History of the Quran

In Sunni tradition, it is believed that the first caliph Abu Bakr ordered Zayd ibn Thabit to compile the written Quran, relying upon both textual fragments and the memories of those who had memorized it during Muhammad's lifetime,[2] with the rasm (undotted Arabic text) being officially canonized under the third caliph Uthman ibn Affan (r. 644–656 CE),[3] leading the Quran as it exists today to be known as the Uthmanic codex.

[4] Some Shia Muslims believe that the fourth caliph Ali ibn Abi Talib was the first to compile the Quran shortly after Muhammad died.

[10][11] German palaeographer Gerd R. Puin, professor of Arabic language and literature at Saarland University in Saarbrücken, affirms that these variants indicate an evolving text as opposed to a fixed one.

For example, sources based on some archaeological data give the construction date of Masjid al-Haram, an architectural work mentioned 16 times in the Quran, as 78 AH[13] an additional finding that sheds light on the evolutionary history of the Quranic texts mentioned,[12] which is known to continue even during the time of Hajjaj,[14][15] in a similar situation that can be seen with al-Aksa, though different suggestions have been put forward to explain.

[Note 1] A similar situation can be put forward for Mecca, which was not recorded as a pilgrimage center in any historical source before 741 and lacks pre-Islamic archaeological data.

[21][Note 2] While there are various proposed etymologies, one is that the word 'Quran' (قرآن) comes from the Arabic verb qaraʾa (قرء, 'to read') in the verbal noun pattern fuʿlān (فعلان), thus resulting in the meaning 'reading'.

According to Islamic belief, the revelations started one night during the month of Ramadan in 610 CE, when Muhammad, at the age of forty, received the first visit from the angel Gabriel,[24] reciting to him the first verses of Surah Al-Alaq.

"[34] Some scholars argue that this provides evidence that the Quran had been collected and written during this time because it is not correct to call something al-kitab (book) when it is merely in the [people's] memories.

He further considers the role of writing among Arabs in the early seventh century and accounts in the Sira of the dictation of parts of the Quran to scribes towards the end of the Medinan period.

Consequently, upon Umar's insistence, Abu Bakr ordered the collection of the hitherto scattered pieces of the Quran into one copy,[43][44] assigning Zayd ibn Thabit, Muhammad's main scribe, to gather the written fragments held by different members of the community.

Ibn Thabit noted: "So I started looking for the Holy quran and collected it from (what was written on) palm-leaf stalks, thin white stones, and also from men who knew it by heart, until I found the last verse of Surat at-Tauba (repentance) with Abi Khuzaima al-Ansari, and I did not find it with anybody other than him.

[40] According to Islamic tradition, the process of canonization ended under the third caliph, Uthman ibn Affan (r. 23/644–35/655), about twenty years after the death of Muhammad in 650 CE, though the date is not exact because it was not recorded by early Arab annalists.

The Caliphate had grown considerably, expanding into Iraq, Syria, Egypt, and Iran, bringing into Islam's fold many new converts from various cultures with varying degrees of isolation.

[64][65][66] In Twelver belief, the codex is now in the possession of their last Imam, Muhammad al-Mahdi,[67] who is hidden from the public by divine will since 874, until his reappearance at the end of time to eradicate injustice and evil.

[72][65][73] Among others, such reports can be found in Kitab al-Qira'at by the ninth-century Shia exegete Ahmad ibn Muhammad al-Sayyari,[69][74] though he has been widely accused of connections to the Ghulat (lit.

[100] Many historians, including Emran El-Badawi and Fred Donner, have written rejoinders to arguments from the revisionist school and in favor of a canonization date in the time of Uthman.

[102][103] Although few, some seventh-century material evidence exists for the Quran, primarily from coins and commemorative inscriptions (Dome of the Rock) dating to the reign of Abd al-Malik ibn Marwan (685–705) especially containing the Basmala, the Shahada, and Surat al-Ikhlas (Q 112).

[106] It is typically accepted nowadays, including among skeptical scholars like Patricia Crone and Stephen Shoemaker, that the majority of the Quran at the least goes back in some fashion to Muhammad.

With the discovery of earlier manuscripts which conform to the Uthmanic standard, the revisionist view fell out of favor and has been described as "untenable",[108] with western scholarship generally supporting the traditional date.

Professor Sean Anthony has discussed the textual history of these two surahs in detail and noted that their presence in mushafs modelled after Ubayy's (and to a lesser extent, certain other companions) is "robustly represented in our earliest and best sources".

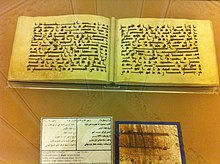

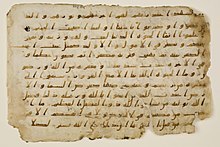

The surah order of the lower text of the early seventh century Ṣanʽā’ 1 palimpsest is known to have similarities with that reported of Ubayy (and to a lesser extent, that of Ibn Mas'ud).

Early Quranic Arabic was written in a rasm which lacked precision because distinguishing between consonants was impossible due to the absence of diacritical marks (a'jam).

[122] Under Abd al-Malik's reign, Abu'l Aswad al-Du'ali (died 688) founded the Arabic grammar and invented the system of placing large coloured dots to indicate the tashkil.

The slanted isolated form of the alif that was present in the Umayyad period completely disappeared and was replaced by a straight shaft with a pronounced right-sided foot, set at a considerable distance from the following letter.

His system has been universally used since the early 11th century, and includes six diacritical marks: fatha (a), damma (u), kasra (i), sukun (vowel-less), shadda (double consonant), madda (vowel prolongation; applied to the alif).

Economic factors may also have played a part because while the "new style" was being introduced, paper was also beginning to spread throughout the Muslim world, and the decrease in the price of books triggered by the introduction of this new material seems to have led to an increase in its demand.

[134] A committee of leading professors from Al-Azhar University[135] had started work on the project in 1907 but it was not until 10 July 1924 that the "Cairo Qur’an" was first published by Amiri Press under the patronage of Fuad I of Egypt,[136][137] as such, it is sometimes known as the "royal (amīriyya) edition.

"[138] The goal of the government of the newly formed Kingdom of Egypt was not to delegitimize the other qir’at, but to eliminate that, which the colophon labels as errors, found in Qur’anic texts used in state schools.

Some Shias questioned the integrity of the Uthmanic codex, stating that two surahs, "al-Nurayn" (The Two Lights) and "al-Walayah" (the Guardianship), which dealt with the virtues of Muhammad's family, were removed.

He states that the collection of the Quran by Abu Bakr, Umar, and Uthman occurred significantly after the caliphate was decided, and so if Ali's rule had been mentioned, there would have been no need for the Muslims to gather to appoint someone.