Khalili Collection of Islamic Art

[7][8][9] In addition to copies of the Quran, and rare and illustrated manuscripts, the collection includes album and miniature paintings, lacquer, ceramics, glass and rock crystal, metalwork, arms and armour, jewellery, carpets and textiles, over 15,000 coins, and architectural elements.

Around 200 objects relate to medieval Islamic science and medicine, including astronomical instruments for orienting towards Mecca, tools, scales, weights, and "magic bowls" intended for medical use.

[5] Based in the UK and originally from Iran, Nasser David Khalili has assembled eight distinct art collections, each considered among the most important in its field.

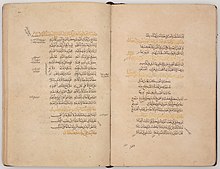

[29] An exceptionally large single-volume Quran dated to 1552 AD was in the Mughal imperial library during the reigns of Aurangzeb and Shah 'Alam, bearing their seals.

[30] An 18th-century single-volume Quran, the work of calligrapher Mahmud Celaleddin Efendi, was previously owned by Ottoman princess Nazime Sultan.

There are several complete exemplars or folios of the Shahnameh (Book of Kings), the national epic poem of Iran, whose text and illustrations combine historical and mythical material.

[36] Among many detached folios from Iran, especially 17th-century Isfahan, are works by Reza Abbasi, Mo'en Mosavver, Mohammad Zaman, Aliquli Jabbadar, and Shaykh 'Abbasi.

[37] The folios from 15th-century Ottoman Turkey include two from a Siyer-i Nebi (a biography of Prophet Muhammed) commissioned by Sultan Murad III.

[36] Some folios are from works of dynastic or global history, including two from the earliest surviving illustrated exemplar of the Zafarnama by Sharaf ad-Din Ali Yazdi, from 1436 AD.

[39] A painting from the Padshanamah (chronicle of the king's reign) shows Shah Jahan, with family and courtiers, watching two elephants fighting.

[41] Other manuscripts include a lavishly illuminated exemplar of part one of Al-Shifa bi Ta'rif Huquq al-Mustafa (a detailed commentary on the life and character of Muhammed) from the 17th-century Moroccan royal court.

[52] A brass casket from early 13th-century Jazira, lavishly inlaid with silver, has four numeric dials; these formed part of a combination lock whose mechanism is now missing.

[53] The jewellery in the collection numbers almost 600 personal adornments,[54] plus more than 600 rings[55] and 200 luxury items from the royal workshops of the Mughal Empire.

[57] Most of the enamelled gold objects made for the Mughal court are now in the Iranian crown jewels or in the Hermitage Museum in Russia; an exception is an octagonal box in the Khalili collection that dates from around 1700.

[66] Describing the arms and armour catalogue, James W. Allan, Professor of Eastern Art at the University of Oxford, wrote "The range of pieces [...] is quite extraordinary: a 1.8 m long seventeenth-century Indian cannon, Turkish and Persian daggers with astonishingly beautiful enamelled handles and scabbards, gold fittings for a 10th-century Chinese saddle, a Moroccan horse-shoe etc.

[72] Some of the collection's textiles have explicitly religious purposes: a North African silk panel repeats the name of Allah hundreds of times and a carpet was used as a mihrab (prayer niche).

[76] A 19th-century pen box, 30 centimetres (12 in) long, was commissioned by Mohammad Shah Qajar for his official Manouchehr Khan Gorji, commemorating the latter's battle against Bedouins.

[78] Ceramic styles popular in the Islamic world include lustreware (with a thin metallic film), sgraffiato (in which the design is etched into the slip), and underglaze pottery.

[79] Khalili's ceramic collection, numbering nearly 2,000 items, has been described as particularly strong in pottery of the Timurid era and also that of pre-Mongol Bamiyan.

[81] Other unique items include a bowl with a depiction of a Buraq, a four-legged creature that is said to have borne Muhammad from Mecca to Jerusalem and then to heaven.

[85] Egyptian and Syrian glassmakers of the 13th and 14th centuries made lavishly decorated enamelled and gilded glassware which was in demand for export, and the collection's objects cover this period.

Some of these were commissioned by the Mamluk Court for mosques, and the collection includes one created for the 14th-century Sultan Barquq,[86] decorated with his heraldic roundel.

[85] The collection's 15,000 gold, silver, and copper coins come from the entire Islamic world and span the time period from 700 to 2000 AD.

[90] Throughout the history of Islam, its rituals have made use of scientific procedures to find the direction of Mecca and to determine the times of prayers within the lunar calendar.

[91] Around two hundred objects in the collection relate to medieval Islamic science and medicine, including astronomical instruments, tools, scales, weights, and supposedly magical items intended for medical use.

[98] The tombstones are of varying origins and materials, including a carved and calligraphed stele, nearly two metres (6 ft 7 in) high, from Northern India.

[98] A carved wooden cenotaph, dated 1496–7 AD, from a shrine in the Caspian area of Iran bears the craftsman's signature and the names of donors.

[98] This collection was the basis in 2008 for the first comprehensive exhibition of Islamic art to be staged in the Middle East, at the Emirates Palace in Abu Dhabi.

[106] A review said that each volume "has been produced to a standard that is seldom seen in this small corner of the art world [...] backed up by solid scholarship from respected authorities".

An astrolabe and a statuette of a camel and rider from the Khalili Collection of Islamic Art were among the objects used to illustrate the game's setting of 9th century Baghdad.