Origin of Hangul

It was created in the mid fifteenth century by King Sejong,[1][2] as both a complement and an alternative to the logographic Sino-Korean Hanja.

Initially denounced by the educated class as eonmun (vernacular writing; 언문, 諺文), it only became the primary Korean script following independence from Japan in the mid-20th century.

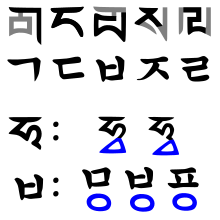

However, the suprasegmental features of tone and vowel length, seen as single and double tick marks to the left of the syllabic blocks in the image in the next section, have been dropped.

It faced heavy opposition from Confucian scholars educated in Chinese, notably Choe Manri, who believed hanja to be the only legitimate writing system.

[citation needed] The account of the design of the Korean alphabet was lost, and it would not return to common use until after World War II.

[citation needed] Following the Indic tradition, consonants in the Korean alphabet are classified according to the speech organs involved in their production.

There were a few additional irregular consonants, such as the coronal lateral/flap ㄹ [l~ɾ], which the Haerye only explains as an altered outline of the tongue, and the velar nasal ㆁ [ŋ].

The irregularity of the labials has no explanation in the Haerye, but may be a remnant of the graphic origin of the basic letter shapes in the imperial ʼPhags-pa alphabet of Yuan Dynasty China.

[13] Iotation was then indicated by doubling this dot: ㅕ yə, ㅑ ya, ㅠ yu, ㅛ yo.

The horizontal letters ㅡㅜㅗ ɨ u o represented back vowels *[ɯ], *[u], *[o] in the fifteenth century, as they do today, whereas the fifteenth-century sound values of ㅣㅓㅏ i ə a are uncertain.

Nothing would disturb me more, after this study is published, than to discover in a work on the history of writing a statement like the following: "According to recent investigations, the Korean alphabet was derived from the Mongol's phags-pa script.

Indeed, records from Sejong's day played with this ambiguity, joking that "no one is older (more 古 gǔ) than the 蒙古 Měng-gǔ".

[citation needed] There were ʼPhags-pa manuscripts in the Korean palace library from the Yuan Dynasty government, including some in the seal-script form, and several of Sejong's ministers knew the script well.

[citation needed] It is postulated that the Koreans adopted five core consonant letters from ʼPhags-pa, namely ㄱ g [k], ㄷ d [t], ㅂ b [p], ㅈ j [ts], and ㄹ l [l].

These were the consonants basic to Chinese phonology, rather than the graphically simplest letters (ㄱ g [k], ㄴ n [n], ㅁ m [m], and ㅅ s [s]) taken as the starting point by the Haerye.

[20] For example, the box inside ʼPhags-pa ꡂ g [k] is not found in the Korean ㄱ g [k]; only the outer stroke remains.

However, Ledyard's explanation[citation needed] of the letter ㆁ ng [ŋ] differs from the Haerye account; he sees it as a fusion of velar ㄱ g and null ㅇ, reflecting its variable pronunciation.

Sejong's solution solved both problems: The vertical stroke left from ㄱ g was added to the null symbol ㅇ to create ㆁ ng,[21] iconically capturing both regional pronunciations as well as being easily legible.

Eventually the graphic distinction between the two silent initials ㅇ and ㆁ was lost, as they never contrasted in Korean words.

Another letter composed of two elements to represent two regional pronunciations, now obsolete, was ㅱ, which transcribed the Chinese initial 微.

), while in hangul, which does not have an h among its basic consonants, they are based on the labial series ㅁ m, ㅂ b, ㅍ p. An additional letter, the 'semi-sibilant' ㅿ z, now obsolete, has no explanation in either Ledyard or the Haerye.

It also had two pronunciations in Chinese, as a sibilant and as a nasal (approximately [ʑ] and [ɲ]) and so, like ㅱ for [w] ~ [m] and ㆁ for ∅ ~ [ŋ], may have been a composite of existing letters.