sockeye salmon, and redband and steelhead trout, were historically the most abundant fish and a keystone species of the Snake River system.

About two-thirds of the Snake River Plain remains grassland or shrubland; however, much of this acreage is impacted by livestock grazing, and fire regimes have become more severe with the proliferation of invasive species like cheatgrass.

[174] In the context of shipping, while river traffic has declined in recent years, it remains important to the area's economy, and moving cargo by barge is cheaper and twice as fuel-efficient as diesel trains.